The Bridge

Accept our king, our god − or else: The senseless ‘requirement’ Spanish colonizers used to justify their bloodshed in the Americas

The Requerimiento legally coerced Indigenous peoples into submission under Spanish rule, often leading to violence, despite its absurdity, revealing colonialism’s brutal legacy.

Diego Javier Luis, Johns Hopkins University

Across the United States, the second Monday of October is increasingly becoming known as Indigenous Peoples Day. In the push to rename Columbus Day, Christopher Columbus himself has become a metaphor for the evils of early colonial empires, and rightly so.

The Italian explorer who set out across the Atlantic in search of Asia was a notorious advocate for enslaving the Indigenous Taínos of the Caribbean. In the words of historian Andrés Reséndez, he “intended to turn the Caribbean into another Guinea,” the region of West Africa that had become a European slave-trading hub.

By 1506, however, Columbus was dead. Most of the genocidal acts of violence that defined the colonial period were carried out by many, many others. In the long shadow of Columbus, we sometimes lose sight of the ideas, laws and ordinary people who enabled colonial violence on a large scale.

As a historian of colonial Latin America, I often begin such discussions by pointing to a peculiar document drafted several years after Columbus’ death that would have greater repercussions for Indigenous peoples than Columbus himself: the Requerimiento, or “Requirement.”

Catch-22

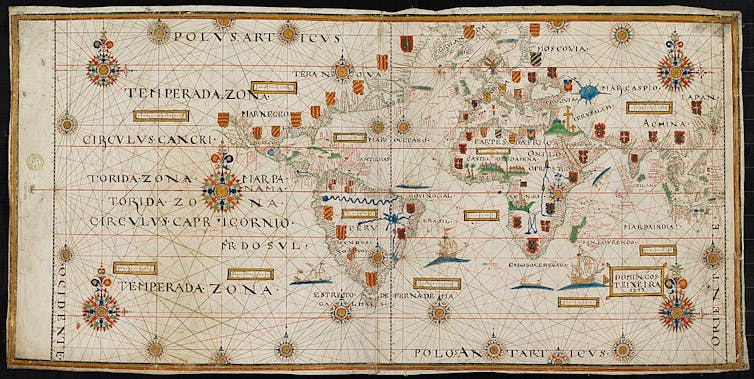

In 1494, the Treaty of Tordesillas infamously divided much of the world beyond Europe into two halves: one for the Spanish crown, the other for the Portuguese. Spaniards lay claim to almost the entirety of the Americas, though they knew almost nothing about this vast domain or the people who lived there.

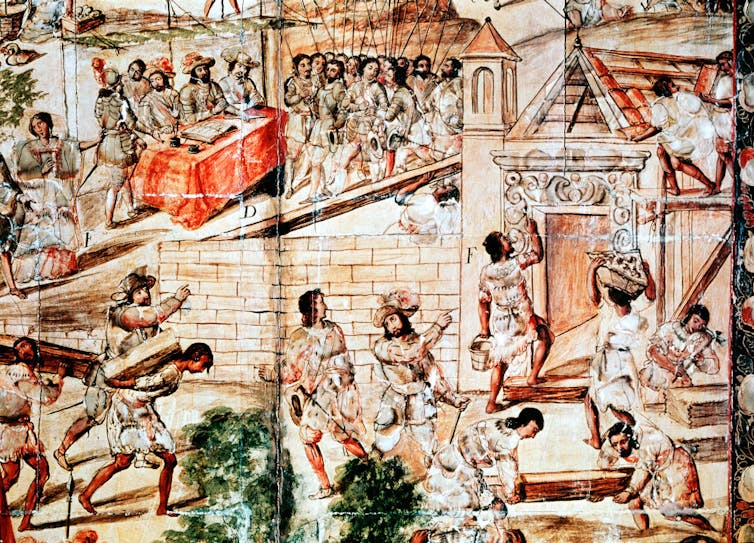

In order to inform Indigenous people that they had suddenly become vassals of Spain, King Ferdinand and his councilors instructed colonizers to read the Requerimiento aloud upon first contact with all Indigenous groups.

