actors & performers

Legendary Performer and Civil Rights Activist Harry Belafonte Dies at Age 96

Beloved performer and civil rights activist Harry Belafonte passed away at age 96 due to congestive heart failure. His legacy includes pioneering Caribbean music in the 1950s and being an important voice in the civil rights movement of the 60s.

Last Updated on September 20, 2025 by Daily News Staff

The world of music and activism has lost an icon as legendary performer Harry Belafonte passed away on Tuesday at the age of 96. His spokesman confirmed that he died of congestive heart failure.

Belafonte was a pioneer in the music industry, credited with launching the craze for Caribbean music in the 1950s. His music was a blend of calypso, jazz, and folk, which made him a beloved figure of his time. He won several awards for his Broadway performances and was also a popular actor, appearing in several films and TV shows.

However, his influence extended far beyond the entertainment industry. Belafonte was an important voice in the civil rights movement of the 1960s. He was a close friend of Martin Luther King Jr. and played a significant role in the movement’s success. He participated in numerous protests and rallies, using his platform to advocate for social justice and equality.

Belafonte’s activism didn’t stop there. He was also a strong advocate for humanitarian causes, including the fight against poverty and HIV/AIDS. He served as a UNICEF Goodwill Ambassador and helped raise awareness and funds for various causes.

Belafonte’s legacy is one of music, activism, and humanitarianism. He used his platform to bring attention to important issues and inspire change. He will be remembered as one of the greatest performers of his time and a true icon of social justice.

As the world mourns the loss of Harry Belafonte, his music and activism will continue to inspire future generations to make a positive impact on the world around them.

Discover more from Daily News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Entertainment

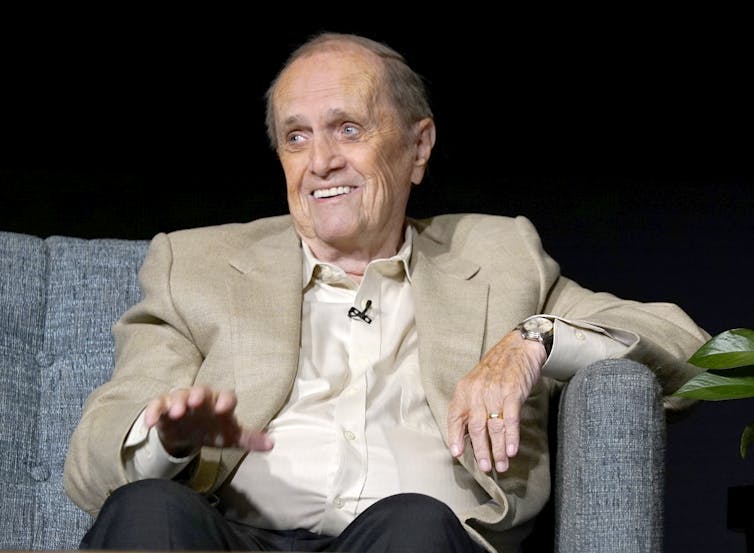

Bob Newhart was more than an actor or comedian – he was a literary master

Bob Newhart, initially a stand-up comic, used literary techniques in his routines, earning the Mark Twain Prize. His one-sided conversations engaged and entertained audiences.

Last Updated on March 8, 2026 by Daily News Staff

Mark Canada, Indiana University Kokomo

If you knew Bob Newhart only as an actor – most notably as the star of the legendary “Bob Newhart Show” but also in a minor though memorable role in the movie “Elf” – you may not have thought of him as a literary figure.

However, Newhart, who died on July 18, 2024, at the age of 94, began his rise to stardom as a stand-up comic, crafting and delivering such brilliant monologues as “Driving Instructor” and “Bus Drivers School.” In those bits, he demonstrated a mastery of diction, dialect, character and dialogue worthy of the title “literary master.”

In my view, there is perhaps no more fitting recipient of the Mark Twain Prize than Newhart, who received it in 2002.

As a literary scholar, I typically study traditional poetry and fiction by canonical authors such as Twain and Edgar Allan Poe. But the mastery of language and character is not the sole possession of poets and novelists. Newhart demonstrated that stand-up comedy could also be an art form. https://www.youtube.com/embed/8KSUSk2-JXc?wmode=transparent&start=0 Bob Newhart accepts the Mark Twain Prize in 2002.

