Science

First contact with aliens could end in colonization and genocide if we don’t learn from history

David Delgado Shorter, University of California, Los Angeles; Kim TallBear, University of Alberta, and William Lempert, Bowdoin College

We’re only halfway through 2023, and it feels already like the year of alien contact.

In February, President Joe Biden gave orders to shoot down three unidentified aerial phenomena – NASA’s title for UFOs. Then, the alleged leaked footage from a Navy pilot of a UFO, and then news of a whistleblower’s report on a possible U.S. government cover-up about UFO research. Most recently, an independent analysis published in June suggests that UFOs might have been collected by a clandestine agency of the U.S. government.

If any actual evidence of extraterrestrial life emerges, whether from whistleblower testimony or an admission of a cover-up, humans would face a historic paradigm shift.

As members of an Indigenous studies working group who were asked to lend our disciplinary expertise to a workshop affiliated with the Berkeley SETI Research Center, we have studied centuries of culture contacts and their outcomes from around the globe. Our collaborative preparations for the workshop drew from transdisciplinary research in Australia, New Zealand, Africa and across the Americas.

In its final form, our group statement illustrated the need for diverse perspectives on the ethics of listening for alien life and a broadening of what defines “intelligence” and “life.” Based on our findings, we consider first contact less as an event and more as a long process that has already begun.

Who’s in charge of first contact

The question of who is “in charge” of preparing for contact with alien life immediately comes to mind. The communities – and their interpretive lenses – most likely to engage in any contact scenario would be military, corporate and scientific.

By giving Americans the legal right to profit from space tourism and planetary resource extraction, the Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act of 2015 could mean that corporations will be the first to find signs of extraterrestrial societies. Otherwise, while detecting unidentified aerial phenomena is usually a military matter, and NASA takes the lead on sending messages from Earth, most activities around extraterrestrial communications and evidence fall to a program called SETI, or the search for extraterrestrial intelligence.

SETI is a collection of scientists with a variety of research endeavors, including Breakthrough Listen, which listens for “technosignatures,” or markers, like pollutants, of a designed technology.

SETI investigators are virtually always STEM – science, technology, engineering and math – scholars. Few in the social science and humanities fields have been afforded opportunities to contribute to concepts of and preparations for contact.

In a promising act of disciplinary inclusion, the Berkeley SETI Research Center in 2018 invited working groups – including our Indigenous studies working group – from outside STEM fields to craft perspective papers for SETI scientists to consider.

Ethics of listening

Neither Breakthough Listen nor SETI’s site features a current statement of ethics beyond a commitment to transparency. Our working group was not the first to raise this issue. And while the SETI Institute and certain research centers have included ethics in their event programming, it seems relevant to ask who NASA and SETI answer to, and what ethical guidelines they’re following for a potential first contact scenario.

SETI’s Post-Detection Hub – another rare exception to SETI’s STEM-centrism – seems the most likely to develop a range of contact scenarios. The possible circumstances imagined include finding ET artifacts, detecting signals from thousands of light years away, dealing with linguistic incompatibility, finding microbial organisms in space or on other planets, and biological contamination of either their or our species. Whether the U.S. government or heads of military would heed these scenarios is another matter.

SETI-affiliated scholars tend to reassure critics that the intentions of those listening for technosignatures are benevolent, since “what harm could come from simply listening?” The chair emeritus of SETI Research, Jill Tarter, defended listening because any ET civilization would perceive our listening techniques as immature or elementary.

But our working group drew upon the history of colonial contacts to show the dangers of thinking that whole civilizations are comparatively advanced or intelligent. For example, when Christopher Columbus and other European explorers came to the Americas, those relationships were shaped by the preconceived notion that the “Indians” were less advanced due to their lack of writing. This led to decades of Indigenous servitude in the Americas.

The working group statement also suggested that the act of listening is itself already within a “phase of contact.” Like colonialism itself, contact might best be thought of as a series of events that starts with planning, rather than a singular event. Seen this way, isn’t listening potentially without permission just another form of surveillance? To listen intently but indiscriminately seemed to our working group like a type of eavesdropping.

