Child Health

Managing Birth Defects for a Lifetime

(Family Features) An estimated 1 in 33 babies is born with a birth defect, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). While some require minimal intervention after birth, many birth defects affect the individual, parents and families across a lifetime.

Birth defects are structural changes present at birth that can affect almost any part of the body. They may affect how the body looks, works or both. They can cause problems in overall health, how the body develops or how the body works, and may range from mild to serious health conditions.

Awareness of birth defects across the lifespan helps provide affected individuals, parents and families the information they need to seek proper care. Learn more about birth defects at each stage of life from the experts at March of Dimes:

Before and During Pregnancy

Not all birth defects are preventable but protecting a mother’s health before and during pregnancy can help increase the likelihood of a healthy baby. Having adequate folic acid for at least one month before getting pregnant and throughout the pregnancy can prevent major birth defects.

Other important steps include receiving proper prenatal care from a doctor, preventing infections, avoiding alcohol and drugs, controlling conditions like diabetes and avoiding getting too hot.

Infancy

Babies who are diagnosed with a birth defect during pregnancy or at birth may need special care. Similarly, monitoring for certain birth defects can help pinpoint a potential problem and ensure the baby begins receiving supportive care for better survival rates and quality of life. Examples include newborn screenings for critical congenital heart defects and monitoring bladder and kidney function in infants and children with spina bifida.

Childhood

For children born with heart defects and conditions like spina bifida, muscular dystrophy or Down syndrome, early intervention services and support can make a significant impact on a child’s success in school and life. They can help children with learning problems and disabilities; school attendance; participation in school, sports and clubs; mobility adaptations; and physical, occupational and speech therapy.

Adolescence

Many adolescents and young adults who have birth defects begin working toward a transition to a healthy, independent adult life in their later teen years. This may involve insurance changes and switching from pediatricians to adult doctors.

Other areas of focus might include medications, surgeries and other procedures; mental health; social development and relationships within and outside the family; physical activity; and independence.

Adulthood

Certain conditions, such as heart defects, can cause pregnancy complications or affect sexual function. Talking with a doctor about your specific condition can help you understand your risk.

In addition, every pregnancy carries a 3% risk of birth defects, even without lifestyle factors or health conditions that add risk, according to the CDC. Women who have had a pregnancy affected by a birth defect may be at greater risk during future pregnancies.

Talking with a health care provider can help assess those risks. A clinical geneticist or genetic counselor can assess your personal risk of birth defects caused by changes in genes, as well as your risk due to family history.

Find more information about birth defect prevention and management at marchofdimes.org/birthdefects.

Common Causes of Birth Defects

Research shows certain circumstances, or risk factors, may make a woman more likely to have a baby with a birth defect. Having a risk factor doesn’t mean a baby will be affected for sure, but it does increase the chances. Some of the more common causes of birth defects include:

Environment

The things that affect everyday life, including where you live, where you work, the kinds of foods you eat and how you like to spend your time can be harmful to your baby during pregnancy, especially if you’re exposed to potentially dangerous elements like cigarette smoke or harmful chemicals.

Health Conditions

Some health conditions, like pre-existing diabetes, can increase a baby’s risk of having a birth defect. Diabetes is a medical condition in which the body has too much sugar (called glucose) in the blood.

Medications

Taking certain medicines while pregnant, like isotretinoin (a medicine used to treat acne), can increase the risk of birth defects.

Smoking, Drinking or Using Drugs

Lifestyle choices that affect your own health and well-being are likely to affect an unborn baby. Smoking, drinking or using drugs can cause numerous problems for a baby, including birth defects.

Infections

Some infections during pregnancy can increase the risk of birth defects and other problems. For example, if an expectant mother has a Zika infection during pregnancy, her baby may be at increased risk of having microcephaly.

Age

Women who are 34 years old or older may be at increased risk of having a baby with a birth defect.

Photos courtesy of Getty Images

SOURCE:

March of Dimes

Discover more from Daily News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Child Health

A Parent’s Guide to Navigating Picky Eating with Confidence

For families with young children, mealtimes can often feel like negotiations or even battles. If that sounds familiar, you’re not alone. Picky eating is one of the most universal challenges families face. With the right strategies, parents can reduce stress, build healthier habits and help children become more confident, curious eaters.

