The Bridge

Researchers Find that to Achieve Long-term Sustainability, Urban Systems Must Tackle Social Justice and Equity

Inclusivity and understanding past policies and their effects on underserved and marginalized communities must be part of urban planning, design, and public policy efforts for cities.

Joe F. Bozeman III, the lead author and an assistant professor in Georgia Tech’s School of Civil and Environmental Engineering. He is also the director of Tech’s Social Equity & Environmental Engineering Lab.

« Researchers Find that to Achieve Long-term Sustainability, Urban Systems Must Tackle Social Justice and Equity

Newswise — Inclusivity and understanding past policies and their effects on underserved and marginalized communities must be part of urban planning, design, and public policy efforts for cities.

An international coalition of researchers — led by Georgia Tech — have determined that advancements and innovations in urban research and design must incorporate serious analysis and collaborations with scientists, public policy experts, local leaders, and citizens. To address environmental issues and infrastructure challenges cities face, the coalition identified three core focus areas with research priorities for long-term urban sustainability and viability. Those focus areas should be components of any urban planning, design, and sustainability initiative.

The researchers found that the core focus areas included social justice and equity, circularity, and a concept called “digital twins.” The team — which consists of 13 co-authors and scholars based in the U.S., Asia, and Europe — also provided guidance and future research directions for how to address these focus areas. They detailed their findings in the Journal of Industrial Ecology, published in January 2023.

“Climate change has certainly increased the amount and intensity of extreme weather events and because of that, it makes our decision making today critical to the manner in which our economy and our day to day lives can operate,” said Joe F. Bozeman III, the lead author and an assistant professor in Georgia Tech’s School of Civil and Environmental Engineering. He is also the director of Tech’s Social Equity & Environmental Engineering Lab. “Our quality of life can be negatively affected if we don’t make good decisions today.”

Three core areas of focus to achieve urban sustainability

The researchers’ first core focus area, justice and equity, addresses innovations and trends that disproportionately benefit middle and high-income communities. Trends like IoT, “smart cities,” and the urban “green movement” are part of a broader push by cities to become more sustainable and resilient. But communities of color and low-income neighborhoods — the same areas often home to environmental contaminations, infrastructure challenges, and other hazards — have often been overlooked.

The researchers’ findings showed a consistent trend with marginalized communities across several countries, including Canada, the Netherlands, India, and South Africa. They call for mandatory equity analyses which incorporate the experiences and perspectives of these marginalized communities, and, more importantly, ensure members of those communities are actively engaged in decision-making processes.

“Planning, professional, and community stakeholders,” the researchers write in the paper, “should recognize that working together gets cities closer to harmonizing the technological and social dimensions of sustainability.”

The second focus area, circularity, addresses resource consumption of staple commodities including food, water, and energy; the waste and emissions they generate; and the opportunities to increase conservation of those resources by boosting efficiencies.

“What we mean by circularity is basic reuse, remanufacturing, and recycling efforts across the entire urban system — which not only includes cities and under resourced areas within those cities — but also rural communities that supply and take resources from those city hubs,” Bozeman said. The idea is aligned with the circular economy concept which addresses the need to move away from the resource-wasteful and unsustainable cycle of taking, making, and throwing away.

Instead, the researchers argue, cities should look for ways to improve efficiency and maximize local resource use. That has potential benefits not only for urban areas, but rural communities, too. One example, Bozeman said, is the Lifecycle Building Center in Atlanta. It takes old building supplies and sells them locally for reuse.

“By doing that, they’re at the beginning stages of creating an economic system, a regional engine where we share resources between cities and rural areas,” he said. “We can start creating an economic framework, not only where both sides can make money and get what they need, but something that can actually turn into a sustainable economic engine without having to rely on another state or another country’s import or export economic pressures.”

To strengthen circularity and make it more robust, the researchers call for more expansive metrics beyond measuring recycling rates and zero waste efforts, to include other parts of the supply chain that may yield new ideas and solutions.

The third focus area, digital twins, addresses the development of automated technologies in smart buildings and infrastructure, such as traffic lights to respond to weather and other environmental factors.