It seems contradictory that we begin our relations with aliens by listening in without their permission while actively working to stop other countries from listening to certain U.S. communications. If humans are initially perceived as disrespectful or careless, ET contact could more likely lead to their colonization of us.

Histories of contact

Throughout histories of Western colonization, even in those few cases when contactees were intended to be protected, contact has led to brutal violence, pandemics, enslavement and genocide.

James Cook’s 1768 voyage on the HMS Endeavor was initiated by the Royal Society. This prestigious British academic society charged him with calculating the solar distance between the Earth and the Sun by measuring the visible movement of Venus across the Sun from Tahiti. The society strictly forbade him from any colonial engagements.

Though he achieved his scientific goals, Cook also received orders from the Crown to map and claim as much territory as possible on the return voyage. Cook’s actions put into motion wide-scale colonization and Indigenous dispossession across Oceania, including the violent conquests of Australia and New Zealand.

The Royal Society gave Cook a “prime directive” of doing no harm and to only conduct research that would broadly benefit humanity. However, explorers are rarely independent from their funders, and their explorations reflect the political contexts of their time.

As scholars attuned to both research ethics and histories of colonialism, we wrote about Cook in our working group statement to showcase why SETI might want to explicitly disentangle their intentions from those of corporations, the military and the government.

Although separated by vast time and space, both Cook’s voyage and SETI share key qualities, including their appeal to celestial science in the service of all humanity. They also share a mismatch between their ethical protocols and the likely long-term impacts of their success. https://www.youtube.com/embed/5gZwLGrJQrM?wmode=transparent&start=0 This BBC video describes the modern ramifications of Captain James Cook’s colonial legacy in New Zealand.

The initial domino of a public ET message, or recovered bodies or ships, could initiate cascading events, including military actions, corporate resource mining and perhaps even geopolitical reorganizing. The history of imperialism and colonialism on Earth illustrates that not everyone benefits from colonization. No one can know for sure how engagement with extraterrestrials would go, though it’s better to consider cautionary tales from Earth’s own history sooner rather than later.

This article has been updated to correct the date of James Cook’s voyage.

David Delgado Shorter, Professor of World Arts and Cultures/Dance, University of California, Los Angeles; Kim TallBear, Professor of Native Studies, University of Alberta, and William Lempert, Assistant Professor of Anthropology, Bowdoin College

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The science section of our news blog STM Daily News provides readers with captivating and up-to-date information on the latest scientific discoveries, breakthroughs, and innovations across various fields. We offer engaging and accessible content, ensuring that readers with different levels of scientific knowledge can stay informed. Whether it’s exploring advancements in medicine, astronomy, technology, or environmental sciences, our science section strives to shed light on the intriguing world of scientific exploration and its profound impact on our daily lives. From thought-provoking articles to informative interviews with experts in the field, STM Daily News Science offers a harmonious blend of factual reporting, analysis, and exploration, making it a go-to source for science enthusiasts and curious minds alike. https://stmdailynews.com/category/science/

Discover more from Daily News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

unknown

Why people tend to believe UFOs are extraterrestrial

Last Updated on March 13, 2026 by Daily News Staff

Barry Markovsky, University of South Carolina

Most of us still call them UFOs – unidentified flying objects. NASA recently adopted the term “unidentified anomalous phenomena,” or UAP. Either way, every few years popular claims resurface that these things are not of our world, or that the U.S. government has some stored away.

I’m a sociologist who focuses on the interplay between individuals and groups, especially concerning shared beliefs and misconceptions. As for why UFOs and their alleged occupants enthrall the public, I’ve found that normal human perceptual and social processes explain UFO buzz as much as anything up in the sky.

Historical context

Like political scandals and high-waisted jeans, UFOs trend in and out of collective awareness but never fully disappear. Thirty years of polling find that 25%-50% of surveyed Americans believe at least some UFOs are alien spacecraft. Today in the U.S., over 100 million adults think our galactic neighbors pay us visits.

It wasn’t always so. Linking objects in the sky with visiting extraterrestrials has risen in popularity only in the past 75 years. Some of this is probably market-driven. Early UFO stories boosted newspaper and magazine sales, and today they are reliable clickbait online.