‘The old humble bit’

One of his masterpieces is his “Abe Lincoln vs. Madison Avenue” stand-up routine, built around a quirky but timely premise.

Having witnessed the rise of advertising and public relations in the 1950s and 1960s, Newhart imagined a scenario from an earlier age. What if, he asked, there had been no real man with the mind and stature of Abraham Lincoln during America’s Civil War?

The advertising industry, he goes on to say, “would have had to create a Lincoln.” He then performs a one-sided imaginary telephone conversation between a press agent and someone employed to play the part of this manufactured Lincoln – introducing it with a line that would become iconic for Newhart, saying the conversation would have gone “something like this.”

The “something” that ensues is a tightly crafted, six-minute routine worthy of the term “poem.” Indeed, Newhart deployed some of the same literary devices wielded by previous masters such as Twain and Alexander Pope.

Like Twain, Newhart had a marvelous ear for dialect and seasoned his monologue with little bits of slang and jargon to capture the breezy speech of a stereotypical press agent.

“Hi, Abe, sweetheart, how are you, kid?” he begins. “How’s Gettysburg?”

Delivered quickly and offhandedly, the lines, like so much of Newhart’s stand-up work, are subtle, but effective – dead on without being too on the nose. Throughout the bit, he deploys similar little touches of diction – as when the agent refers to “Four score and seven,” the famous first words of the Gettysburg Address, as a “grabber.”

Herein lies another, even more effective, source of humor. Lincoln’s opening is famously lyrical and formal, the epitome of elocutionary eloquence, and the agent has reduced it to a “grabber.” This kind of deflation echoes an old satirical genre known as the “mock-epic.” As practiced by the Enlightment-era English poet, translator and satirist Alexander Pope and others, it draws its humor from the contrast between the sublime and the mundane or even ridiculous.

Newhart returns to the device when he has the agent try to explain to the made-up Abe the logic behind the line “The world will little note, nor long remember.”

Lincoln’s original line is graceful, alliterative and nearly perfectly iambic – an oratory gem if there ever was one – but, for the agent, it’s simply “the old humble bit.” https://www.youtube.com/embed/HTG3glnwoKE?wmode=transparent&start=0 Bob Newhart performs ‘Abe Lincoln vs. Madison Avenue.’

Character is key

Master writers of humor or, for that matter, fiction in general, will tell you that character is key. Get the characters right, and humor – or drama – will follow.

With more of his delightfully subtle touches, Newhart paints a hilarious picture of the naive bumbler the agency has to craft into a Lincoln. Again, as is often the case with humor, irony helps to achieve the desired effect – in this case, humor.

Lincoln was an eloquent, noble figure. He was larger than life – and certainly larger than this dimwit, who doesn’t even get the joke when one of the agency’s “gag writers” supposedly dashes off a line on Gen. Ulysses S. Grant.

The agent shares it with the fake Abe, saying, “They got a beautiful squelch on Grant. The next time they bug ya about Grant’s drinkin’ … you tell ’em you’re gonna find out what brand he drinks and send a case of it to all your other generals.”

After a short pause, the agent says, with Newhart’s famous stammer, “Uh, no, no, it’s, it’s like, like the brand, uh, was the reason he won.” Finally, after another short pause, the exasperated agent snaps, “… use it, it’s funny.” https://www.youtube.com/embed/XaUYQZR-y7I?wmode=transparent&start=0 Bob Newhart performs ‘Driving Instructor.’

Give the audience credit

This last “exchange” demonstrates the most ingenious aspect of Newhart’s humor: his signature one-sided conversation, which he also used to hilarious effect in “Driving Instructor” and other routines.

Now you know why the opening sequence of “The Bob Newhart Show” has Newhart answering a phone – an homage to his then-famous stand-up gag.

We never hear the voice of “Abe” but rather hear only the agent’s side of the conversation. It might seem like a minor detail, but this artifice means that we as the audience have to play an active role in the comedy. We hear the agent’s side and have to imagine what he is hearing. Sometimes the agent repeats what he supposedly hears, but, in this instance, when the agent is trying to explain the punchline of the Grant joke, the burden is on us.