The document presented them with a choice that was no choice at all. They could either become Christians and submit to the authority of the Catholic Church and the king, or else:

“With the help of God, we shall powerfully enter into your country, and shall make war against you in all ways and manners that we can … we shall take you and your wives and your children and shall make slaves of them … the deaths and losses which shall accrue from this are your fault.”

It was a catch-22. According to the document, Indigenous people could either voluntarily surrender their sovereignty and become vassals or bring war upon themselves – and perhaps lose their sovereignty anyway, after much bloodshed. No matter what they chose, the Requerimiento supplied the legal pretext for forcibly incorporating sovereign Indigenous peoples into the Spanish domain.

At its core, the Requerimiento was a legal ritual, a performance of possession – and it was unique to early Spanish imperialism.

‘As absurd as it is stupid’

But for all of its seeming authority, the reading of the Requerimiento was an absurd exercise. It first occurred at what is now Santa Marta, Colombia, during the expedition led by Pedrarias Dávila in 1513. An eyewitness, the chronicler Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo, stated the obvious: “we have no one here who can help [the Indigenous people] understand it.”

Even with a translator, though, the document – with its lofty references to the Biblical creation of the world and papal authority – would hardly be intelligible to people unfamiliar with the Spaniards’ religion. Explaining the convoluted document would require nothing less than a long recitation of Catholic history.

Oviedo suggested that to deliver such a lecture, you’d have to first capture and cage an Indigenous person. Even then, it would be impossible to verify whether the document had been fully understood.

However, for the Requerimiento’s greatest critic, Bartolomé de las Casas, translation was merely one of many problems. A missionary from Spain, Las Casas criticized the spurious requirement itself: that a people should be expected to immediately convert to a religion they have only just learned exists, and

“swear allegiance to a king they have never heard of nor clapped eyes on, and whose subjects and ambassadors prove to be cruel, pitiless and bloodthirsty tyrants. … Such a notion is as absurd as it is stupid and should be treated with the disrespect, scorn and contempt it so amply deserves.”

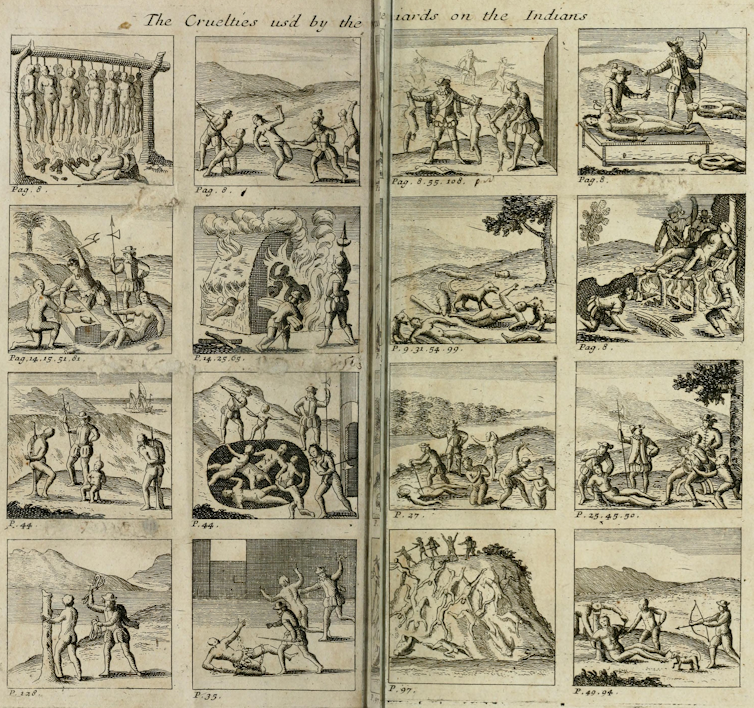

Las Casas, who documented abuses against Indigenous people in multiple books and speeches, was one of the most outspoken denouncers of Spanish cruelty in the Americas. While he believed Spaniards had a right and even an obligation to convert Indigenous people to Catholicism, he did not believe that conversion should be done under the threat of violence.

