News

Colonialism’s legacy has left Caribbean nations much more vulnerable to hurricanes

Farah Nibbs, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

Long before colonialism brought slavery to the Caribbean, the native islanders saw hurricanes and storms as part of the normal cycle of life.

The Taino of the Greater Antilles and the Kalinago, or Caribs, of the Lesser Antilles developed systems that enabled them to live with storms and limit their exposure to damage.

On the larger islands, such as Jamaica and Cuba, the Taino practiced crop selection with storms in mind, preferring to plant root crops such as cassava or yucca with high resistance to damage from hurricane and storm winds, as Stuart Schwartz describes in his 2016 book “Sea of Storms.”

The Kalinago avoided building their settlements along the coast to limit storm surges and wind damage. The Calusa of southwest Florida used trees as windbreaks against storm winds.

In fact, it was the Kalinago and Taino who first taught the Europeans – primarily the British, Dutch, French and Spanish – about hurricanes and storms. Even the word ‘hurricane’ comes from Huracán, a Taino and Mayan word denoting the god of wind.

But then colonialism changed everything.

I study natural disasters in the Caribbean, including how history molded responses to disasters today.

The current disaster crisis that the Caribbean’s small islands are experiencing as hurricanes intensify did not start a few decades ago. Rather, the islands’ vulnerability is a direct result of the exploitative systems forced upon the region by colonialism, its legacies of slave-based land policies and ill-suited construction and development practices, and its environmental injustices.

Forcing people into harm’s way

The colonial powers changed how Caribbean people interacted with the land, where they lived and how they recovered from natural hazard events.

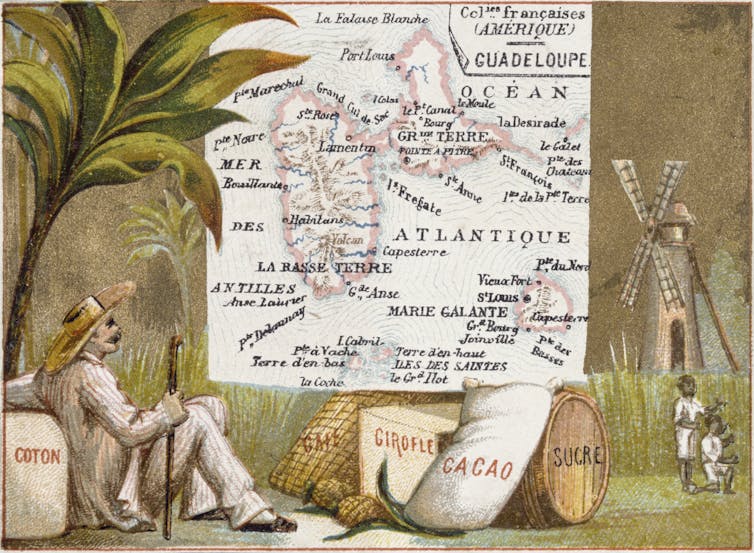

Rather than growing crops that could sustain the local food supply, the Europeans who began arriving in the 1600s focused on exploitative extractive economic models and export cash crops through the plantation economy.

They forced Indigenous people off their lands and built settlements along the coast, which made it easier to import enslaved peoples and goods and to export cash crops such as sugar and tobacco to Europe – and also left communities vulnerable to storms. They also developed settlements in low-lying areas, often near rivers and streams, which could provide transportation for agricultural produce but which became flood risks during heavy rains.

Today, more than 70% of the Caribbean’s population lives along the coast, often less than a mile from the shore. These coastlines are not only highly exposed to hurricanes but also to sea-level rise fueled by climate change.

Legacies of slave-based land policies

Colonialism’s legacy of land policies has also made recovery from disasters much harder today.

When colonial powers took over, a few landowners were given control of most of the land, while the majority of the population was forced onto marginal and small areas. The local population had no legal right to the land, as the people did not possess land certificate titles or deeds and were often forced to pay rent to landlords.

After independence, most island governments tried to acquire land from former plantations or estates and to redistribute it to the working class. But these efforts, mainly in the 1960s and ’70s, largely failed to transform land ownership, improve economic development or reduce vulnerability.

One colonial legacy perpetuating vulnerability to this day is known as crown land, or state land. In the English-speaking Caribbean, all land for which there was no land grant was considered property of the British crown. Crown land can be found in every English-speaking island to this day. https://www.youtube.com/embed/YTckM-cNeII?wmode=transparent&start=0 How colonial powers controlled the Caribbean over time.

For example, in Barbuda, all land is vested in the “crown in perpetuity” on behalf of Barbudans. This means that an individual born on the island of Barbuda cannot individually own land.

