Robbie Jack/Corbis via Getty Images

Cora Fox, Arizona State University

What is “happiness” – and who gets to be happy?

Since 2012, the World Happiness Report has measured and compared data from 167 countries. The United States currently ranks 24th, between the U.K. and Belize – its lowest position since the report was first issued. But the 2025 edition – released on March 20, the United Nations’ annual “International Day of Happiness” – starts off not with numbers, but with Shakespeare.

“In this year’s issue, we focus on the impact of caring and sharing on people’s happiness,” the authors explain. “Like ‘mercy’ in Shakespeare’s ‘Merchant of Venice,’ caring is ‘twice-blessed’ – it blesses those who give and those who receive.”

Shakespeare’s plays offer many reflections on happiness itself. They are a record of how people in early modern England experienced and thought about joy and satisfaction, and they offer a complex look at just how happiness, like mercy, lives in relationships and the caring exchanges between people.

Contrary to how we might think about happiness in our everyday lives, it is more than the surge of positive feelings after a great meal, or a workout, or even a great date. The experience of emotions is grounded in both the body and the mind, influenced by human physiology and culture in ways that change depending on time and place. What makes a person happy, therefore, depends on who that person is, as well as where and when they belong – or don’t belong.

Happiness has a history. I study emotions and early modern literature, so I spend a lot of my time thinking about what Shakespeare has to say about what makes people happy, in his own time and in our own. And also, of course, what makes people unhappy.

From fortune to joy

Tony Hisgett/Flickr via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

“Happiness” derives from the Old Norse word “hap,” which meant “fortune” or “luck,” as historians Phil Withington and Darrin McMahon explain. This earlier sense is found throughout Shakespeare’s works. Today, it survives in the modern word “happenstance” and the expression that something is a “happy accident.”

But in modern English usage, “happy” as “fortunate” has been almost entirely replaced by a notion of happiness as “joy,” or the more long-term sense of life satisfaction called “well-being.” The term “well-being,” in fact, was introduced into English from the Italian “benessere” around the time of Shakespeare’s birth.

The word and the concept of happiness were transforming during Shakespeare’s lifetime, and his use of the word in his plays mingles both senses: “fortunate” and “joyful.” That transitional ambiguity emphasizes happiness’ origins in ideas about luck and fate, and it reminds readers and playgoers that happiness is a contingent, fragile thing – something not just individuals, but societies need to carefully cultivate and support.

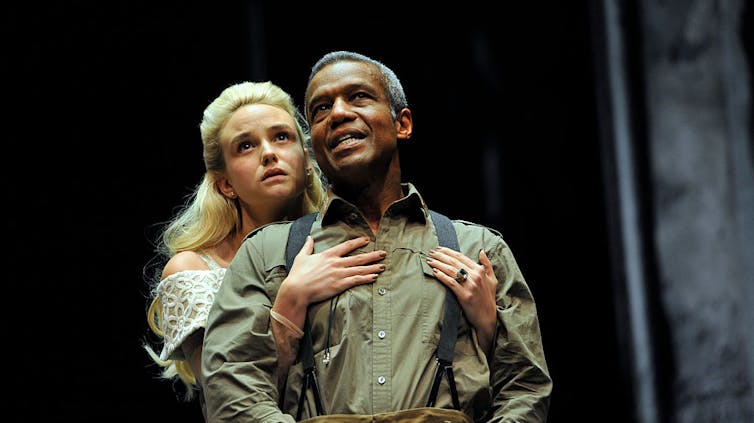

For instance, early in “Othello,” the Venetian senator Brabantio describes his daughter Desdemona as “tender, fair, and happy / So opposite to marriage that she shunned / The wealthy, curled darlings of our nation.” Before she elopes with Othello she is “happy” in the sense of “fortunate,” due to her privileged position on the marriage market.

Later in the same play, though, Othello reunites with his new wife in Cyprus and describes his feelings of joy using this same term:

…If it were now to die,

‘Twere now to be most happy, for I fear

My soul hath her content so absolute

That not another comfort like to this

Succeeds in unknown fate.

Desdemona responds,

The heavens forbid

But that our loves and comforts should increase

Even as our days do grow!

They both understand “happy” to mean not just lucky, but “content” and “comfortable,” a more modern understanding. But they also recognize that their comforts depend on “the heavens,” and that happiness is enabled by being fortunate.

“Othello” is a tragedy, so in the end, the couple will not prove “happy” in either sense. The foreign general is tricked into believing his young wife has been unfaithful. He murders her, then takes his own life.

The seeds of jealousy are planted and expertly exploited by Othello’s subordinate, Iago, who catalyzes the racial prejudice and misogyny underlying Venetian values to enact his sinister and cruel revenge.

