STM Blog

Pharaohs in Dixieland – how 19th-century America reimagined Egypt to justify racism and slavery

Pharaohs in Dixieland – how 19th-century America reimagined Egypt to justify racism and slavery

Charles Vanthournout, Université de Lorraine

When Napoleon embarked upon a military expedition into Egypt in 1798, he brought with him a team of scholars, scientists and artists. Together, they produced the monumental “Description de l’Égypte,” a massive, multivolume work about Egyptian geography, history and culture.

At the time, the United States was a young nation with big aspirations, and Americans often viewed their country as an heir to the great civilizations of the past. The tales of ancient Egypt that emerged from Napoleon’s travels became a source of fascination to Americans, though in different ways.

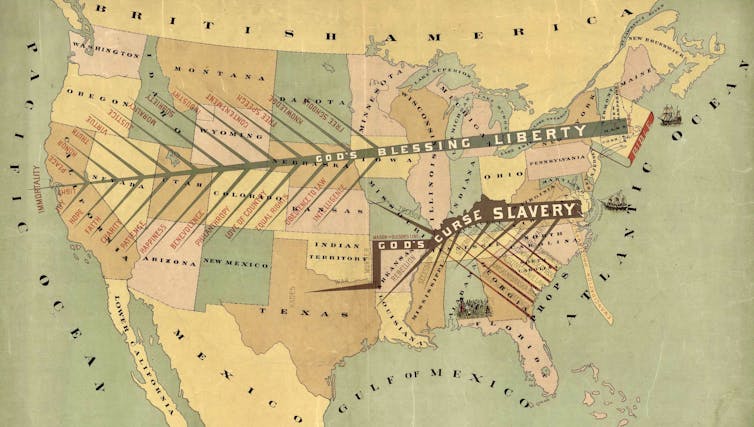

In the slaveholding South, ancient Egypt and its pharaohs became a way to justify slavery. For abolitionists and African Americans, biblical Egypt served as a symbol of bondage and liberation.

As a historian, I study how 19th-century Americans – from Southern intellectuals to Black abolitionists – used ancient Egypt to debate questions of race, civilization and national identity. My research traces how a distorted image of ancient Egypt shaped competing visions of freedom and hierarchy in a deeply divided nation.

Egypt inspires the pro-slavery South

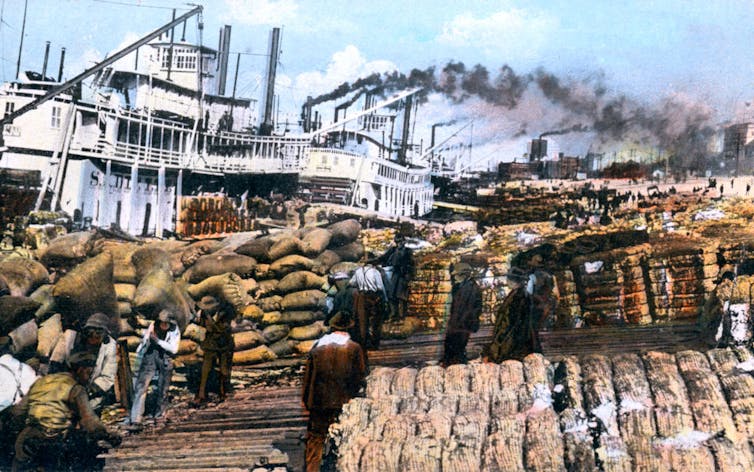

In 1819, when lawyer John Overton, military officer James Winchester and future president Andrew Jackson founded a city in Tennessee along the Mississippi River, they christened it Memphis, after the ancient Egyptian capital.

While promoting the new city, Overton declared of the Mississippi River that ran alongside it: “This noble river may, with propriety, be denominated the American Nile.”

“Who can tell that she may not, in time, rival … her ancient namesake, of Egypt in classic elegance and art?” The Arkansas Banner excitedly reported.