Wars and forced settlement

Indigenous people responded to the Requerimiento in numerous ways. When the Chontal Maya of Potonchan – a Maya capital now part of Mexico – heard the conquistador Hernando Cortés read the document three consecutive times, they answered with arrows. After Cortés captured the town, they agreed to become Christian vassals of Spain on the condition that the Spaniards “leave their land.” When Cortés’ men remained after three days, the Chontal Maya attacked again.

Farther north, Spanish expeditioners Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca and Melchior Díaz used the Requerimiento to forcibly relocate various Indigenous groups.

A bloodthirsty governor of the province, Nuño Beltrán de Guzmán – so violent that the Spanish themselves imprisoned him for abuses of power – had driven Indigenous residents out of the Valley of Culiacan in a series of brutal wars. But in 1536, Cabeza de Vaca and Díaz forced several groups, including the Tahue, to repopulate the valley after convincing them to accept the terms of the Requerimiento.

Resettlement would enable the collection of tribute and conversion to Catholicism. It was simply easier to assign missionaries and tribute collectors to established Hispanic townships than to mobile communities spread out across vast territories.

Cabeza de Vaca encouraged Indigenous leaders to accept the proposition by claiming that their god, Aguar, was the same as the Christians’, and so they should “serve him as we commanded.” In such cases, conversion to Catholicism was just as farcical as the Requerimiento itself.

Violence and colonial legacy

Even when Indigenous people accepted the Requerimiento, however, Las Casas wrote that “they are (still) harshly treated as common slaves, put to hard labor and subjected to all manner of abuse and to agonizing torments that ensure a slower and more painful death than would summary execution.” In most cases, the Requerimiento was simply a precursor to violence.

Dávila, the conquistador of present-day northern Colombia, once read it out of earshot of a village just before launching a surprise attack. Others read the Requerimiento “to trees and empty huts” before drawing their swords. The path to vassalage was paved in blood.

These are the truest indications of what the Requerimiento became on the ground. Soldiers and officials were content to violently deploy or discard royal prerogatives as they pleased in their pursuit of the spoils of war.

And yet, despite the viciousness, many Indigenous peoples survived by stringing their bows like the Chontal Maya, or negotiating a new relationship with Spain like the Tahue of Culiacan. Tactics varied greatly and changed over time.

Many Indigenous nations that exercised them survive today, long outliving the Spanish Empire – and the people who carried the Requerimiento on their crusade across the Americas.

Diego Javier Luis, Assistant Professor of History, Johns Hopkins University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The Bridge is a section of the STM Daily News Blog meant for diversity, offering real news stories about bona fide community efforts to perpetuate a greater good. The purpose of The Bridge is to connect the divides that separate us, fostering understanding and empathy among different groups. By highlighting positive initiatives and inspirational actions, The Bridge aims to create a sense of unity and shared purpose. This section brings to light stories of individuals and organizations working tirelessly to promote inclusivity, equality, and mutual respect. Through these narratives, readers are encouraged to appreciate the richness of diverse perspectives and to participate actively in building stronger, more cohesive communities.

https://stmdailynews.com/the-bridge

Discover more from Daily News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Bridge

Hard Rock International and Coca-Cola Launch ‘Women Empower’ Series for International Women’s Month

Hard Rock International is teaming up with long-time partner Coca-Cola to spotlight women shaping the music business with a new content initiative and a month-long slate of events.

Announced Feb. 26, 2026, the collaboration introduces “Women Empower,” a micro-documentary series rolling out throughout March as part of Hard Rock’s annual International Women’s Month celebrations. Alongside the video series, Hard Rock says it’s aiming to host 1,000 live music and special events globally across its Cafes, Hotels, Casinos and Live venues.

A micro-documentary series focused on women across the industry

Rather than focusing only on performers, “Women Empower” highlights women working in a range of roles across music and media. Hard Rock notes that less than 5% of music and media creators are women, and the series is designed to put more faces—and job titles—into the public conversation.