(Feature Impact)For families with young children, mealtimes can often feel like negotiations or even battles. If that sounds familiar, you’re not alone. Picky eating is one of the most universal challenges families face.

With the right strategies, parents can reduce stress, build healthier habits and help children become more confident, curious eaters. Dr. Lauren Loquasto, senior vice president and chief academic officer at The Goddard School, and registered dietitian Ali Bandier, founder of Senta Health and member of the Expert Council at Little Spoon, share these insights and guidance to help parents navigate picky eating.

Why Young Children are Picky Eaters

Picky eating isn’t just common; it’s an expected part of early childhood development. In fact, it would be more surprising if children didn’t experience a picky eating phase.

Picky eating is a natural expression of independence. As children enter toddlerhood, they discover they can assert control, and food becomes a typical place to do it. They can’t decide whether to go to school or take a bath, but they can decide whether to take a bite of broccoli.

Avoid the Power Struggle

The key for parents: stay calm, consistent and neutral. Pressuring children only makes picky eating worse.

Telling your child they must try one bite, celebrating excessively when they do eat a vegetable or resorting to negotiation (“three more bites then dessert”) can actually reduce their desire to eat. It also creates a dynamic that only reinforces the power struggle.

Instead, recognize the division of responsibility when it comes to eating. Parents decide what food is served, when it’s served and where meals happen. Children decide whether to eat and how much to eat. As a parent, you can’t force your child to eat; recognizing this is critical to reducing the mealtime tug‑of‑war and creating a calmer, more predictable environment for the entire family.

Exposure, Not Pressure

Young children often need repeated, low‑pressure exposure to a new food before trying it. Offering broccoli once likely isn’t enough. It’s important to offer it repeatedly, without commentary, bribing or coaxing.

Trying new foods is more than just ingesting them. Touching and smelling are steps toward tasting and acceptance. Involving children in food preparation – washing vegetables, stirring batter, mixing ingredients – lets them gain familiarity without the pressure of having to eat. Inclusion in this process increases curiosity and that curiosity is often followed by a willingness, or even desire, to try the food.

It’s also important for parents to model desired eating habits. If you want your child to try salmon but you’re eating pizza, they’re unlikely to want to eat the salmon. Daily family mealtimes – often dinner in busy households – where you’re modeling manners and eating the food you want your child to eat is key.

The Importance of Routines

For young children, routines provide structure, predictability and comfort. A consistent meal and snack schedule helps children learn what to expect and can reduce not only their anxiety around mealtimes, but parental anxiety, too.

Notably, there is no right or wrong schedule; every family needs to figure out what works best for their circumstances. What matters is setting a schedule and maintaining consistency. For example, if you provide a snack between breakfast and lunch, do it every day, not just a few days a week. This helps children know what to expect and feel comfortable.

Schedules also help parents resist “secondhand cooking.” When a child refuses the meal offered, parents often scramble to make alternatives, but this teaches the child if they hold out long enough, a preferred food will arrive. Instead, calmly remind your child when the next snack or meal will be: “OK, you don’t want to have the yogurt and fruit. That’s fine, but I’m not going to make something else. Snack time is in two hours.” This builds trust and reduces anxiety for everyone.

With patience, low-pressure exposure and consistent routines, most picky eaters gradually broaden their palates and mealtimes become more enjoyable for the whole family. For more parenting guidance, including the Parenting with Goddard blog and webinar series, visit the Parent Resource Center at GoddardSchool.com.

Photos courtesy of Shutterstock

![]()

SOURCE:

At our core, we at STM Daily News, strive to keep you informed and inspired with the freshest content on all things food and beverage. From mouthwatering recipes to intriguing articles, we’re here to satisfy your appetite for culinary knowledge.

Visit our Food & Drink section to get the latest on Foodie News and recipes, offering a delightful blend of culinary inspiration and gastronomic trends to elevate your dining experience. https://stmdailynews.com/food-and-drink/

Discover more from Daily News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Child Health

Why Simple Daily Habits Matter More Than Big Health Resolutions

(Feature Impact) Most people don’t set out to ignore their health. It usually slips down the list somewhere between the morning alarm and the last email of the day. Breakfast gets rushed or skipped. Exercise is postponed until tomorrow. Sleep is cut short to catch up on everything else. By the end of the week, healthy intentions are still there, but the follow-through feels harder than expected.