Here again Newhart was employing an old device. In a dramatic monologue such as Robert Browning’s serious poem “My Last Duchess,” the poet leaves out key details, forcing us to detect them and complete the only partially told story.

The device is especially effective in comedy because, as Newhart knew on some level, we all like to feel smart. By putting us in the position of filling in the blanks in the conversation, Newhart gives us the opportunity to feel a little extra satisfaction and to create some of the humor ourselves by crafting our own sense of the rube on the other side of the conversation.

It was the master stroke for a master craftsman. With this brilliant touch, Newhart turned us all into comedians.

Mark Canada, Chancellor and Professor of English, Indiana University Kokomo, Indiana University Kokomo

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Looking for an entertainment experience that transcends the ordinary? Look no further than STM Daily News Blog’s vibrant Entertainment section. Immerse yourself in the captivating world of indie films, streaming and podcasts, movie reviews, music, expos, venues, and theme and amusement parks. Discover hidden cinematic gems, binge-worthy series and addictive podcasts, gain insights into the latest releases with our movie reviews, explore the latest trends in music, dive into the vibrant atmosphere of expos, and embark on thrilling adventures in breathtaking venues and theme parks. Join us at Looking for an entertainment experience that transcends the ordinary? Look no further than STM Daily News Blog’s vibrant Entertainment section. Immerse yourself in the captivating world of indie films, streaming and podcasts, movie reviews, music, expos, venues, and theme and amusement parks. Discover hidden cinematic gems, binge-worthy series and addictive podcasts, gain insights into the latest releases with our movie reviews, explore the latest trends in music, dive into the vibrant atmosphere of expos, and embark on thrilling adventures in breathtaking venues and theme parks. Join us at our Entertainment Section and let your entertainment journey begin! https://stmdailynews.com/category/entertainment/

Discover more from Daily News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Entertainment

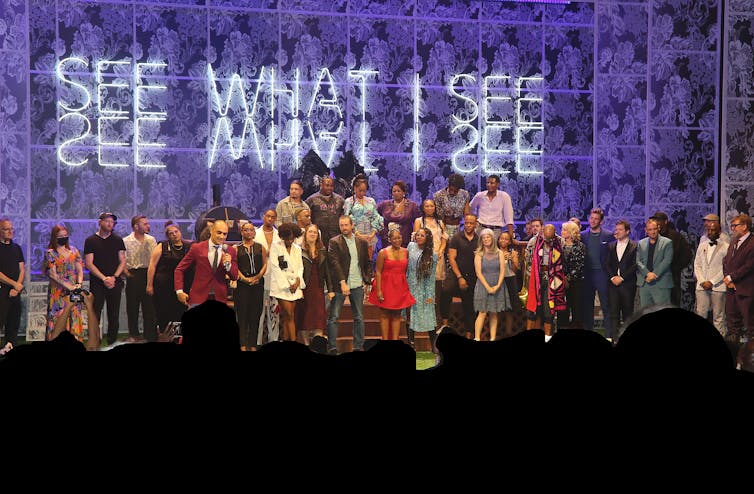

Philly theaters unite to stage 3 plays by Pulitzer-winning playwright James Ijames

James Ijames, 2022 Pulitzer Prize winner for “Fat Ham,” is celebrated with a Citywide Pass in Philadelphia, offering access to three of his plays across different theaters. This initiative fosters collaboration among local theaters and showcases Ijames’ unique ability to create nuanced, character-driven narratives that explore complex queer and Black identities.

Bess Rowen, Villanova University

Most theater subscriptions offer a patron access to a single theater’s season. But Philadelphia’s new Citywide James Ijames Pass provides tickets to three James Ijames – pronounced EYE-ms, rhymes with “chimes” – plays at three theaters in Philadelphia. Subscribers will also get one mustard-colored beanie, one of Ijames’ signature accessories.

The full pass, which costs US$130, includes tickets for the Arden Theatre’s “Good Bones,” which premiered Jan. 22 and runs through March 22, the Wilma Theater’s “The Most Spectacularly Lamentable Trial of Miz Martha Washington,” which runs March 17 to April 5, and the Philadelphia Theatre Company’s “Wilderness Generation,” a world premiere that runs April 10 to May 3. There is also a two-show pass for $90 without “Good Bones.”