“Let’s say there’s a heavy rain event and that the rainwater is being stored into retainment,” said Bozeman. “An automated system can open another valve where we can store that water into a secondary support system, so there’s less flooding, and that can happen automatically, if we utilize the concept of digital twins.”

Creating a new urban planning model

The research came about as part of the mission of the Sustainable Urban Systems Section of the International Society for Industrial Ecology, which aims to be a conduit for scientists, engineers, policymakers, and others who want to marry environmental concerns and economic activity. Bozeman is a board member of the Sustainable Urban Systems Section.

“In that role, part of we do is set a vision and foundation for how other researchers should operate within the city and urban system space,” he said.

For urban sustainability, engineers and policy makers must come to the table and make collective decisions around social justice and equity, circularity, and the digital twins concepts.

“I think we’re at a really critical decision point when it comes to engineers and others being able to do work that is forward looking and human sensitive,” said Bozeman. “Good decision making involves addressing social justice and equity and understanding its root causes, which will enable cities to create solutions that integrate cultural dynamics.”

CITATION: Joe F. Bozeman III, Shauhrat S. Chopra, Philip James, Sajjad Muhammad, Hua Cai, Kangkang Tong, Maya Carrasquillo, Harold Rickenbacker, Destenie Nock, Weslynne Ashton, Oliver Heidrich, Sybil Derrible, Melissa Bilec. “Three research priorities for just and sustainable urban systems: Now is the time to refocus.” (Journal of Industrial Ecology, January 2023)

About Georgia Institute of Technology

The Georgia Institute of Technology, or Georgia Tech, is a public research university developing leaders who advance technology and improve the human condition. The Institute offers business, computing, design, engineering, liberal arts, and sciences degrees. Its nearly 44,000 students representing 50 states and 149 countries, study at the main campus in Atlanta, at campuses in France and China, and through distance and online learning. As a leading technological university, Georgia Tech is an engine of economic development for Georgia, the Southeast, and the nation, conducting more than $1 billion in research annually for government, industry, and society.

Discover more from Daily News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Bridge

Scrappy, campy and unabashedly queer, public access TV series of the 1980s and 1990s offered a rare glimpse into LGBTQ+ life

Last Updated on March 10, 2026 by Daily News Staff

“Hello to all you lovely lesbians out there! My name is Debbie, and I’m here to show you a few things about taking care of your vaginal health.”

So opens the first “Lesbian Health” segment on “Dyke TV,” a lesbian feminist television series that aired on New York’s public access stations from 1993 to 2006.

The half-hour program focused on lesbian activism, community issues, art and film, news, health, sports and culture. Created by three artist-activists – Cuban playwright Ana Simo, theater director and producer Linda Chapman and independent filmmaker Mary Patierno – “Dyke TV” was one of the first TV shows made by and for LGBTQ women.

While many people might think LGBTQ+ representation on TV began in the 1990s on shows like “Ellen” and “Will & Grace,” LGBTQ+ people had already been producing their own television programming on local stations in the U.S. and Canada for decades.

In fact my research has identified hundreds of LGBTQ+ public access series produced across the country.

In a media environment historically hostile to LGBTQ+ people and issues, LGBTQ+ people created their own local programming to shine a spotlight on their lives, communities and concerns.

Experimentation and advocacy

On this particular health segment on “Dyke TV,” a woman proceeds to give herself a cervical exam in front of the camera using a mirror, a flashlight and a speculum.

Close-up shots of this woman’s genitalia show her vulva, vagina and cervix as she narrates the exam in a matter-of-fact tone, explaining how viewers can use these tools on their own to check for vaginal abnormalities. Recalling the ethos of the women’s health movement of the 1970s, “Dyke TV” instructs audiences to empower themselves in a world where women’s health care is marginalized.

Because public access TV in New York was relatively unregulated, the show’s hosts could openly discuss sexual health and air segments that would otherwise be censored on broadcast networks.

Like today’s LGBTQ content creators, many of the producers of LGBTQ+ public access series experimented with genre, form and content in entertaining and imaginative ways.