For many, the challenge is not motivation but finding habits that fit into real life. Small, repeatable choices around sleep, exercise, nutrition, mental well-being and social connection can support how the body and mind function over time.

Sleep Well

Sleep is essential for physical recovery, mental focus and emotional balance, but it’s often the first habit to slip when schedules get busy.

Establishing a regular bedtime routine helps signal when it’s time to rest. Limiting screen exposure in the evening, keeping sleep and wake times consistent and creating a dark, quiet sleep environment can support more restorative sleep. Over time, better sleep contributes to improved mood, focus and overall heart health.

Exercise in Manageable Ways

Exercise often falls into the same trap as sleep. When schedules get full, it becomes something to get back to rather than something that fits into the day as it unfolds. A missed workout can quickly turn into a missed week, even for people who value staying active.

Regular movement supports heart health, muscle strength and overall energy, but it doesn’t need to be all-or-nothing. Short periods of activity spread throughout the day can still make a difference, especially when long stretches of sitting are the default.

Walking between meetings, stretching in the morning or adding light strength exercises at home are simple ways to stay active without blocking out extra time.

Eat Nutritiously

Food decisions often happen on autopilot as meals are squeezed into busy schedules and long days, making nutrition one of the most influential daily habits.

Meals do more than provide fuel. When built around nutrient-rich foods, they support muscle health, brain health and heart health. An overall healthy eating pattern includes a variety of whole foods like fruits, vegetables, whole grains and lean proteins, helping the body keep up with everyday demands.

Protein plays an important role in maintaining muscle and supporting daily movement, especially as people age. High-quality protein from foods, along with a balanced diet and regular exercise, can help support all the muscles in the body. Choosing protein sources that are easy to prepare and repeat supports consistency when schedules are full.

As part of a balanced approach to healthy habits, nutrition guidance from the American Heart Association’s Healthy for Good initiative, nationally sponsored by the Egg Nutrition Center, highlights how everyday food choices can support the body and brain over time. Eggs are an example of a high-quality protein and they fit easily into meals throughout the day.

Eggs also deliver choline, a nutrient many Americans don’t get enough of. Choline is a critical nutrient, among others, for supporting brain development, memory and mood. Along with protein, choline helps support brain health, making it an important consideration across life stages.

According to the American Heart Association, healthy people can include one egg daily, up to seven eggs per week, as part of a heart-healthy diet. For healthy older adults with normal cholesterol, two eggs per day can be included as part of a heart-healthy dietary pattern.

Mind Your Mental Well-Being

The way people eat, sleep and move does not just affect the body. It also shapes how the brain responds to stress and daily demands. When routines feel rushed or inconsistent, mental well-being is often one of the first areas to feel the strain.

Ongoing stress can interfere with focus, sleep and eating habits, making it harder to maintain healthy routines. Simple practices like deep breathing, mindfulness or stepping away from screens for a few minutes can help reduce tension and restore attention.

Making time for rest and reflection, and setting realistic expectations, can also support emotional balance. What supports the brain often supports the heart as well, reinforcing the value of caring for mental and physical health together.

Socialize and Stay Connected

Mental well-being is shaped by both daily routines and relationships. When life feels busy or stressful, social connection is often the first thing to get pushed aside, even though it plays an important role in emotional health.

Staying connected doesn’t require packed calendars or constant interaction. Shared meals, short conversations or a quick check-in with a friend or family member can help maintain a sense of connection.

Build Habits That Fit Real Life

Healthy routines are more likely to last when they fit into the rhythm of everyday life rather than compete with it. Big changes can feel motivating at first, but it is often the small, repeatable choices that quietly shape how people feel over time.

Choosing foods that are easy to prepare, finding enjoyable ways to exercise and protecting time for sleep can make healthy habits feel more realistic. When routines are built around what is already happening during a typical day, they are easier to return to even when schedules get busy.