Instead, land is communally owned, which limits access to the credit and development opportunities that were sorely needed to reconstruct the island after Hurricane Maria in 2017. Most Barbudans were unable to insure their homes because they had no title deeds to their property.

This and other collective land tenure systems created by colonialism places Caribbean residents at greater risk from a variety of natural hazards and limits their ability to seek financial credit for disaster recovery today.

The roots of poor construction

Vulnerability to disasters in the Caribbean also has roots in post-slavery housing construction and subsequent failures to institute proper building codes.

After emancipation from slavery, freed people had no right nor access to land. To build houses, they were forced to lease land from the former enslavers who at a whim could terminate their employment or kick them off the land.

This led to the development of a particular type of housing structure known as chattel houses in countries such as Barbados. These houses are tiny and were constructed in a way in which they could be easily taken apart and loaded onto carts, should the residents be forced out by their former enslavers. Many Bajans still live in these houses today, although quite a few have been converted to restaurants or shops.

In Aruba, Bonaire and Curaçao, owned by the Dutch, slave huts were built along the coast, on land not suitable for agriculture and easily damaged by storms. These former slave huts are now tourist attractions, but the colonial patterns of settling along the coast has left many coastal communities exposed to hurricane damage and rising seas.

The vulnerability of such houses is not only a result of their exposure to natural hazards but also the underlying social structures.

In many islands today, poorer residents can’t afford protective measures, such as installing storm shutters or purchasing solar-powered generators.

They often live in marginal and disaster-prone areas, such as steep hillsides, where housing tends to be cheaper. Houses in these areas are also often poorly constructed with low-grade materials, such as galvanized sheeting for roofs and walls.

This situation is made worse by the informal and unregulated nature of residential housing construction in the region and the poor enforcement of building codes.

Due to the legacy of colonialism, most housing or building standards or codes in the Commonwealth Caribbean are relics from the United Kingdom and in the French Antilles from France. Building standards across the region lack uniformity and are generally subjective and uncontrolled. Financial limitations and staffing constraints mean that codes and standards more often than not remain unenforced.

Progress, but still a lot of work to do

The Caribbean has made progress in developing wind-related building codes to try to increase resilience in recent years. And while damage from torrential rain is still not properly addressed in most Caribbean building standards, scientific guidance is available through the Caribbean Institute for Meteorology and Hydrology in Barbados.

Individual islands, including Dominica and Saint Lucia, have new minimum building standards for recovery after disasters. The island of Grenada is hoping to guide new construction as it recovers from Hurricane Beryl. Trinidad and Tobago has developed a national land use strategy but has struggled to use it.

Construction standards can help the islands build resilience. But work remains to be done to overcome the legacy of colonial-era land policies and development that have left island towns vulnerable to increasing storm risks.

Farah Nibbs, Assistant Professor of Emergency and Disaster Health Systems, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The Bridge is a section of the STM Daily News Blog meant for diversity, offering real news stories about bona fide community efforts to perpetuate a greater good. The purpose of The Bridge is to connect the divides that separate us, fostering understanding and empathy among different groups. By highlighting positive initiatives and inspirational actions, The Bridge aims to create a sense of unity and shared purpose. This section brings to light stories of individuals and organizations working tirelessly to promote inclusivity, equality, and mutual respect. Through these narratives, readers are encouraged to appreciate the richness of diverse perspectives and to participate actively in building stronger, more cohesive communities.

https://stmdailynews.com/the-bridge

Discover more from Daily News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Long Track Back

Why Downtown Los Angeles Feels Small Compared to Other Cities

Downtown Los Angeles often feels “small” compared to other U.S. cities, but that’s only part of the story. With some of the tallest buildings west of the Mississippi and skyline clusters spread across the region, LA’s downtown reflects the city’s unique polycentric identity—one that, if combined, could form a true mega downtown.

Last Updated on February 18, 2026 by Daily News Staff

Panorama of Los Angeles from Mount Hollywood – California, United States

When people think of major American cities, they often imagine a bustling, concentrated downtown core filled with skyscrapers. New York has Manhattan, Chicago has the Loop, San Francisco has its Financial District. Los Angeles, by contrast, often leaves visitors surprised: “Is this really downtown?”

The answer is yes—and no.

Downtown LA in Context

Compared to other major cities, Downtown Los Angeles (DTLA) is relatively small as a central business district. For much of the 20th century, strict height restrictions capped most buildings under 150 feet, while cities like Chicago and New York were erecting early skyscrapers. LA’s skyline didn’t really begin to climb until the late 1960s.

But history alone doesn’t explain why DTLA feels different. The real story lies in how Los Angeles grew: not as one unified city center, but as a collection of many hubs.

![]()

Downtown Los Angeles

A Polycentric City

Los Angeles is famously decentralized. Hollywood developed around the film industry. Century City rose on former studio land as a business hub. Burbank became a studio and aerospace center. Long Beach grew around the port. The Wilshire Corridor filled with office towers and condos.