I’m a theater theorist, historian and practitioner who has written about Ijames’ work before and after his 2022 Pulitzer Prize. I believe this landmark collaboration between three important Philadelphia theaters is a fitting celebration of a multi-hyphenate theater artist who continues to champion his longtime artistic home.

Actor, playwright, director

Ijames, 46, was born in North Carolina and attended Morehouse College in Atlanta, Georgia. He earned his Master of Fine Arts degree at Temple University and stayed in Philadelphia after graduating.

Notably, this playwright’s MFA is in the study of acting. Ijames is also a talented director, and he performed and directed at multiple theaters around Philadelphia before starting to work as a playwright. He was also a tenured professor of theater at Villanova University, where I had the privilege to work with him and watch his creative process before he moved to New York City in 2025 to run the playwriting concentration at Columbia University.

Ijames was already a local celebrity in Philly before winning the Pulitzer Prize for drama for “Fat Ham,” his Hamlet adaptation centered on a queer Black Hamlet named Juicy and the legacy of his father’s barbecue joint. The New York theater scene took notice of him when the National Black Theatre staged “Kill Move Paradise” in 2017. This haunting piece is set in limbo, where unarmed Black men who have been killed by police examine how they have come to this place and how society continues to enable this pattern.

Other Ijames plays include “White,” a satire of the art world that tells the story of a gay white male artist who hires a Black woman actor to pretend to have done his work to see if that makes a difference in how his art is viewed. “TJ Loves Sally 4Ever” sets Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings’ relationship on a college campus where “TJ” is a dean and Sally is a student. And “Reverie” is a chamber play, which is an intimate meditation with an earnest and somber tone. In it, the father of a recently deceased Black gay man comes to meet the man he believed was his son’s partner.

Most recently, in 2025, Ijames partnered with the Australian pop singer Sia on a musical called “Saturday Church.” It is a story about reconciling queer community and Christian faith, and relying on the support of family, both biological and chosen.

Charting new dramatic territory

Although his theatrical styles and genres vary, at his core, Ijames writes nuanced, character-driven works that revolve around interpersonal relationships. His plays are playgrounds for performers, particularly due to his ability to write complex queer Black characters.

Influential American playwright Suzan-Lori Parks notes in her 1994 essay “Elements of Style” that the conflict between Black people and white people is the default trope of how Black people have been represented onstage – by almost exclusively white playwrights – for most of U.S. theater history. Parks posits that a way to avoid this centering of white conflict in Black lives comes from new dramatic territory that depicts conflicts between Black people and anything else.

Ijames never sets his Black characters in opposition to white society alone. He also refuses to take up the tropes of LGBTQ identity as incompatible with religion, or the idea that characters can be only gay or straight. Instead, Ijames creates narratives with queer religious people and pansexual men whose identities are not sources of conflict.

The citywide pass

The plays in the citywide pass offer an exciting cross section of what makes Ijames’s work so vibrant.

“Good Bones” is the story of a now-affluent Black woman, Aisha, who moves back to her blue-collar hometown. Aisha might be from this working-class neighborhood, but her elaborate renovations and white-collar sensibilities make her return seem more like gentrification than homecoming, at least as far as her local contractor can see.

“Miz Martha” follows the titular Martha Washington through a fever-dream-inspired trial in her final moments, as enslaved people care for her while knowing her death means their freedom.

And “Wilderness Generation” follows five cousins reunited in the U.S. South after many years apart, ready to talk about the secrets from their pasts.

With theater’s ever-changing and unstable financial landscape, I believe the Citywide James Ijames Pass is an exciting new subscriber model. The collaboration highlights Philadelphia’s theatrical talent and banks on local theaters working together to build audiences instead of treating each other as competition – a new development that could change how regional theater scenes operate.

Bess Rowen, Assistant Professor of Theatre, Villanova University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Looking for an entertainment experience that transcends the ordinary? Look no further than STM Daily News Blog’s vibrant Entertainment section. Immerse yourself in the captivating world of indie films, streaming and podcasts, movie reviews, music, expos, venues, and theme and amusement parks. Discover hidden cinematic gems, binge-worthy series and addictive podcasts, gain insights into the latest releases with our movie reviews, explore the latest trends in music, dive into the vibrant atmosphere of expos, and embark on thrilling adventures in breathtaking venues and theme parks. Join us at STM Entertainment and let your entertainment journey begin! https://stmdailynews.com/category/entertainment/

and let your entertainment journey begin!