For more information and educational resources on nutrition and healthy living, visit Heart.org.

Photos courtesy of Shutterstock

![]()

SOURCE:

Our Lifestyle section on STM Daily News is a hub of inspiration and practical information, offering a range of articles that touch on various aspects of daily life. From tips on family finances to guides for maintaining health and wellness, we strive to empower our readers with knowledge and resources to enhance their lifestyles. Whether you’re seeking outdoor activity ideas, fashion trends, or travel recommendations, our lifestyle section has got you covered. Visit us today at https://stmdailynews.com/category/lifestyle/ and embark on a journey of discovery and self-improvement.

Discover more from Daily News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

News

Children can be systematic problem-solvers at younger ages than psychologists had thought – new research

Child psychologists: Celeste Kidd’s research challenges long-standing ideas from Jean Piaget about children’s problem-solving abilities. Her findings show that children as young as four can independently utilize algorithmic strategies to solve complex tasks, contradicting the belief that systematic logical thinking develops only after age seven. This insight highlights the importance of nurturing algorithmic thinking in early education.

Last Updated on March 8, 2026 by Daily News Staff

Celeste Kidd, University of California, Berkeley

I’m in a coffee shop when a young child dumps out his mother’s bag in search of fruit snacks. The contents spill onto the table, bench and floor. It’s a chaotic – but functional – solution to the problem.

Children have a penchant for unconventional thinking that, at first glance, can look disordered. This kind of apparently chaotic behavior served as the inspiration for developmental psychologist Jean Piaget’s best-known theory: that children construct their knowledge through experience and must pass through four sequential stages, the first two of which lack the ability to use structured logic.

Piaget remains the GOAT of developmental psychology. He fundamentally and forever changed the world’s view of children by showing that kids do not enter the world with the same conceptual building blocks as adults, but must construct them through experience. No one before or since has amassed such a catalog of quirky child behaviors that researchers even today can replicate within individual children.

While Piaget was certainly correct in observing that children engage in a host of unusual behaviors, my lab recently uncovered evidence that upends some long-standing assumptions about the limits of children’s logical capabilities that originated with his work. Our new paper in the journal Nature Human Behaviour describes how young children are capable of finding systematic solutions to complex problems without any instruction. https://www.youtube.com/embed/Qb4TPj1pxzQ?wmode=transparent&start=0 Jean Piaget describes how children of different ages tackle a sorting task, with varying success.

Putting things in order

Throughout the 1960s, Piaget observed that young children rely on clunky trial-and-error methods rather than systematic strategies when attempting to order objects according to some continuous quantitative dimension, like length. For instance, a 4-year-old child asked to organize sticks from shortest to longest will move them around randomly and usually not achieve the desired final order.

Psychologists have interpreted young children’s inefficient behavior in this kind of ordering task – what we call a seriation task – as an indicator that kids can’t use systematic strategies in problem-solving until at least age 7.

Somewhat counterintuitively, my colleagues and I found that increasing the difficulty and cognitive demands of the seriation task actually prompted young children to discover and use algorithmic solutions to solve it.

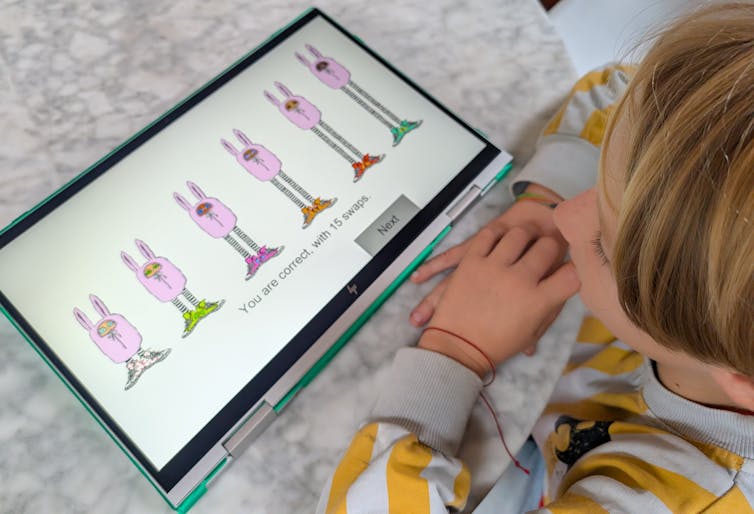

Piaget’s classic study asked children to put some visible items like wooden sticks in order by height. Huiwen Alex Yang, a psychology Ph.D. candidate who works on computational models of learning in my lab, cranked up the difficulty for our version of the task. With advice from our collaborator Bill Thompson, Yang designed a computer game that required children to use feedback clues to infer the height order of items hidden behind a wall, .