LGBTQ+ actors, entertainers, activists and artists – who often experienced discrimination and tokenism on mainstream media – appeared on these series to publicize and discuss their work. Iconic drag queen RuPaul got his start performing on public access in Atlanta, where “The American Music Show” gave him a platform to promote his burgeoning drag persona in the mid-1980s. https://www.youtube.com/embed/hab5HrnfEZk?wmode=transparent&start=0 RuPaul appears on a 1985 episode of ‘The American Music Show.’

The producers often saw their series as a blend of entertainment, art and media activism.

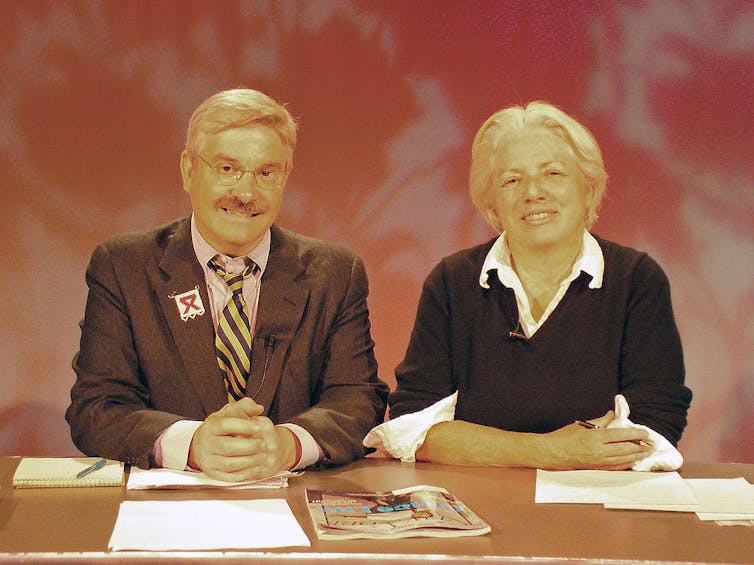

Shows like “The Gay Dating Game” and “Be My Guest” were tongue-in-cheek satires of 1950s game shows. News programs such as “Gay USA,” which broadcast its first episode in 1985, reported on local and national LGBTQ news and health issues.

Variety shows like “The Emerald City” in the 1970s, “Gay Morning America” in the 1980s, and “Candied Camera” in the 1990s combined interviews, musical performances, comedy skits and news programming. Scripted soap operas, like “Secret Passions,” starred amateur gay actors. And on-the-street interview programs like “The Glennda and Brenda Show” used drag and street theater to spark discussions about LGBTQ issues.

Other programs featured racier content.

In the 1980s and ‘90s, “Men & Films,” “The Closet Case Show” and “Robin Byrd’s Men for Men” incorporated interviews with porn stars, clips from porn videos and footage of sex at nightclubs and parties.

Skirting the censors

The regulation of sex on cable television has long been a political and cultural flashpoint.

But regulatory loopholes inadvertently allowed sexual content on public access. This allowed hosts and guests to talk openly about gay sex and safer sex practices on these shows – and even demonstrate them on camera.

The impetus for public access television was similar to the ethos of public broadcasting, which sought to create noncommercial and educational television programming in the service of the public interest.

In 1972, the Federal Communications Commission issued an order requiring cable television systems in the country’s top 100 markets to offer access channels for public use. The FCC mandated that cable companies make airtime, equipment and studio space to individuals and community groups to use for their own programming on a first-come, first-serve basis.

The FCC’s regulatory authority does not extend to editorial control over public access content. For this reason, repeated attempts to block, regulate and censor programming throughout the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s were challenged by cable access producers and civil liberties organizations.

The Supreme Court has continually struck down laws that attempt to censor cable access programming on First Amendment grounds. A cable operator can refuse to air a program that contains “obscenity,” but what counts as obscenity is up for interpretation.

Over the years, producers of LGBTQ-themed shows have fiercely defended their programming from calls for censorship, and the law has consistently been on their side.

Airing the AIDS crisis

As the AIDS crisis began to devastate LGBTQ+ communities in the 1980s, public access television grew increasingly important.