Unlike other cities where downtown is the place for work, culture, and finance, Los Angeles spread its energy outward. Freeways and car culture made it easy for businesses and residents to operate outside of downtown. The result is a polycentric metropolis, with multiple “downtowns” rather than one dominant core.

A Resident’s Perspective

As someone who lived in Los Angeles for 28 years, I see DTLA differently. While some outsiders describe it as “small,” the reality is that Downtown Los Angeles is still significant. It has some of the tallest buildings west of the Mississippi River, including the Wilshire Grand Center and the U.S. Bank Tower. Over the last two decades, adaptive reuse projects have transformed old office buildings into lofts, while developments like LA Live, Crypto.com Arena, and the Broad Museum have revitalized the area.

In other words, DTLA is large enough—it just plays a different role than downtowns in other American cities.

View of Westwood, Century City, Beverly Hills, and the Wilshire Corridor.

The “Mega Downtown” That Isn’t

A friend once put it to me with a bit of imagination: “If you could magically pick up all of LA’s skyline clusters—Downtown, Century City, Hollywood, the Wilshire Corridor—and drop them together in one spot, you’d have a mega downtown.”

He’s right. Los Angeles doesn’t lack tall buildings or urban energy—it just spreads them out over a vast area, reflecting the city’s unique history, geography, and culture.

A Downtown That Fits Its City

So, is Downtown LA “small”? Compared to Manhattan or Chicago’s Loop, yes. But judged on its own terms, DTLA is a vibrant hub within a much larger, decentralized metropolis. It’s a downtown that reflects Los Angeles itself: sprawling, diverse, and impossible to fit neatly into the mold of other American cities.

🔗 Related Links

Dive into “The Knowledge,” where curiosity meets clarity. This playlist, in collaboration with STMDailyNews.com, is designed for viewers who value historical accuracy and insightful learning. Our short videos, ranging from 30 seconds to a minute and a half, make complex subjects easy to grasp in no time. Covering everything from historical events to contemporary processes and entertainment, “The Knowledge” bridges the past with the present. In a world where information is abundant yet often misused, our series aims to guide you through the noise, preserving vital knowledge and truths that shape our lives today. Perfect for curious minds eager to discover the ‘why’ and ‘how’ of everything around us. Subscribe and join in as we explore the facts that matter. https://stmdailynews.com/the-knowledge/

Discover more from Daily News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Knowledge

Century City: From Hollywood Backlot to Business Hub

Century City, originally part of 20th Century Fox’s backlot, transformed into a prominent business district in Los Angeles during the 1950s amid the decline of cinema. Developer William Zeckendorf envisioned a mixed-use urban center, leading to iconic skyscrapers and establishing the area as a hub for law, finance, and media, blending Hollywood history with modern business.

Before Century City became one of Los Angeles’ premier business districts, it was part of 20th Century Fox’s sprawling backlot, used for filming movies and housing studio operations. By the 1950s, as television rose and movie attendance declined, 20th Century Fox faced financial challenges and decided to sell a portion of its land.

Developer William Zeckendorf envisioned a “city within a city”—a modern, mixed-use urban center with office towers, hotels, and entertainment facilities. Branded Century City, the name paid homage to its studio roots while symbolizing LA’s vision for the future.

The first skyscrapers, including the Gateway West Building, set the tone for the district’s sleek, futuristic skyline. Architects like Welton Becket and Minoru Yamasaki helped shape Century City’s iconic look. Over time, it evolved from Hollywood’s backlot to a corporate and legal hub, attracting law firms, financial institutions, and media companies.

Today, Century City stands as a testament to Los Angeles’ postwar optimism, westward expansion, and multi-centered urban growth—a unique blend of Hollywood history and modern business.

Related STM Daily News Links:

- The Evolution of Los Angeles Public Transportation

- Why Los Angeles Grew Into a Sprawling City

- Downtown Los Angeles: Past, Present, and Future

Dive into “The Knowledge,” where curiosity meets clarity. This playlist, in collaboration with STMDailyNews.com, is designed for viewers who value historical accuracy and insightful learning. Our short videos, ranging from 30 seconds to a minute and a half, make complex subjects easy to grasp in no time. Covering everything from historical events to contemporary processes and entertainment, “The Knowledge” bridges the past with the present. In a world where information is abundant yet often misused, our series aims to guide you through the noise, preserving vital knowledge and truths that shape our lives today. Perfect for curious minds eager to discover the ‘why’ and ‘how’ of everything around us. Subscribe and join in as we explore the facts that matter. https://stmdailynews.com/the-knowledge/

Discover more from Daily News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Community

Local governments provide proof that polarization is not inevitable

Local politics help mitigate national polarization by focusing on concrete issues like infrastructure and community needs rather than divisive symbolic debates. A survey indicates that local officials experience less partisanship, as interpersonal connections foster recognition of shared interests. This suggests that reducing polarization is possible through collaboration and changes in election laws.