In 1980, a popular book called “The Roswell Incident” by Charles Berlitz and William L. Moore described an alleged flying saucer crash and government cover-up 33 years prior near Roswell, New Mexico. The only evidence ever to emerge from this story was a small string of downed weather balloons. Nevertheless, the book coincided with a resurgence of interest in UFOs. From there, a steady stream of UFO-themed TV shows, films, and pseudo-documentaries has fueled public interest. Perhaps inevitably, conspiracy theories about government cover-ups have risen in parallel.

Some UFO cases inevitably remain unresolved. But despite the growing interest, multiple investigations have found no evidence that UFOs are of extraterrestrial origin – other than the occasional meteor or misidentification of Venus.

But the U.S. Navy’s 2017 Gimbal video continues to appear in the media. It shows strange objects filmed by fighter jets, often interpreted as evidence of alien spacecraft. And in June 2023, an otherwise credible Air Force veteran and former intelligence officer made the stunning claim that the U.S. government is storing numerous downed alien spacecraft and their dead occupants. https://www.youtube.com/embed/2TumprpOwHY?wmode=transparent&start=0 UFO videos released by the U.S. Navy, often taken as evidence of alien spaceships.

Human factors contributing to UFO beliefs

Only a small percentage of UFO believers are eyewitnesses. The rest base their opinions on eerie images and videos strewn across both social media and traditional mass media. There are astronomical and biological reasons to be skeptical of UFO claims. But less often discussed are the psychological and social factors that bring them to the popular forefront.

Many people would love to know whether or not we’re alone in the universe. But so far, the evidence on UFO origins is ambiguous at best. Being averse to ambiguity, people want answers. However, being highly motivated to find those answers can bias judgments. People are more likely to accept weak evidence or fall prey to optical illusions if they support preexisting beliefs.

For example, in the 2017 Navy video, the UFO appears as a cylindrical aircraft moving rapidly over the background, rotating and darting in a manner unlike any terrestrial machine. Science writer Mick West’s analysis challenged this interpretation using data displayed on the tracking screen and some basic geometry. He explained how the movements attributed to the blurry UFO are an illusion. They stem from the plane’s trajectory relative to the object, the quick adjustments of the belly-mounted camera, and misperceptions based on our tendency to assume cameras and backgrounds are stationary.

West found the UFO’s flight characteristics were more like a bird’s or a weather balloon’s than an acrobatic interstellar spacecraft. But the illusion is compelling, especially with the Navy’s still deeming the object unidentified.

West also addressed the former intelligence officer’s claim that the U.S. government possesses crashed UFOs and dead aliens. He emphasized caution, given the whistleblower’s only evidence was that people he trusted told him they’d seen the alien artifacts. West noted we’ve heard this sort of thing before, along with promises that the proof will soon be revealed. But it never comes.

Anyone, including pilots and intelligence officers, can be socially influenced to see things that aren’t there. Research shows that hearing from others who claim to have seen something extraordinary is enough to induce similar judgments. The effect is heightened when the influencers are numerous or higher in status. Even recognized experts aren’t immune from misjudging unfamiliar images obtained under unusual conditions.

Group factors contributing to UFO beliefs

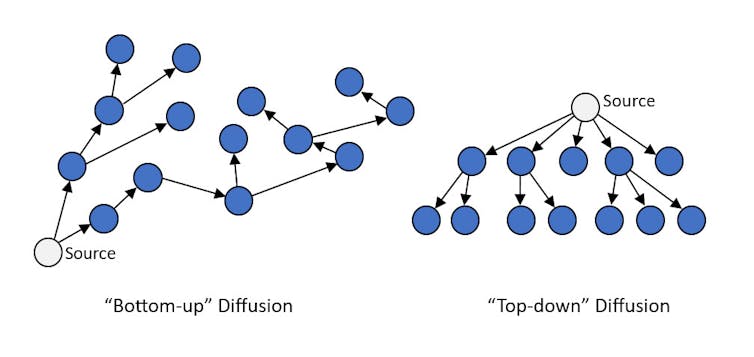

“Pics or it didn’t happen” is a popular expression on social media. True to form, users are posting countless shaky images and videos of UFOs. Usually they’re nondescript lights in the sky captured on cellphone cameras. But they can go viral on social media and reach millions of users. With no higher authority or organization propelling the content, social scientists call this a bottom-up social diffusion process.