In the region’s fertile soil, Chancellor William Harper, a jurist and pro-slavery theorist from South Carolina, saw the promise of an agricultural empire built on slavery, one “capable of being made a far greater Egypt.”

There was a reason pro-slavery businessmen and thinkers were energized by the prospect of an American Egypt: Many Southern planters imagined themselves as guardians of a hierarchical and aristocratic system, one grounded in landownership, tradition and honor. As Alabama newspaper editor William Falconer put it, he and his fellow white Southerners belonged to a “race that had established law, order, and government on earth.”

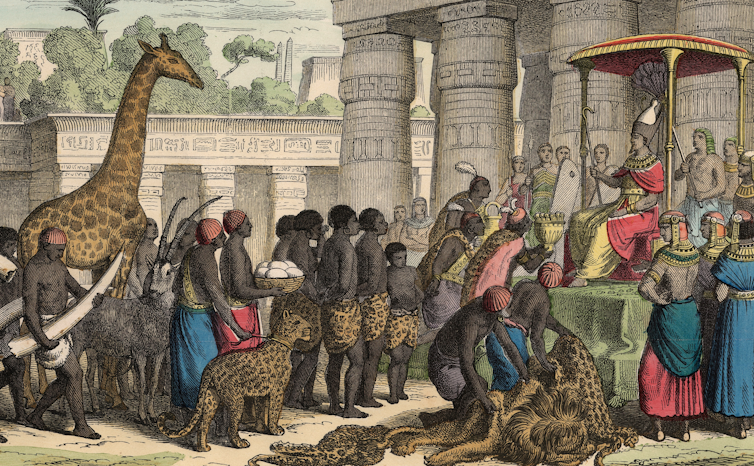

To them, Egypt represented the archetype of a great hierarchical civilization. Older than Athens or Rome, Egypt conferred a special legitimacy. And just like the pharaohs, the white elites of the South saw themselves as the stewards of a prosperous society sustained by enslaved labor.

The founders of Memphis named it after the ancient Egyptian capital, and they hoped the Mississippi River that ran alongside it would become an ‘American Nile.’ The Print Collector/Getty Images

Leading pro-slavery thinkers like Virginia social theorist George Fitzhugh, South Carolina lawyer and U.S. Senator Robert Barnwell Rhett and Georgia lawyer and politician Thomas R.R. Cobb all invoked Egypt as an example to follow.

“These [Egyptian] monuments show negro slaves in Egypt at least 1,600 years before Christ,” Cobb wrote in 1858. “That they were the same happy negroes of this day is proven by their being represented in a dance 1,300 years before Christ.”

A distorted view of history

But their view of history didn’t exactly square with reality. Slavery did exist in ancient Egypt, but most slaves had been originally captured as prisoners of war.

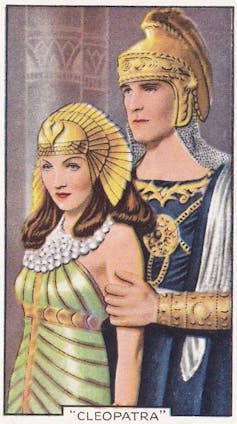

The country never developed a system of slavery comparable to that of Greece or Rome, and servitude was neither race-based nor tied to a plantation economy. The mistaken notion that Egypt’s great monuments were built by slaves largely stems from ancient authors and the biblical account of the Hebrews. Later, popular culture – especially Hollywood epics – would continue to advance this misconception.

Nonetheless, 19th-century Southern intellectuals drew on this imagined Egypt to legitimize slavery as an ancient and divinely sanctioned institution.

Even after the Civil War, which ended in 1865, nostalgia for these myths of ancient Egypt endured. In 1877, former Confederate officer Edward Fontaine noted how “Veritable specimens of black, woolyheaded negroes are represented by the old Egyptian artists in chains, as slaves, and even singing and dancing, as we have seen them on Southern plantations in the present century.”