Many of the aforementioned series devoted multiple segments and episodes to discussing the devastating impact of HIV/AIDS on their personal lives, relationships and communities. Series like “Living with AIDS”, “HoMoVISIONES” and “ACT UP Live!” were specifically designed to educate and galvanize viewers around HIV/AIDS activism. With HIV/AIDS receiving minimal coverage on mainstream media outlets – and a lack of political action by local, state and national officials – these programs were some of the few places where LGBTQ+ people could learn the latest information about the epidemic and efforts to combat it.

The long-running program “Gay USA” is one of the few remaining LGBTQ+ public access series; new episodes air locally in New York and nationally via Free Speech TV each week. While public access stations still exist in most cities around the country, production has waned since the advent of cheaper digital media technologies and streaming video services in the mid-2000s.

And yet during this media era – let’s call it “peak public access TV” – these scrappy, experimental, sexual, campy and powerful series offered remarkable glimpses into LGBTQ+ culture, history and activism.

Lauren Herold, Visiting Assistant Professor of Gender & Sexuality Studies, Kenyon College

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The Bridge is a section of the STM Daily News Blog meant for diversity, offering real news stories about bona fide community efforts to perpetuate a greater good. The purpose of The Bridge is to connect the divides that separate us, fostering understanding and empathy among different groups. By highlighting positive initiatives and inspirational actions, The Bridge aims to create a sense of unity and shared purpose. This section brings to light stories of individuals and organizations working tirelessly to promote inclusivity, equality, and mutual respect. Through these narratives, readers are encouraged to appreciate the richness of diverse perspectives and to participate actively in building stronger, more cohesive communities.

https://stmdailynews.com/category/the-bridge

Discover more from Daily News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Urbanism

Los Angeles is in a 4-year sprint to deliver a car-free 2028 Olympics

Last Updated on March 8, 2026 by Daily News Staff

Jay L. Zagorsky, Boston University

With the Olympic torch extinguished in Paris, all eyes are turning to Los Angeles for the 2028 Olympics.

The host city has promised that the next Summer Games will be “car-free.”

For people who know Los Angeles, this seems overly optimistic. The car remains king in LA, despite growing public transit options.

When LA hosted the Games in 1932, it had an extensive public transportation system, with buses and an extensive network of electric streetcars. Today, the trolleys are long gone; riders say city buses don’t come on schedule, and bus stops are dirty. What happened?

This question fascinates me because I am a business professor who studies why society abandons and then sometimes returns to certain technologies, such as vinyl records, landline phones and metal coins. The demise of electric streetcars in Los Angeles and attempts to bring them back today vividly demonstrate the costs and challenges of such revivals. https://www.youtube.com/embed/9X78ZqGyc5o?wmode=transparent&start=0 The 2028 Olympic Games will be held in existing sports venues around Los Angeles and are expected to host 15,000 athletes and over 1 million spectators.

Riding the Red and Yellow Cars

Transportation is a critical priority in any city, but especially so in Los Angeles, which has been a sprawling metropolis from the start.

In the early 1900s, railroad magnate Henry Huntington, who owned vast tracts of land around LA, started subdividing his holdings into small plots and building homes. In order to attract buyers, he also built a trolley system that whisked residents from outlying areas to jobs and shopping downtown.

By the 1930s, Los Angeles had a vibrant public transportation network, with over 1,000 miles of electric streetcar routes, operated by two companies: Pacific Electric Railway, with its “Red Cars,” and Los Angeles Railway, with its “Yellow Cars.”

The system wasn’t perfect by any means. Many people felt that streetcars were inconvenient and also unhealthy when they were jammed with riders. Moreover, streetcars were slow because they had to share the road with automobiles. As auto usage climbed and roads became congested, travel times increased.

Nonetheless, many Angelenos rode the streetcars – especially during World War II, when gasoline was rationed and automobile plants shifted to producing military vehicles. https://www.youtube.com/embed/AwKv3_WwD4o?wmode=transparent&start=0 In 1910, Los Angeles had a widely used local rail network, with over 1,200 miles (1,930 kilometers) of track. What happened?