The six featured women include:

- Janelle Abraham — Director/Film Producer

- Kat Luna — Singer/Songwriter

- Minami Minami — Composer/Dancer/Singer

- Claire Murphy — Guitar Tech

- Mayna Nevarez — CEO & Founder, Nevarez Communications

- Wendy Ong — Co-President/CMO, TaP Music

Elena Alvarez, Senior Vice President of Marketing and Brand Partnerships at Seminole Gaming and Hard Rock International, said the brand is using International Women’s Month to “lift the curtain” on the series while tying the celebration back to Hard Rock’s music-first identity and philanthropic work.

$100,000 donation to Women in Music

Hard Rock Heals Foundation®, Hard Rock’s charitable arm, is donating $100,000 to Women in Music, supporting the nonprofit’s education and empowerment efforts.

Nicole Barsalona, President of Women in Music, said the campaign highlights diversity on stage and “the wide range of roles across the music business—and the women behind the scenes whose work drives our industry forward.”

Limited-time Coca-Cola menu items at participating Hard Rock Cafes

Throughout March, participating Hard Rock Cafes will offer a limited-time Coca-Cola-inspired menu tied to the regions represented in the series.

Specialty drinks include:

- Passionfruit Splash — passionfruit beverage with Minute Maid Lemonade, Sprite and cranberry juice

- Mango Guava Chiller — mango and guava-flavored drink with Sprite, pineapple and lime juice

- Spiced Yuzu Soda — spiced brown sugar, yuzu and Coca-Cola blend

Food items include:

- Fattoush Chicken Caesar Salad — romaine with grilled chicken, mint, vegetables, fried naan and red wine Caesar dressing

- Mahi Sandwich — mahi filet with remoulade, lettuce, tomato and shoestring onions, served with seasoned fries

- Dulce de Leche Brownie — brownie with chocolate sauce, vanilla ice cream, dulce de leche and whipped cream

Hard Rock Hotels: curated listening experiences honoring female artists

Hard Rock Hotels will also highlight women in music through live performances, curated playlists and themed listening experiences using the brand’s Sound of Your Stay® program. Hard Rock says guests can expect music-themed amenities such as limited-edition vinyl, memorabilia highlights and playlists centered on female artists—both iconic names and emerging talent.

Events worldwide + Rock Shop merch

Hard Rock says it will host women-led performances, networking events, brunches and other community-driven experiences across its global footprint throughout March.

Hard Rock’s official International Women’s Month T-shirts are available at Rock Shop® retail locations and online.

For the full list of International Women’s Month activations, visit https://www.hardrock.com/women.

The Bridge is a section of the STM Daily News Blog meant for diversity, offering real news stories about bona fide community efforts to perpetuate a greater good. The purpose of The Bridge is to connect the divides that separate us, fostering understanding and empathy among different groups. By highlighting positive initiatives and inspirational actions, The Bridge aims to create a sense of unity and shared purpose. This section brings to light stories of individuals and organizations working tirelessly to promote inclusivity, equality, and mutual respect. Through these narratives, readers are encouraged to appreciate the richness of diverse perspectives and to participate actively in building stronger, more cohesive communities.

https://stmdailynews.com/the-bridge

Discover more from Daily News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Community

Chick-fil-A Awards $6 Million in True Inspiration Awards Grants to 56 Nonprofits

Chick-fil-A is awarding $6 million in 2026 True Inspiration Awards grants to 56 nonprofits, including a $350,000 honoree grant to San Antonio’s Faith Kitchen.

Last Updated on February 26, 2026 by Daily News Staff

Chick-fil-A, Inc. is awarding $6 million in grants to 56 nonprofit organizations as part of its 2026 True Inspiration Awards® program, spotlighting groups the company says are making measurable, community-level impact.

The Feb. 10 announcement also marks a global milestone for the brand: Chick-fil-A is expanding the program’s footprint to include its first-ever Singapore-based grant recipient.