Turning Egypt white

But to claim their place among the world’s great civilizations, Southerners had to reconcile a troubling fact: Egypt was located in Africa, the ancestral land of those enslaved in the U.S.

In response, an intellectual movement called the American School of Ethnology – which promoted the idea that races had separate, unequal origins to justify Black inferiority and slavery – set out to “whiten” Egypt.

In a series of texts and lectures, they portrayed Egypt as a slaveholding civilization dominated by whites. They pointed to Egyptian monuments as proof of the greatness that a slave society could achieve. And they also promoted a scientifically discredited theory called “polygenesis,” which argued that Black people did not descend from the Bible’s Adam, but from some other source.

Richard Colfax, the author of the 1833 pamphlet “Evidence Against the Views of the Abolitionists,” insisted that “the Egyptians were decidedly of the Caucasian variety of men.” Most mummies, he added, “bear not the most distant resemblance to the negro race.”

Physician Samuel George Morton cited “Crania Aegyptiaca,” an 1822 German study of Egyptian skulls, to reinforce this view. Writing in the Charleston Medical Journal in 1851, he explained how the German study had concluded that the skulls mirrored those of Europeans in size and shape. In doing so, it established “the negro his true position as an inferior race.”

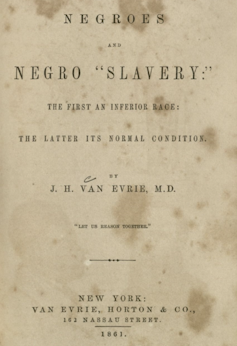

Physician Josiah C. Nott, Egyptologist George Gliddon and physician and propagandist John H. Van Evrie formed an effective triumvirate: Through press releases and public lectures featuring the skulls of mummies, they turned Egyptology into a tool of pro-slavery propaganda.

“The Negro question was the one I wished to bring out,” Nott wrote, adding that he “embalmed it in Egyptian ethnography.”

Nott and Gliddon’s 1854 bestseller “Types of Mankind” fused pseudoscience with Egyptology to both “prove” Black inferiority and advance the idea that their beloved African civilization was populated by a white Egyptian elite.

“Negroes were numerous in Egypt,” they write, “but their social position in ancient times was the same that it now is, that of servants and slaves.”

Denouncing America’s pharaohs

This distorted vision of Egypt, however, wasn’t the only one to take hold in the U.S., and abolitionists saw this history through a decidedly different lens.

In the Bible, Egypt occupies a central place, mentioned repeatedly as a land of refuge – notably for Joseph – but also as a nation of idolatry and as the cradle of slavery.

The episode of the Exodus is perhaps the most famous reference. The Hebrews, enslaved under an oppressive pharaoh, are freed by Moses, who leads them to the Promised Land, Canaan. This biblical image of Egypt as a land of bondage deeply shaped 19th-century moral and political debates: For many abolitionists, it represented the ultimate symbol of tyranny and human oppression.

When the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect on Jan. 1, 1863, Black people could be heard singing in front of the White House, “Go down Moses, way down in Egypt Land … Tell Jeff Davis to let my people go.”

Black Americans seized upon this biblical parallel. Confederate President Jefferson Davis was a contemporary pharaoh, with Moses still the prophet of liberation.

African American writers and activists like Phillis Wheatley and Sojourner Truth also invoked Egypt as a tool of emancipation.

“God has implanted in every human heart a principle which we call the love of liberty,” Wheatley wrote in a 1774 letter. “It is impatient with oppression and longs for deliverance; and with the permission of our modern Egyptians, I will assert that this same principle lives in us.”

Yet the South’s infatuation with Egypt shows how antiquity can always be recast to serve the powerful. And it’s a reminder that the past is far from neutral terrain – that there is rarely, if ever, a ceasefire in wars over history and memory.