In contrast, top-down diffusion occurs when information emanates from centralized agents or organizations. In the case of UFOs, sources have included social institutions like the military, individuals with large public platforms like U.S. senators, and major media outlets like CBS.

Amateur organizations also promote active personal involvement for many thousands of members, the Mutual UFO Network being among the oldest and largest. But as Sharon A. Hill points out in her book “Scientifical Americans,” these groups apply questionable standards, spread misinformation and garner little respect within mainstream scientific communities.

Top-down and bottom-up diffusion processes can combine into self-reinforcing loops. Mass media spreads UFO content and piques worldwide interest in UFOs. More people aim their cameras at the skies, creating more opportunities to capture and share odd-looking content. Poorly documented UFO pics and videos spread on social media, leading media outlets to grab and republish the most intriguing. Whistleblowers emerge periodically, fanning the flames with claims of secret evidence.

Despite the hoopla, nothing ever comes of it.

For a scientist familiar with the issues, skepticism that UFOs carry alien beings is wholly separate from the prospect of intelligent life elsewhere in the universe. Scientists engaged in the search for extraterrestrial intelligence have a number of ongoing research projects designed to detect signs of extraterrestrial life. If intelligent life is out there, they’ll likely be the first to know.

As astronomer Carl Sagan wrote, “The universe is a pretty big place. If it’s just us, seems like an awful waste of space.”

Barry Markovsky, Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Sociology, University of South Carolina

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The science section of our news blog STM Daily News provides readers with captivating and up-to-date information on the latest scientific discoveries, breakthroughs, and innovations across various fields. We offer engaging and accessible content, ensuring that readers with different levels of scientific knowledge can stay informed. Whether it’s exploring advancements in medicine, astronomy, technology, or environmental sciences, our science section strives to shed light on the intriguing world of scientific exploration and its profound impact on our daily lives. From thought-provoking articles to informative interviews with experts in the field, STM Daily News Science offers a harmonious blend of factual reporting, analysis, and exploration, making it a go-to source for science enthusiasts and curious minds alike. https://stmdailynews.com/category/science/

Discover more from Daily News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

unknown

The Unfavorable Semicircle Mystery: The YouTube Channel That Uploaded Tens of Thousands of Cryptic Videos

In 2015, the YouTube channel Unfavorable Semicircle gained attention for its enigmatic and abundant video uploads, totaling over 70,000 before its deletion in 2016. Theories about its purpose vary, from automated content generation to digital art experimentation, leaving its intent unresolved.

In the vast digital landscape of the internet, strange phenomena occasionally emerge that leave investigators, tech enthusiasts, and everyday viewers scratching their heads. One of the most puzzling cases appeared in 2015, when a mysterious YouTube channel called Unfavorable Semicircle began uploading an astonishing number of cryptic videos.

Within months, the channel had published tens of thousands of bizarre clips, many of which seemed random, incomprehensible, and visually chaotic. But as internet detectives began analyzing the content more closely, they discovered that these videos might not have been random at all.

The Sudden Appearance of an Internet Mystery

The Unfavorable Semicircle channel reportedly appeared in March 2015, with its first uploads arriving in early April.

Almost immediately, the channel began publishing videos at an incredible pace. Observers estimated that the account uploaded thousands of videos per week, sometimes multiple videos per minute. By the time the channel disappeared in early 2016, researchers believed it had uploaded well over 70,000 videos, possibly far more.

The scale alone made the project seem impossible for a human to manage manually.

Strange Visuals and Cryptic Titles

Most of the videos shared similar characteristics:

- Extremely short or very long runtime

- Abstract visuals such as flashing colors, static, or distorted imagery

- Little or no audio, or heavily distorted sounds

- Titles made of random characters, symbols, or numbers

To casual viewers, the videos looked like pure digital noise. However, online investigators suspected something more deliberate was happening.

Hidden Images Discovered

The mystery deepened when researchers began extracting individual frames from some videos.

When thousands of frames from certain clips were stitched together, the results sometimes formed coherent images. One of the most famous examples involved a video titled “LOCK.” While the footage appeared chaotic at first, combining the frames revealed a recognizable composite image.