Lauren Hall, Rochester Institute of Technology

When it comes to national politics, Americans are fiercely divided across a range of issues, including gun control, election security and vaccines. It’s not new for Republicans and Democrats to be at odds over issues, but things have reached a point where even the idea of compromising appears to be anathema, making it more difficult to solve thorny problems.

But things are much less heated at the local level. A survey of more than 1,400 local officials by the Carnegie Corporation and CivicPulse found that local governments are “largely insulated from the harshest effects of polarization.” Communities with fewer than 50,000 residents proved especially resilient to partisan dysfunction.

Why this difference? As a political scientist, I believe that lessons from the local level not only open a window onto how polarization works but also the dynamics and tools that can help reduce it.

Problems are more concrete

Local governments deal with concrete issues – sometimes literally, when it comes to paving roads and fixing potholes. In general, cities and counties handle day-to-day functions, such as garbage pickup, running schools and enforcing zoning rules. Addressing tangible needs keeps local leaders’ attention fixed on specific problems that call out for specific solutions, not lengthy ideological debates.

By contrast, a lot of national political conflict in the U.S. involves symbolic issues, such as debates about identity and values on topics such as race, abortion and transgender rights. These battles are often divisive, even more so than purely ideological disagreements, because they can activate tribal differences and prove more resistant to compromise.

Such arguments at the national level, or on social media, can lead to wildly inaccurate stereotypes about people with opposing views. Today’s partisans often perceive their opponents as far more extreme than they actually are, or they may stereotype them – imagining that all Republicans are wealthy, evangelical culture warriors, for instance, or conversely being convinced that all Democrats are radical urban activists. In terms of ideology, the median members of both parties, in fact, look similar.

These kinds of misperceptions can fuel hostility.

Local officials, however, live among the human beings they represent, whose complexity defies caricature. Living and interacting in the same communities leads to greater recognition of shared interests and values, according to the Carnegie/CivicPulse survey.

Meaningful interaction with others, including partisans of the opposing party, reduces prejudice about them. Local government provides a natural space where identities overlap.

People are complicated

In national U.S. politics today, large groups of individuals are divided not only by party but a variety of other factors, including race, religion, geography and social networks. When these differences align with ideology, political disagreement can feel like an existential threat.

Such differences are not always as pronounced at the local level. A neighbor who disagrees about property taxes could be the coach of your child’s soccer team. Your fellow school board member might share your concerns about curriculum but vote differently in presidential elections.

These cross-cutting connections remind us that political opponents are not a monolithic enemy but complex individuals. When people discover they have commonalities outside of politics with others holding opposing views, polarization can decrease significantly.

Finally, most local elections are technically nonpartisan. Keeping party labels off ballots allows voters to judge candidates as individuals and not merely as Republicans or Democrats.

National implications

None of this means local politics are utopian.

Like water, polarization tends to run downhill, from the national level to local contests, particularly in major cities where candidates for mayor and other office are more likely to run as partisans. Local governments also see culture war debates, notably in the area of public school instruction.

Nevertheless, the relative partisan calm of local governance suggests that polarization is not inevitable. It emerges from specific conditions that can be altered.

Polarization might be reduced by creating more opportunities for cross-partisan collaboration around concrete problems. Philanthropists and even states might invest in local journalism that covers pragmatic governance rather than partisan conflict. More cities and counties could adopt changes in election law that would de-emphasize party labels where they add little information for voters.

Aside from structural changes, individual Americans can strive to recognize that their neighbors are not the cardboard cutouts they might imagine when thinking about “the other side.” Instead, Americans can recognize that even political opponents are navigating similar landscapes of community, personal challenges and time constraints, with often similar desires to see their roads paved and their children well educated.

The conditions shaping our interactions matter enormously. If conditions change, perhaps less partisan rancor will be the result.

Lauren Hall, Associate professor of Political Science, Rochester Institute of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The Bridge is a section of the STM Daily News Blog meant for diversity, offering real news stories about bona fide community efforts to perpetuate a greater good. The purpose of The Bridge is to connect the divides that separate us, fostering understanding and empathy among different groups. By highlighting positive initiatives and inspirational actions, The Bridge aims to create a sense of unity and shared purpose. This section brings to light stories of individuals and organizations working tirelessly to promote inclusivity, equality, and mutual respect. Through these narratives, readers are encouraged to appreciate the richness of diverse perspectives and to participate actively in building stronger, more cohesive communities.

https://stmdailynews.com/the-bridge

Discover more from Daily News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.