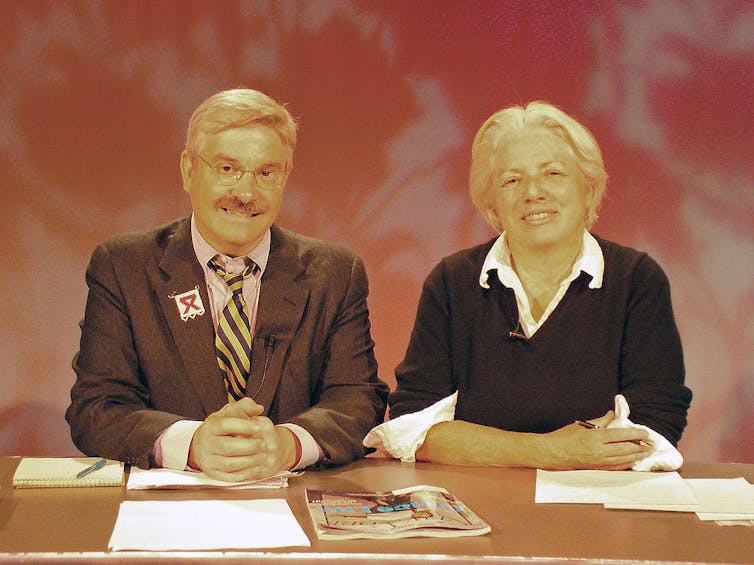

A record number of female candidates stood in the 2024 Japanese election.

Richard A. Brooks/AFP via Getty Images

Barriers to change

Today, around 60% of Japanese people – both men and women alike – approve of a change in the law to allow husbands and wives to have separate surnames. But to date, lawmakers have failed in their attempts to change a Civil Code that is seemingly at odds with the Constitution, which guarantees equality between men and women and between a husband and wife in marriage. The main barrier has been the conservative Liberal Democratic Party, or LDP, which has been in power for much of the post-World War II era. LDP lawmakers have repeatedly squashed proposals, stating that a legal change would threaten the traditional family structure. Since Japan’s Supreme Court in a 2015 decision sent the question of separate surnames back to the National Diet, the LDP has prevented legislation from reaching the parliamentary floor. But despite a largely male and conservative legislature, the government is facing increasing pressure from opposition members in parliament, who argue that separate surnames should be permitted in marriage. In Ishiba, the leader of the Liberal Democratic Party as well as the country’s leader, they finally have a powerful ally on the LDP side of the ledger.What’s in a name?

In Japan, a surname links a woman, or a man, to siblings, parents and grandparents, as well as to the places where their ancestors lived and worked. It’s a meaningful part of one’s identity. As a married woman I interviewed told me: “When they call me by my husband’s name at the bank, I feel they are referring to someone else. It doesn’t feel like me.” A woman technician checks a robot arm on the assembly line in Kitakyushu, Japan. Katsumi Kasahara/Gamma-Rapho via Getty ImagesBut beyond the symbolism and sense of identity, changing a surname has broader social consequences, especially in the workplace. The average age at marriage in Japan is 29.7 for women and 31 for men. By the time many women marry, they have been in the workforce for 10 or more years and have developed a professional identity using their maiden names. In Japan, work relationships are usually conducted using last names. As one interviewee explained to me: “We just don’t use first names at work in Japan.” Another interviewee said she wanted to have the same ease as her husband after marriage, to continue her profession with her own name. Contacting clients, co-workers, administrators and bosses about a name change draws attention to private matters that would not necessarily be discussed at work, she said. The concern among some women I spoke with is that once alerted to the change in marital status, bosses and colleagues will no longer take their commitment to the job as seriously as they did when they were single. Such feelings reveal the negative impact that marriage often has on a woman’s career – an effect some hope to avoid by not telling co-workers and clients of their changed status.

A woman technician checks a robot arm on the assembly line in Kitakyushu, Japan. Katsumi Kasahara/Gamma-Rapho via Getty ImagesBut beyond the symbolism and sense of identity, changing a surname has broader social consequences, especially in the workplace. The average age at marriage in Japan is 29.7 for women and 31 for men. By the time many women marry, they have been in the workforce for 10 or more years and have developed a professional identity using their maiden names. In Japan, work relationships are usually conducted using last names. As one interviewee explained to me: “We just don’t use first names at work in Japan.” Another interviewee said she wanted to have the same ease as her husband after marriage, to continue her profession with her own name. Contacting clients, co-workers, administrators and bosses about a name change draws attention to private matters that would not necessarily be discussed at work, she said. The concern among some women I spoke with is that once alerted to the change in marital status, bosses and colleagues will no longer take their commitment to the job as seriously as they did when they were single. Such feelings reveal the negative impact that marriage often has on a woman’s career – an effect some hope to avoid by not telling co-workers and clients of their changed status.Demographic time bomb

Conservative lawmakers decry a change of the surname rule in the Civil Code as an attack on traditional values and tie it to concerns over a looming demographic crisis. They argue that Japan must work to maintain the traditional family system and to encourage more marriages and babies. Certainly, Japan is facing a demographic crisis. With a fertility rate of around 1.2 babies per woman, Japan has one of the world’s oldest and fastest-shrinking populations. But Japanese scholars have argued that if women had more equality in the workplace, and at home, they would be more likely to choose to have children and continue working. Sociologist Aya Ezawa noted in 2019 that “a culture of long work hours, combined with a persistent gendered division of labour in the home, and high expectations toward motherhood mean that work and family remain very difficult to combine for women in contemporary Japan.” Former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, also a conservative LDP member, encouraged higher employment for women – married or unmarried – to help grow the Japanese economy in the early part of the 21st century. But his “Womenomics” plan bore little fruit. Without more policies addressing unequal treatment in the workplace, many educated and dedicated female workers will continue to be routed into dead-end jobs as their elder male bosses wait in vain for them to leave the workforce to have children. The vast majority of Japanese women give up their surnames upon marriage. Philip Fong/AFP via Getty Images

The vast majority of Japanese women give up their surnames upon marriage. Philip Fong/AFP via Getty Images