Discover more from Daily News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Entertainment

Muppets at 50: How Jim Henson’s Felt Icons Became a Billion-Dollar Franchise That Still Prints Money

The Muppets, created by Jim Henson, have thrived for over 50 years, starting with “Sam and Friends” in 1955 and gaining fame through “The Muppet Show” and various films. Despite challenges, including Henson’s passing in 1990 and subsequent ownership changes, The Muppets remain culturally significant, entertaining generations globally.

It’s easy making green: Muppets continue to make a profit 50 years into their run

Jared Bahir Browsh, University of Colorado Boulder

A variety show that’s still revered for its absurdist, slapstick humor debuted 50 years ago. It starred an irreverent band of characters made of foam and fleece.

Long after “The Muppet Show”‘s original 120-episode run ended in 1981, the legend and legacy of Miss Piggy, Fozzie Bear, Gonzo and other creations concocted by puppeteer and TV producer Jim Henson have kept on growing. Thanks to the Muppets’ film franchise and the wonders of YouTube, the wacky gang is still delighting, and expanding, its fan base.

As a scholar of popular culture, I believe that the Muppets’ reign, which began in the 1950s, has helped shape global culture, including educational television. Along the way, the puppets and the people who bring them to life have earned billions in revenue.

Johnny Carson interviews Muppet creator Jim Henson, Kermit and other Muppets on the ‘Tonight Show’ in 1975, ahead of one of an early ‘The Muppet Show’ pilot.

Kermit’s origin story

Muppets, a portmanteau of marionette and puppet, first appeared on TV in the Washington, D.C., region in 1955, when Henson created a short sketch show called “Sam and Friends” with his future wife, Jane Nebel.

Their motley cast of puppets, including a lizardlike character named Kermit, sang parody songs and performed comedy sketches.

Henson’s creations were soon popping up in segments on other TV shows, including “Today” and late-night programs. Rowlf the Dog appeared in Canadian dog food commercials before joining “The Jimmy Dean Show” as the host’s sidekick.

After that show ended, Rowlf and Dean performed on the “Ed Sullivan Show,” where Kermit had occasionally appeared since 1961.

Rowlf the Dog and Jimmy Dean reprise their schtick on the ‘Ed Sullivan Show’ in 1967.

From ‘Sesame Street’ to ‘SNL’

As Rowlf and Kermit made the rounds on variety shows, journalist Joan Ganz Cooney and psychologist Lloyd Morrisett were creating a new educational program. They invited Henson to provide a Muppet ensemble for the show.

Henson waived his performance fee to maintain rights over the characters who became the most famous residents of “Sesame Street.” The likes of Oscar the Grouch, Cookie Monster and Big Bird were joined by Kermit who, by the time the show premiered in 1969, was identified as a frog.

When “Sesame Street” became a hit, Henson worried that his Muppets would be typecast as children’s entertainment. Another groundbreaking show, aimed at young adults, offered him a chance to avoid that.

“Saturday Night Live’s” debut on NBC in 1975 – when the show was called “Saturday Night” – included a segment called “The Land of Gorch,” in which Henson’s grotesque creatures drank, smoked and cracked crass jokes.

“The Land of Gorch” segments ended after “Saturday Night Live’s” first season. ‘Saturday Night Live’s’ first season included ‘Land of Gorch’ sketches that starred creatures Jim Henson made to entertain grown-ups.

Miss Piggy gets her closeup

“The Muppet Show” was years in the making. ABC eventually aired two TV specials in 1974 and 1975 that were meant to be pilots for a U.S.-produced “Muppet Show.”

After no American network picked up his quirky series, Henson partnered with British entertainment entrepreneur Lew Grade to produce a series for ATV, a British network, that featured Kermit and other Muppets. The new ensemble included Fozzie Bear, Animal and Miss Piggy – Muppets originally performed by frequent Henson collaborator Frank Oz.