This discovery suggested the videos were carefully constructed rather than random uploads.

Theories About the Channel’s Purpose

Because the creator never explained the project, several theories emerged across Reddit, YouTube, and internet forums.

Automated Experiment

Many believe the channel was created using automated software that generated and uploaded content at scale.

Alternate Reality Game (ARG)

Some viewers suspected the channel might be part of a hidden puzzle or digital scavenger hunt.

Encrypted Communication

Others compared the channel to Cold War “numbers stations,” suggesting the videos could contain coded messages.

Digital Art Project

Another theory suggests the channel was an experimental art project exploring algorithms, data, and visual noise.

Despite years of investigation, no single explanation has been confirmed.

Why the Channel Disappeared

In February 2016, YouTube removed the channel, reportedly due to spam or automated activity violations.

By that time, the channel had already become a minor internet legend. Fortunately, some researchers managed to archive a large portion of the videos before they disappeared.

Even today, archived clips continue to circulate online as investigators attempt to decode them.

Other Mysterious YouTube Channels

The Unfavorable Semicircle mystery is not the only strange case on YouTube.

One well-known example is Webdriver Torso, a channel that uploaded hundreds of thousands of videos showing red and blue rectangles with simple beeping sounds. Internet speculation ran wild before Google eventually confirmed it was an internal YouTube testing account.

Another example is AETBX, which posts distorted visuals and unusual audio that some viewers believe contain hidden patterns or encoded information.

These cases highlight how automation, experimentation, and creativity can sometimes blur the line between technology and mystery.

A Digital Mystery That Remains Unsolved

Nearly a decade later, the true purpose behind Unfavorable Semicircle remains unknown.

Was it a sophisticated experiment? A piece of algorithmic art? Or simply an automated test that accidentally captured the internet’s imagination?

Whatever the explanation, the channel stands as a reminder that even in a world filled with billions of videos and endless information, the internet can still produce mysteries that challenge our understanding of technology.

Why Internet Mysteries Still Fascinate Us

Stories like Unfavorable Semicircle capture attention because they combine technology, creativity, and the unknown. They invite people from around the world to collaborate, analyze patterns, and search for meaning hidden in the noise.

And sometimes, the most intriguing part of the mystery is that the answer may never fully be known.

Related Coverage & Further Reading

- Atlas Obscura – The Unsettling Mystery of the Creepiest Channel on YouTube

- Her Campus – Top 5 Most Obscure Internet Mysteries

- Medium – Unfavorable Semicircle: The YouTube Mystery No One Can Solve

- Gazette Review – Top 10 Strangest YouTube Channels Ever

- Decoding the Unknown – Unfavorable Semicircle YouTube Mystery Archive

- Wikipedia – Unfavorable Semicircle

Dive into “The Knowledge,” where curiosity meets clarity. This playlist, in collaboration with STMDailyNews.com, is designed for viewers who value historical accuracy and insightful learning. Our short videos, ranging from 30 seconds to a minute and a half, make complex subjects easy to grasp in no time. Covering everything from historical events to contemporary processes and entertainment, “The Knowledge” bridges the past with the present. In a world where information is abundant yet often misused, our series aims to guide you through the noise, preserving vital knowledge and truths that shape our lives today. Perfect for curious minds eager to discover the ‘why’ and ‘how’ of everything around us. Subscribe and join in as we explore the facts that matter. https://stmdailynews.com/the-knowledge/

Discover more from Daily News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Knowledge

2025 was hotter than it should have been – 5 influences and a dirty surprise offer clues to what’s ahead

The past three years recorded unprecedented global heat, with 2025 being particularly warm. Factors such as greenhouse gas emissions and a decline in solar activity influenced temperatures and extreme weather patterns.