Charles Vanthournout, Ph.D. Student in Ancient History, Université de Lorraine

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

STM Daily News is a multifaceted podcast that explores a wide range of topics, from life and consumer issues to the latest in food and beverage trends. Our discussions dive into the realms of science, covering everything from space and Earth to nature, artificial intelligence, and astronomy. We also celebrate the amateur sports scene, highlighting local athletes and events, including our special segment on senior Pickleball, where we report on the latest happenings in this exciting community. With our diverse content, STM Daily News aims to inform, entertain, and engage listeners, providing a comprehensive look at the issues that matter most in our daily lives. https://stories-this-moment.castos.com/

https://stmdailynews.com/%f0%9f%93%9c-who-created-blogging-a-look-back-at-the-birth-of-the-blog/

Discover more from Daily News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Knowledge

How Water Towers Work: The Simple System That Keeps Water Flowing in American Cities

Learn how water towers work in the United States, why they are so tall, and how gravity helps cities maintain water pressure and emergency water supplies.

How Water Towers Work

Water towers are one of the most recognizable pieces of infrastructure across the United States. Rising above towns, suburbs, and cities, these elevated tanks quietly perform a vital function every day: maintaining water pressure and storing emergency water for local communities.

Although they may look simple, water towers are an essential part of modern municipal water systems and remain one of the most reliable ways to deliver water to homes and businesses.

The Basic Science Behind Water Towers

Water towers work using a simple principle of physics: gravity.

Water from treatment plants or underground wells is pumped into a storage tank located high above the ground—typically between 100 and 200 feet tall. Because the tank is elevated, gravity naturally pushes the water downward through the city’s pipeline network.

This gravitational force creates the water pressure needed to supply homes, businesses, irrigation systems, and fire hydrants throughout the community.

Most residential plumbing systems in the United States operate best at 40 to 60 PSI (pounds per square inch), which water towers can easily provide through elevation alone.

Why Water Towers Are Built So Tall

The height of a water tower determines how much pressure it can create. Engineers use a common rule:

For example, a water tower standing 120 feet tall can generate roughly 50 PSI of pressure—perfect for delivering water throughout a residential neighborhood.

Why Cities Still Use Water Towers

While modern pumping systems could theoretically move water through pipes continuously, water towers provide several major advantages that make them a preferred design in many municipal systems.

- Stable Water Pressure – Water towers maintain consistent pressure even during peak usage times.

- Energy Efficiency – Pumps can refill towers overnight when electricity demand is lower.

- Emergency Water Supply – If power fails, gravity can continue delivering water.

- Fire Protection – Fire hydrants depend on strong, immediate water pressure.

The Daily Fill-and-Use Cycle

Water towers typically operate on a daily cycle based on community demand.

- Night: Pumps refill the tower while water demand is low.

- Morning: Water levels drop as residents shower and prepare for the day.

- Daytime: Businesses and homes continue drawing water from the tower.

- Evening: The system begins refilling the tank for the next day.

How Much Water Can a Tower Store?

Water towers come in many sizes depending on the population they serve.

- Small towns: 50,000–300,000 gallons

- Suburban communities: 500,000–1 million gallons

- Larger urban systems: up to 2 million gallons or more

Even a single tower holding one million gallons can supply thousands of homes for several hours during peak demand or emergencies.

Modern Technology Inside Water Towers

Today’s water towers are equipped with advanced monitoring systems that help utilities maintain safe and reliable water supplies.

- Digital water level sensors

- Automated pump controls

- Water quality monitoring

- Protective interior coatings

- Regular inspections and maintenance

Landmarks in the American Skyline

Many cities turn their water towers into local landmarks by painting them with city names, mascots, or community slogans. Some towns even design towers shaped like giant objects such as fruit, coffee cups, or sports balls.

Despite their distinctive appearance, water towers remain one of the simplest and most reliable engineering solutions for delivering clean water to millions of Americans every day.

Next time you see a water tower rising above a town skyline, remember: it’s not just a landmark—it’s the gravity-powered system that keeps water flowing.