“The Muppet Show” parodied variety shows on which Henson had appeared. Connections he’d made along the way paid off: Many celebrities he met on those shows’ sets would guest star on “The Muppet Show,” including everyone from Rita Moreno and Lena Horne to Joan Baez and Johnny Cash.

“The Muppet Show,” which was staged and shot at a studio near London, debuted on Sept. 5, 1976, in the U.K, before airing in syndication in the United States on stations like New York’s WCBS.

As the show’s opening and closing theme songs changed over time, they retained a Vaudeville vibe despite the house band’s preference for rock and jazz.

The Muppets hit the big screen

“The Muppet Show” was a hit, amassing a global audience of over 200 million. It won many awards, including a Primetime Emmy for outstanding comedy-variety or music series – for which it beat “Saturday Night Live” – in 1978.

While his TV show was on the air, Henson worked on the franchise’s first film, “The Muppet Movie.” The road film, released in 1979, was another hit: It earned more than US$76 million at the box office.

“The Muppet Movie” garnered two Academy Award nominations for its music, including best song for “Rainbow Connection.” It won a Grammy for best album for children.

The next two films, “The Great Muppet Caper,” which premiered in 1981, and “The Muppets Take Manhattan,” released in 1984, also garnered Oscar nominations for their music.

As ‘The Muppet Movie’ opens, Statler and Waldorf tell a security guard of their heckling plans.

‘Fraggle Rock’ and the Disney deal

The cast of “The Muppet Show” and the three films took a break from Hollywood while Henson focused on “Fraggle Rock,” a TV show for kids that aired from 1983-1987 on HBO.

Like Henson’s other productions, “Fraggle Rock” featured absurdist humor – but its puppets aren’t considered part of the standard Muppets gang. This co-production between Henson, Canadian Broadcast Corporation and British producers was aimed at international markets.

The quickly conglomerating media industry led Henson to consider corporate partnerships to assist with his goal of further expanding the Muppet media universe.

In August 1989, he negotiated a deal with Michael Eisner of Disney who announced at Disney-MGM Studios an agreement in principle to acquire The Muppets, with Henson maintaining ownership of the “Sesame Street” characters.

The announcement also included plans to open Muppet-themed attractions at Disney parks.

But less than a year later, on May 16, 1990, Henson died from a rare and serious bacterial infection. He was 53.

At the end of ‘Fraggle Rock’s’ run, its characters look for new gigs.

Of Muppets and mergers

Henson’s death led to the Disney deal’s collapse. But the company did license The Muppets to Disney, which co-produced “The Muppet Christmas Carol” in 1992 and “Muppet Treasure Island” in 1996 with Jim Henson Productions, which was then run by Jim’s son, Brian Henson.

In 2000, the Henson family sold the Muppet properties to German media company EM.TV & Merchandising AG for $680 million. That company ran into financial trouble soon after, then sold the Sesame Street characters to Sesame Workshop for $180 million in late 2000. The Jim Henson Company bought back the remaining Muppet properties for $84 million in 2003.

In 2004, Disney finally acquired The Muppets and most of the media library associated with the characters.

Disney continued to produce Muppet content, including “The Muppet’s Wizard of Oz” in 2005. Its biggest success came with the 2011 film “The Muppets,” which earned over $165 million at the box office and won the Oscar for best original song “Man or Muppet.”

“Muppets Most Wanted,” released in 2014, earned another $80 million worldwide, bringing total global box office receipts to over $458 million across eight theatrical Muppets movies.

The ‘Muppet Show’ goes on

The Muppets continue to expand their fandom across generations and genres by performing at live concerts and appearing in several series and films.

Through these many hits and occasional bombs, and the Jim Henson Company’s personnel changes, the Muppets have adapted to changes in technology and tastes, making it possible for them to remain relevant to new generations.

That cast of characters made of felt and foam continue to entertain fans of all ages. Although many people remain nostalgic over “The Muppet Show,” two prior efforts to reboot the show proved short-lived.

But when Disney airs its “The Muppet Show” anniversary special on Feb. 4, 2026, maybe more people will get hooked as Disney looks to reboot the series

‘The Muppet Show’ will be back – for at least one episode – on Feb. 4, 2026.

Jared Bahir Browsh, Assistant Teaching Professor of Critical Sports Studies, University of Colorado Boulder

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Discover more from Daily News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.