Michael Wysession, Washington University in St. Louis

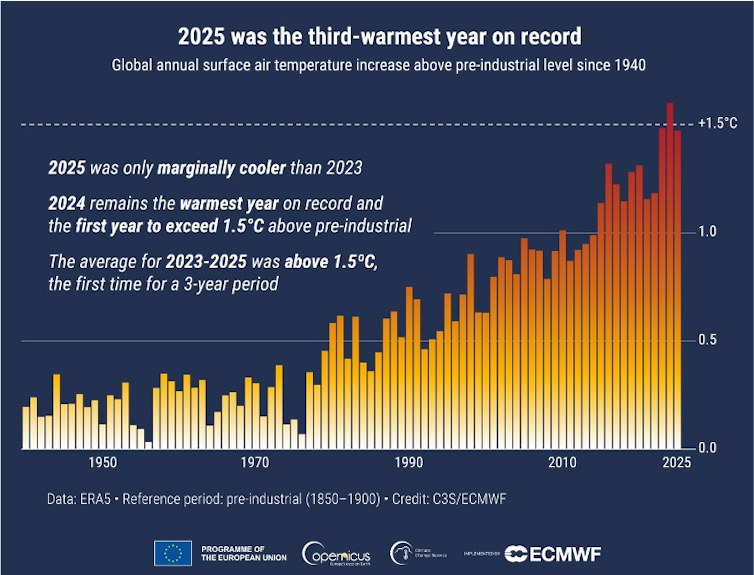

The past three years have been the world’s hottest on record by far, with 2025 almost tied with 2023 for second place. With that energy came extreme weather, from flash flooding to powerful hurricanes and severe droughts. Yet, by most indicators, the planet should have been cooler in 2025 than it was.

So, what happened, and what does that say about the year ahead?

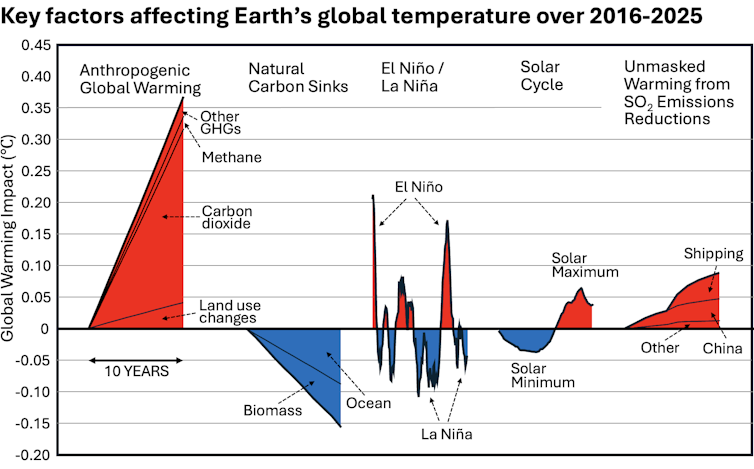

As an earth and environmental scientist, I study influences that affect global temperatures year to year, such as El Niño, wildfires and solar cycles. Some make Earth hotter. Some make it cooler. And one particularly unhealthy influence has been quietly hiding a large amount of global warming – until now.

Factors that made 2025 cooler than 2024

The Earth’s climate is the result of many factors that change from year to year. Some that helped make 2025 cooler than 2024 include:

La Niña’s arrival: La Niña is part of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, a natural climate pattern that fluctuates between warm El Niño conditions and cooler La Niña conditions. During El Niño, the Pacific Ocean heats up along the equator, influencing the atmosphere in ways that can cause intense storms, droughts and heat waves around the planet. La Niña does the opposite; it’s like putting an ice pack on the atmosphere.

Both 2023 and 2024 were El Niño years, but in 2025 conditions shifted to neutral and then to La Niña starting in September.

The solar cycle: The Sun reached its solar maximum near the end of 2024, the peak of its energy output in an approximately 11-year cycle, and began declining in 2025. So, while the sun’s output was still stronger than average in 2025, it was less than in 2024.

Fewer wildfires: Despite some destructive blazes, the world also saw fewer wildfires during 2025 than 2024, which put less carbon dioxide – a planet-warming greenhouse gas – into the atmosphere.

Despite those points, 2025 still ended up as the third-hottest year in over 175 years of record-keeping and likely one of the warmest in at least several thousand years. It was nearly as warm as 2023, at 2.6 degrees Fahrenheit (1.47 Celsius) above the 1850-1900 average, according to the European Union’s Copernicus Climate Change Service. It also had the second-highest average land temperature recorded, up 3.6 F (2 C) compared to preindustrial years, with more than 10% of the land experiencing record-high temperatures.