Related External Coverage

For more information about how water towers and municipal water systems work, explore the following resources:

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency – Drinking Water Regulations

- American Water Works Association – Water Storage and Water Towers

- HowStuffWorks – How Water Distribution Systems Work

- U.S. Geological Survey – Drinking Water and Groundwater Basics

- U.S. Department of Energy – How Water Towers Work

Dive into “The Knowledge,” where curiosity meets clarity. This playlist, in collaboration with STMDailyNews.com, is designed for viewers who value historical accuracy and insightful learning. Our short videos, ranging from 30 seconds to a minute and a half, make complex subjects easy to grasp in no time. Covering everything from historical events to contemporary processes and entertainment, “The Knowledge” bridges the past with the present. In a world where information is abundant yet often misused, our series aims to guide you through the noise, preserving vital knowledge and truths that shape our lives today. Perfect for curious minds eager to discover the ‘why’ and ‘how’ of everything around us. Subscribe and join in as we explore the facts that matter. https://stmdailynews.com/the-knowledge/

Discover more from Daily News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

unknown

The Unfavorable Semicircle Mystery: The YouTube Channel That Uploaded Tens of Thousands of Cryptic Videos

In 2015, the YouTube channel Unfavorable Semicircle gained attention for its enigmatic and abundant video uploads, totaling over 70,000 before its deletion in 2016. Theories about its purpose vary, from automated content generation to digital art experimentation, leaving its intent unresolved.

In the vast digital landscape of the internet, strange phenomena occasionally emerge that leave investigators, tech enthusiasts, and everyday viewers scratching their heads. One of the most puzzling cases appeared in 2015, when a mysterious YouTube channel called Unfavorable Semicircle began uploading an astonishing number of cryptic videos.

Within months, the channel had published tens of thousands of bizarre clips, many of which seemed random, incomprehensible, and visually chaotic. But as internet detectives began analyzing the content more closely, they discovered that these videos might not have been random at all.

The Sudden Appearance of an Internet Mystery

The Unfavorable Semicircle channel reportedly appeared in March 2015, with its first uploads arriving in early April.

Almost immediately, the channel began publishing videos at an incredible pace. Observers estimated that the account uploaded thousands of videos per week, sometimes multiple videos per minute. By the time the channel disappeared in early 2016, researchers believed it had uploaded well over 70,000 videos, possibly far more.

The scale alone made the project seem impossible for a human to manage manually.

Strange Visuals and Cryptic Titles

Most of the videos shared similar characteristics:

- Extremely short or very long runtime

- Abstract visuals such as flashing colors, static, or distorted imagery

- Little or no audio, or heavily distorted sounds

- Titles made of random characters, symbols, or numbers

To casual viewers, the videos looked like pure digital noise. However, online investigators suspected something more deliberate was happening.

Hidden Images Discovered

The mystery deepened when researchers began extracting individual frames from some videos.

When thousands of frames from certain clips were stitched together, the results sometimes formed coherent images. One of the most famous examples involved a video titled “LOCK.” While the footage appeared chaotic at first, combining the frames revealed a recognizable composite image.

This discovery suggested the videos were carefully constructed rather than random uploads.

Theories About the Channel’s Purpose

Because the creator never explained the project, several theories emerged across Reddit, YouTube, and internet forums.

Automated Experiment

Many believe the channel was created using automated software that generated and uploaded content at scale.

Alternate Reality Game (ARG)

Some viewers suspected the channel might be part of a hidden puzzle or digital scavenger hunt.

Encrypted Communication

Others compared the channel to Cold War “numbers stations,” suggesting the videos could contain coded messages.

Digital Art Project

Another theory suggests the channel was an experimental art project exploring algorithms, data, and visual noise.

Despite years of investigation, no single explanation has been confirmed.

Why the Channel Disappeared

In February 2016, YouTube removed the channel, reportedly due to spam or automated activity violations.

By that time, the channel had already become a minor internet legend. Fortunately, some researchers managed to archive a large portion of the videos before they disappeared.