The game asked children to order bunnylike creatures from shortest to tallest by clicking on their sneakers to swap their places. The creatures only changed places if they were in the wrong order; otherwise they stayed put. Because they could only see the bunnies’ shoes and not their heights, children had to rely on logical inference rather than direct observation to solve the task. Yang tested 123 children between the ages of 4 and 10. https://www.youtube.com/embed/GlsbcE6nOxk?wmode=transparent&start=0 Researcher Huiwen Alex Yang tests 8-year-old Miro on the bunny sorting task. The bunnies are hidden behind a wall with only their sneakers visible. Miro’s selections exemplify use of selection sort, a classic efficient sorting algorithm from computer science. Kidd Lab at UC Berkeley.

Figuring out a strategy

We found that children independently discovered and applied at least two well-known sorting algorithms. These strategies – called selection sort and shaker sort – are typically studied in computer science.

More than half the children we tested demonstrated evidence of structured algorithmic thinking, and at ages as young as 4 years old. While older kids were more likely to use algorithmic strategies, our finding contrasts with Piaget’s belief that children were incapable of this kind of systematic strategizing before 7 years of age. He thought kids needed to reach what he called the concrete operational stage of development first.

Our results suggest that children are actually capable of spontaneous logical strategy discovery much earlier when circumstances require it. In our task, a trial-and-error strategy could not work because the objects to be ordered were not directly observable; children could not rely on perceptual feedback.

Explaining our results requires a more nuanced interpretation of Piaget’s original data. While children may still favor apparently less logical solutions to problems during the first two Piagetian stages, it’s not because they are incapable of doing otherwise if the situation requires it.

A systematic approach to life

Algorithmic thinking is crucial not only in high-level math classes, but also in everyday life. Imagine that you need to bake two dozen cookies, but your go-to recipe yields only one. You could go through all the steps of making the recipe twice, washing the bowl in between, but you’d never do that because you know that would be inefficient. Instead, you’d double the ingredients and perform each step only once. Algorithmic thinking allows you to identify a systematic way of approaching the need for twice as many cookies that improves the efficiency of your baking.

Algorithmic thinking is an important capacity that’s useful to children as they learn to move and operate in the world – and we now know they have access to these abilities far earlier than psychologists had believed.

That children can engage with algorithmic thinking before formal instruction has important implications for STEM – science, technology, engineering and math –education. Caregivers and educators now need to reconsider when and how they give children the opportunity to tackle more abstract problems and concepts. Knowing that children’s minds are ready for structured problems as early as preschool means we can nurture these abilities earlier in support of stronger math and computational skills.

And have some patience next time you encounter children interacting with the world in ways that are perhaps not super convenient. As you pick up your belongings from a café floor, remember that it’s all part of how children construct their knowledge. Those seemingly chaotic kids are on their way to more obviously logical behavior soon.

Celeste Kidd, Professor of Psychology, University of California, Berkeley

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Dive into “The Knowledge,” where curiosity meets clarity. This playlist, in collaboration with STMDailyNews.com, is designed for viewers who value historical accuracy and insightful learning. Our short videos, ranging from 30 seconds to a minute and a half, make complex subjects easy to grasp in no time. Covering everything from historical events to contemporary processes and entertainment, “The Knowledge” bridges the past with the present. In a world where information is abundant yet often misused, our series aims to guide you through the noise, preserving vital knowledge and truths that shape our lives today. Perfect for curious minds eager to discover the ‘why’ and ‘how’ of everything around us. Subscribe and join in as we explore the facts that matter. https://stmdailynews.com/the-knowledge/

Discover more from Daily News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.