Factors that made 2025 warmer than expected

Several other factors made 2025 warmer than expected, and some are likely to continue to increase in 2026. They include:

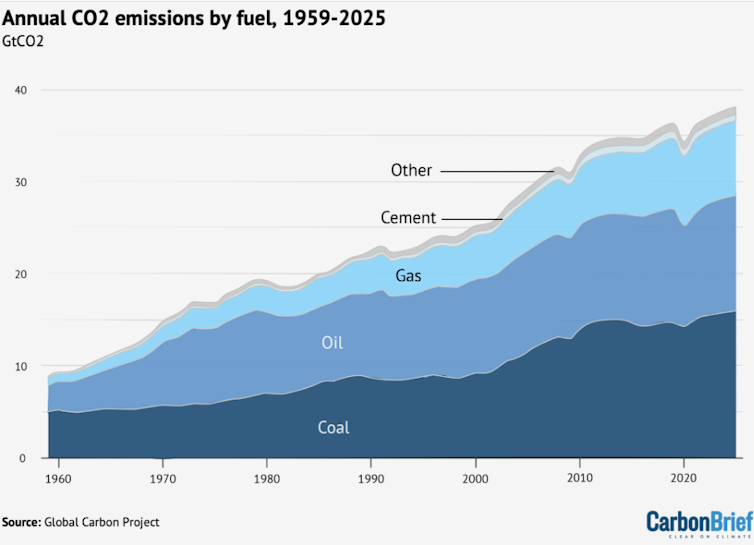

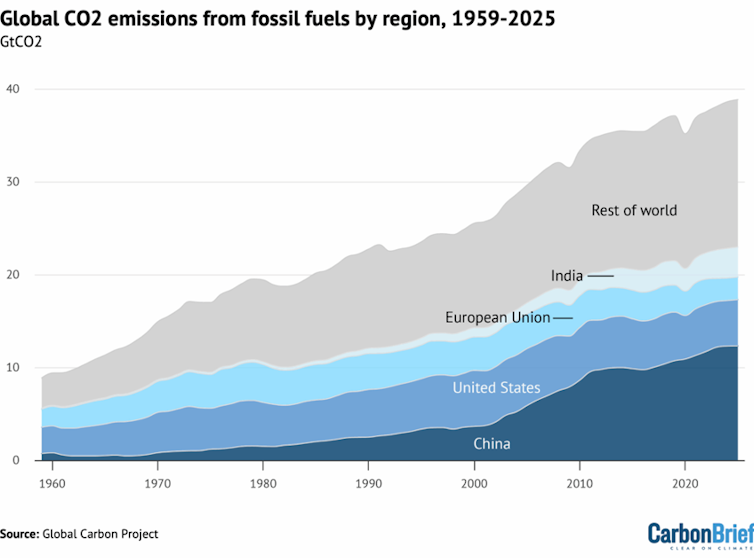

Greenhouse gas emissions: The big driver of global warming is excess greenhouse gas emissions, largely from burning fossil fuels, and 2025 had plenty.

Greenhouse gases trap heat near Earth’s surface like a blanket, raising the temperature. They also linger in the atmosphere for years to centuries, meaning gases released today will continue to warm the planet well into the future. The levels of carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide in the atmosphere all increased in 2025.

Rising energy demand drove an increase in fossil fuel use. About 80% of the increasing electric power demand came from emerging economies, largely for rising air conditioning demands as the world gets hotter. In the U.S., the rapid growth of data centers for AI and cryptocurrency mining helped boost U.S. carbon dioxide emissions by 2.4%.

Earth’s energy imbalance: Other sources can disrupt the natural balance between the amount of sunlight that reaches Earth and the lesser amount radiated back to space. A recent study found that Earth’s energy uptake surged and temperatures rose quickly when a rare three-year La Niña in 2020-2022 shifted to El Niño in 2023-2024.