The big picture: a decade of community grants

Chick-fil-A launched the True Inspiration Awards in 2015 to honor the legacy of its founder, S. Truett Cathy. Since then, the company says it has awarded more than 400 grants totaling nearly $40 million to nonprofits across the U.S., Canada, Puerto Rico, the U.K. and now Singapore.

“Serving is at the heart of what we do, and the True Inspiration Awards reflect our belief that strong communities are built through consistent, caring action,” said Andrew T. Cathy, CEO of Chick-fil-A, Inc., in the release.

Faith Kitchen named 2026 S. Truett Cathy Honoree

This year’s S. Truett Cathy Honoree — the program’s top recognition and largest grant — went to Faith Kitchen, a San Antonio-based nonprofit focused on serving people experiencing homelessness.

Faith Kitchen received a $350,000 grant, which Chick-fil-A says will help:

- Support continued meal service

- Expand job training programs

- Increase operational capacity as demand rises

According to the release, Faith Kitchen serves more than 5,000 individuals each year and has operated with a mission of feeding those experiencing homelessness for 45 years, providing hot, nutritious meals three times per day.

Shared Table partnership: surplus food turned into meals

Chick-fil-A also highlighted its ongoing relationship with Faith Kitchen through the Chick-fil-A Shared Table®program, which donates surplus food from restaurants.

Since 2017, Chick-fil-A restaurants in San Antonio have partnered with Faith Kitchen to help create more than 200,000 meals, according to the company. The release also notes restaurants donate 500 boxed meals monthly to support Faith Kitchen clients.

Local Owner-Operator Greg Patterson said he nominated Faith Kitchen for the grant, citing the organization’s focus on dignity and dependable support.

Global expansion: first Singapore recipient

A notable headline for 2026 is the program’s first Singapore recipient: Fei Yue Community Services, which received $170,000 SGD.

Chick-fil-A says the organization supports socially withdrawn youth by connecting them with mental health resources and supportive relationships.

More nonprofits recognized across the U.S.

While Chick-fil-A’s full list of 2026 recipients is available through the company’s program page, the release highlights several additional grant recipients, including:

- Living and Learning Enrichment Center (Detroit, Michigan): $125,000 to support teens and young adults with disabilities transitioning to adulthood

- For Oak Cliff (North Texas): $200,000 to strengthen culturally responsive programs and expand access to education, workforce development, and community resources

- San Diego Rescue Mission (San Diego, California): $125,000 to provide trauma-informed support for individuals and families facing homelessness

- Capital City Youth Services (Tallahassee, Florida): selected to help expand emergency shelter and mental health support for at-risk youth

Chick-fil-A One members helped vote — nearly 700,000 ballots

Chick-fil-A says Chick-fil-A One® Members voted for Operator-nominated nonprofits in the Chick-fil-A App, and that voting plays a role in the final scoring. This year, the company reported a record nearly 700,000 votes cast.

2027 application window is open

Nonprofits interested in the next cycle can take note: Chick-fil-A says the 2027 True Inspiration Awards application period opens today and closes May 1.

For more information and the interactive release, visit: https://www.multivu.com/chick-fil-a/9376351-en-chick-fil-a-true-inspiration-awards-grants

Our Lifestyle section on STM Daily News is a hub of inspiration and practical information, offering a range of articles that touch on various aspects of daily life. From tips on family finances to guides for maintaining health and wellness, we strive to empower our readers with knowledge and resources to enhance their lifestyles. Whether you’re seeking outdoor activity ideas, fashion trends, or travel recommendations, our lifestyle section has got you covered. Visit us today at https://stmdailynews.com/category/lifestyle/ and embark on a journey of discovery and self-improvement.

Discover more from Daily News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Urbanism

The Building That Proved Los Angeles Could Go Vertical

Los Angeles once banned skyscrapers, yet City Hall broke the height limit and proved high-rise buildings could be engineered safely in an earthquake zone.

Last Updated on February 19, 2026 by Daily News Staff

How City Hall Quietly Undermined LA’s Own Height Limits

The Knowledge Series | STM Daily News

For more than half a century, Los Angeles enforced one of the strictest building height limits in the United States. Beginning in 1905, most buildings were capped at 150 feet, shaping a city that grew outward rather than upward.