Even today, archived clips continue to circulate online as investigators attempt to decode them.

Other Mysterious YouTube Channels

The Unfavorable Semicircle mystery is not the only strange case on YouTube.

One well-known example is Webdriver Torso, a channel that uploaded hundreds of thousands of videos showing red and blue rectangles with simple beeping sounds. Internet speculation ran wild before Google eventually confirmed it was an internal YouTube testing account.

Another example is AETBX, which posts distorted visuals and unusual audio that some viewers believe contain hidden patterns or encoded information.

These cases highlight how automation, experimentation, and creativity can sometimes blur the line between technology and mystery.

A Digital Mystery That Remains Unsolved

Nearly a decade later, the true purpose behind Unfavorable Semicircle remains unknown.

Was it a sophisticated experiment? A piece of algorithmic art? Or simply an automated test that accidentally captured the internet’s imagination?

Whatever the explanation, the channel stands as a reminder that even in a world filled with billions of videos and endless information, the internet can still produce mysteries that challenge our understanding of technology.

Why Internet Mysteries Still Fascinate Us

Stories like Unfavorable Semicircle capture attention because they combine technology, creativity, and the unknown. They invite people from around the world to collaborate, analyze patterns, and search for meaning hidden in the noise.

And sometimes, the most intriguing part of the mystery is that the answer may never fully be known.

Related Coverage & Further Reading

- Atlas Obscura – The Unsettling Mystery of the Creepiest Channel on YouTube

- Her Campus – Top 5 Most Obscure Internet Mysteries

- Medium – Unfavorable Semicircle: The YouTube Mystery No One Can Solve

- Gazette Review – Top 10 Strangest YouTube Channels Ever

- Decoding the Unknown – Unfavorable Semicircle YouTube Mystery Archive

- Wikipedia – Unfavorable Semicircle

Dive into “The Knowledge,” where curiosity meets clarity. This playlist, in collaboration with STMDailyNews.com, is designed for viewers who value historical accuracy and insightful learning. Our short videos, ranging from 30 seconds to a minute and a half, make complex subjects easy to grasp in no time. Covering everything from historical events to contemporary processes and entertainment, “The Knowledge” bridges the past with the present. In a world where information is abundant yet often misused, our series aims to guide you through the noise, preserving vital knowledge and truths that shape our lives today. Perfect for curious minds eager to discover the ‘why’ and ‘how’ of everything around us. Subscribe and join in as we explore the facts that matter. https://stmdailynews.com/the-knowledge/

Discover more from Daily News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Bridge

Celebrating International Women’s Day!

International Women’s Day is celebrated globally on March 8th to honor women’s achievements and promote gender equality, originating from a 1908 march in New York for better rights.

Last Updated on March 7, 2026 by Daily News Staff

International Women’s Day is a global celebration that honors the achievements of women and highlights the progress still to be made in the fight for gender equality. On this day, people around the world come together to recognize the amazing contributions of women everywhere and to rally for greater gender equity in all areas of life.

The origins of International Women’s Day can be traced back to 1908, when 15,000 women marched through the streets of New York City to demand better working conditions and the right to vote. Since then, the celebration has grown to be an international event, with more than 100 countries recognizing the day. The United Nations even declared March 8th as International Women’s Day in 1975, to honor the struggles of women around the world.

This year’s International Women’s Day theme is #ChooseToChallenge, meaning that everyone is encouraged to call out gender bias and inequality when they see it. We’re also encouraged to celebrate women’s achievements, support each other, and take action for equality.

It’s important to recognize the progress we’ve made in terms of gender equality, but we still have a long way to go. International Women’s Day serves as a reminder that we must continue to fight for gender equality in all areas of life. Let’s use this day to honor the contributions of women around the world, and to continue the fight for a more equitable world.

https://www.internationalwomensday.com/

https://stmdailynews.com/category/science/

Discover more from Daily News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.