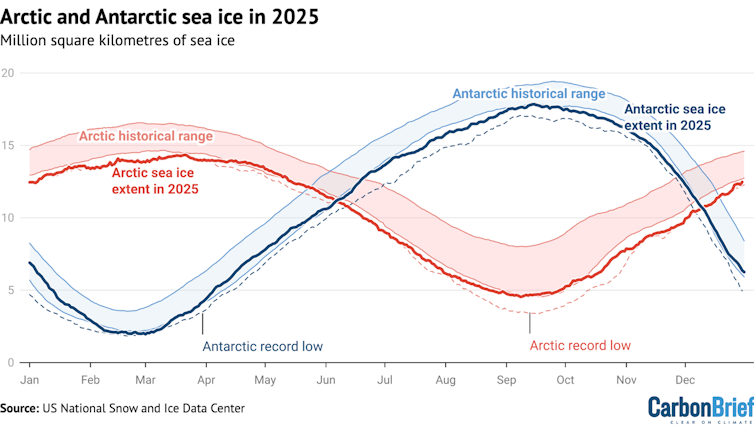

Declining polar ice, which efficiently reflects sunlight back into space, also affects the energy balance. As sea ice declines, it leaves dark ocean water that absorbs most of the sunlight that reaches it. In a spiraling feedback, warmer water melts sea ice, allowing more sunlight into the ocean, warming it faster; 2025 had the lowest winter peak of Arctic sea ice on record and the third-lowest minimum extent of Antarctic ice.

https://datawrapper.dwcdn.net/t0SSd/1

Air pollution: Sulfate aerosol pollution from coal combustion and burning heavy fuel oil in shipping has also been affecting Earth’s energy balance. It has been masking the full effects of human-caused greenhouse gases for years by reflecting sunlight back into space, creating a cooling effect. But sulfate aerosol pollution is also a serious health hazard, blamed for about 8 million human deaths per year from lung diseases.

Recent reductions in sulfate pollution – now 40% less than 20 years ago – have meant about a 0.2 F (0.13 C) increase in global temperatures. Much of the reduction was from China’s efforts to reduce its notoriously bad air pollution in recent years and international shipping rules in effect since 2020 that have reduced sulfur emissions from large ships by 85%.

Taking all factors together, humans are now warming the planet at a faster rate than at any point in human history: at about 0.5 F (0.27 C) per decade. That extra heat can fuel extreme weather, including flash floods, heat waves, extended droughts, wildfires and coastal flooding, affecting human lives and economies.

Predictions for 2026

Most climate models predict 2026 will be about as hot as 2025, depending on whether a Pacific El Niño develops, which forecasters give about a 60% chance of happening. The planet is already starting the year out warm, even if it doesn’t feel like that everywhere. While January was very cold in parts of the U.S., globally, Earth saw its fifth-warmest January on record, and much of the western U.S. saw one of its warmest winters on record.

Solar output will continue to decrease slowly in 2026. However, the International Monetary Fund projects strong global economic growth at about 3.3%, suggesting electricity demand will also continue to grow. The International Energy Agency expects global electricity demand to increase by 3.6% per year through at least 2030.

Even though global renewable energy use is growing quickly, it isn’t growing fast enough to meet rising demand, meaning more fossil fuel use in the coming years. More fossil fuels burned means more emissions and more warming, while the ability of the ocean and land to absorb carbon dioxide continues to decrease. As a result, the atmosphere and oceans heat up, increasing the risks of passing tipping points – glaciers disappear, Atlantic Ocean circulation shuts down, permafrost thaws, coral reefs die.

If greenhouse gas emissions continue at a high rate, humanity may look back at 2025 as one the coolest years globally in the rest of our lives.

Michael Wysession, Professor of Earth, Environmental, and Planetary Sciences, Washington University in St. Louis

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Dive into “The Knowledge,” where curiosity meets clarity. This playlist, in collaboration with STMDailyNews.com, is designed for viewers who value historical accuracy and insightful learning. Our short videos, ranging from 30 seconds to a minute and a half, make complex subjects easy to grasp in no time. Covering everything from historical events to contemporary processes and entertainment, “The Knowledge” bridges the past with the present. In a world where information is abundant yet often misused, our series aims to guide you through the noise, preserving vital knowledge and truths that shape our lives today. Perfect for curious minds eager to discover the ‘why’ and ‘how’ of everything around us. Subscribe and join in as we explore the facts that matter. https://stmdailynews.com/the-knowledge/

Discover more from Daily News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.