The goal was clear: avoid the congestion, shadows, and fire dangers associated with dense Eastern cities. Los Angeles sold itself as open, sunlit, and horizontal — a place where growth spread across land, not into the sky.

And yet, in 1928, Los Angeles City Hall rose to 454 feet, towering over the city like a contradiction in concrete.

It wasn’t built to spark a commercial skyscraper boom.

But it ended up proving that Los Angeles could safely build one.

A Rule Designed to Prevent a Manhattan-Style City

The original height restriction was rooted in early 20th-century fears:

- Limited firefighting capabilities

- Concerns over blocked sunlight and airflow

- Anxiety about congestion and overcrowding

- A strong desire not to resemble New York or Chicago

Los Angeles wanted prosperity — just not vertical density.

The height cap reinforced a development model where:

- Office districts stayed low-rise

- Growth moved outward

- Automobiles became essential

- Downtown never consolidated into a dense core

This philosophy held firm even as other American cities raced upward.

Why City Hall Was Never Meant to Change the Rules

City Hall was intentionally exempt from the height limit because the law applied primarily to private commercial buildings, not civic monuments.

But city leaders were explicit about one thing:

City Hall was not a precedent.

It was designed to:

- Serve as a symbolic seat of government

- Stand alone as a civic landmark

- Represent stability, authority, and modern governance

- Avoid competing with private office buildings

In effect, Los Angeles wanted a skyline icon — without a skyline.

Innovation Hidden in Plain Sight

What made City Hall truly significant wasn’t just its height — it was how it was built.

At a time when seismic science was still developing, City Hall incorporated advanced structural ideas for its era:

- A steel-frame skeleton designed for flexibility

- Reinforced concrete shear walls for lateral strength

- A tapered tower to reduce wind and seismic stress

- Thick structural cores that distributed force instead of resisting it rigidly

These choices weren’t about aesthetics — they were about survival.

The Earthquake That Changed the Conversation

In 1933, the Long Beach earthquake struck Southern California, causing widespread damage and reshaping building codes statewide.

Los Angeles City Hall survived with minimal structural damage.

This moment quietly reshaped the debate:

- A tall building had endured a major earthquake

- Structural engineering had proven effective

- Height alone was no longer the enemy — poor design was

City Hall didn’t just survive — it validated a new approach to vertical construction in seismic regions.

Proof Without Permission

Despite this success, Los Angeles did not rush to repeal its height limits.

Cultural resistance to density remained strong, and developers continued to build outward rather than upward. But the technical argument had already been settled.

City Hall stood as living proof that:

- High-rise buildings could be engineered safely in Los Angeles

- Earthquakes were a challenge, not a barrier

- Fire, structural, and seismic risks could be managed

The height restriction was no longer about safety — it was about philosophy.

The Ironic Legacy

When Los Angeles finally lifted its height limit in 1957, the city did not suddenly erupt into skyscrapers. The habit of building outward was already deeply entrenched.

The result:

- A skyline that arrived decades late

- Uneven density across the region

- Multiple business centers instead of one core

- Housing and transit challenges baked into the city’s growth pattern

City Hall never triggered a skyscraper boom — but it quietly made one possible.

Why This Still Matters

Today, Los Angeles continues to wrestle with:

- Housing shortages

- Transit-oriented development debates

- Height and zoning battles near rail corridors

- Resistance to density in a growing city

These debates didn’t begin recently.

They trace back to a single contradiction: a city that banned tall buildings — while proving they could be built safely all along.

Los Angeles City Hall wasn’t just a monument.

It was a test case — and it passed.

Further Reading & Sources

- Los Angeles Department of City Planning – History of Urban Planning in LA

- Los Angeles Conservancy – History & Architecture of LA City Hall

- Water and Power Associates – Early Los Angeles Buildings & Height Limits

- USGS – How Buildings Are Designed to Withstand Earthquakes

- Los Angeles Department of Building and Safety – Building Code History

More from The Knowledge Series on STM Daily News

Discover more from Daily News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.