Kathleen Ballard/Los Angeles Times/UCLA Library via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

Happy insiders and outsiders

“Othello” sheds light on happiness’s history – but also on its politics.

While happiness is often upheld as a common good, it is also dependent on cultural forces that make it harder for some individuals to experience. Shared cultural fantasies about happiness tend to create what theorist Sara Ahmed calls “affect aliens”: individuals who, by nature of who they are and how they are treated, experience a disconnect between what their culture conditions them to think should make them happy and their disappointment or exclusion from those positive feelings. Othello, for example, rightly worries that he is somehow foreign to the domestic happiness Desdemona describes, excluded from the joy of Venetian marriage. It turns out he is right.

Because Othello is foreign and Black and Desdemona is Venetian and white, their marriage does not conform to their society’s expectations for happiness, and that makes them vulnerable to Iago’s deceit.

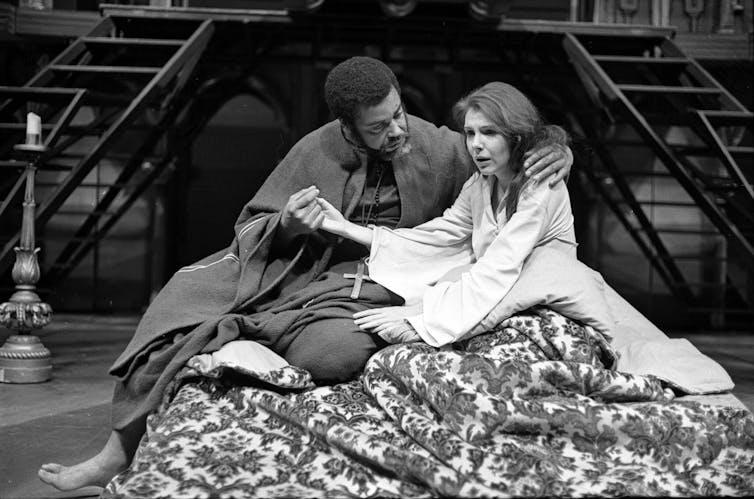

Similarly, “The Merchant of Venice” examines the potential for happiness to include or exclude, to build or break communities. Take the quote about mercy that opens the World Happiness Report.

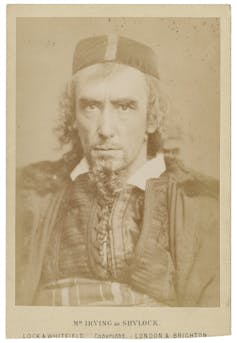

The phrase appears in a famous courtroom scene, as Portia attempts to persuade a Jewish lender, Shylock, to take pity on Antonio, a Christian man who cannot pay his debts. In their contract, Shylock has stipulated that if Antonio defaults on the loan, the fee will be a “pound of flesh.”

“The quality of mercy is not strained,” Portia lectures him; it is “twice-blessed,” benefiting both giver and receiver.

It’s a powerful attempt to save Antonio’s life. But it is also hypocritical: Those cultural norms of caring and mercy seem to apply only to other Christians in the play, and not the Jewish people living alongside them in Venice. In that same scene, Shylock reminds his audience that Antonio and the other Venetians in the room have spit on him and called him a dog. He famously asks why Jewish Venetians are not treated as equal human beings: “If you prick us, do we not bleed?”

Lock & Whitfield/Folger Shakespeare Library via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

Shakespeare’s plays repeatedly make the point that the unjust distribution of rights and care among various social groups – Christians and Jews, men and women, citizens and foreigners – challenges the happy effects of benevolence.

Those social factors are sometimes overlooked in cultures like the U.S., where contemporary notions of happiness are marketed by wellness gurus, influencers and cosmetic companies. Shakespeare’s plays reveal both how happiness is built through communities of care and how it can be weaponized to destroy individuals and the fabric of the community.

There are obvious victims of prejudice and abuse in Shakespeare’s plays, but he does not just emphasize their individual tragedies. Instead, the plays record how certain values that promote inequality poison relationships that could otherwise support happy networks of family and friends.

Systems of support

Pretty much all objective research points to the fact that long-term happiness depends on community, connections and social support: having systems in place to weather what life throws at us.

And according to both the World Happiness Report and Shakespeare, contentment isn’t just about the actual support you receive but your expectations about people’s willingness to help you. Societies with high levels of trust, like Finland and the Netherlands, tend to be happier – and to have more evenly distributed levels of happiness in their populations.

Shakespeare’s plays offer blueprints for trust in happy communities. They also offer warnings about the costs of cultural fantasies about happiness that make it more possible for some, but not for all.![]()

Cora Fox, Associate Professor of English and Health Humanities, Arizona State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.