Demise of public transit

The end of the war marked the end of the line for streetcars. The war effort had transformed oil, tire and car companies into behemoths, and these industries needed new buyers for goods from the massive factories they had built for military production. Civilians and returning soldiers were tired of rationing and war privations, and they wanted to spend money on goods such as cars.

After years of heavy usage during the war, Los Angeles’ streetcar system needed an expensive capital upgrade. But in the mid-1940s, most of the system was sold to a company called National City Lines, which was partly owned by the carmaker General Motors, the oil companies Standard Oil of California and Phillips Petroleum, and the Firestone tire company.

These powerful forces had no incentive to maintain or improve the old electric streetcar system. National City ripped up tracks and replaced the streetcars with buses that were built by General Motors, used Firestone tires and ran on gasoline.

There is a long-running academic debate over whether self-serving corporate interests purposely killed LA’s streetcar system. Some researchers argue that the system would have died on its own, like many other streetcar networks around the world.

The controversy even spilled over into pop culture in the 1988 movie “Who Framed Roger Rabbit,” which came down firmly on the conspiracy side.

What’s undisputed is that, starting in the mid-1940s, powerful social forces transformed Los Angeles so that commuters had only two choices: drive or take a public bus. As a result, LA became so choked with traffic that it often took hours to cross the city.

In 1990, the Los Angeles Times reported that people were putting refrigerators, desks and televisions in their cars to cope with getting stuck in horrendous traffic. A swath of movies, from “Falling Down” to “Clueless” to “La La Land,” have featured the next-level challenge of driving in LA.

Traffic was also a concern when LA hosted the 1984 Summer Games, but the Games went off smoothly. Organizers convinced over 1 million people to ride buses, and they got many trucks to drive during off-peak hours. The 2028 games, however, will have roughly 50% more athletes competing, which means thousands more coaches, family, friends and spectators. So simply dusting off plans from 40 years ago won’t work.

Olympic transportation plans

Today, Los Angeles is slowly rebuilding a more robust public transportation system. In addition to buses, it now has four light-rail lines – the new name for electric streetcars – and two subways. Many follow the same routes that electric trolleys once traveled. Rebuilding this network is costing the public billions, since the old system was completely dismantled.

Three key improvements are planned for the Olympics. First, LA’s airport terminals will be connected to the rail system. Second, the Los Angeles organizing committee is planning heavily on using buses to move people. It will do this by reassigning some lanes away from cars and making them available for 3,000 more buses, which will be borrowed from other locales.

Finally, there are plans to permanently increase bicycle lanes around the city. However, one major initiative, a bike path along the Los Angeles River, is still under an environmental review that may not be completed by 2028.

Car-free for 17 days

I expect that organizers will pull off a car-free Olympics, simply by making driving and parking conditions so awful during the Games that people are forced to take public transportation to sports venues around the city. After the Games end, however, most of LA is likely to quickly revert to its car-centric ways.

As Casey Wasserman, chair of the LA 2028 organizing committee, recently put it: “The unique thing about Olympic Games is for 17 days you can fix a lot of problems when you can set the rules – for traffic, for fans, for commerce – than you do on a normal day in Los Angeles.”

This article has been updated to indicate that Los Angeles has four light-rail lines.

Jay L. Zagorsky, Associate Professor of Markets, Public Policy and Law, Boston University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Dive into “The Knowledge,” where curiosity meets clarity. This playlist, in collaboration with STMDailyNews.com, is designed for viewers who value historical accuracy and insightful learning. Our short videos, ranging from 30 seconds to a minute and a half, make complex subjects easy to grasp in no time. Covering everything from historical events to contemporary processes and entertainment, “The Knowledge” bridges the past with the present. In a world where information is abundant yet often misused, our series aims to guide you through the noise, preserving vital knowledge and truths that shape our lives today. Perfect for curious minds eager to discover the ‘why’ and ‘how’ of everything around us. Subscribe and join in as we explore the facts that matter. https://stmdailynews.com/the-knowledge/

Discover more from Daily News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Bridge

Celebrating International Women’s Day!

International Women’s Day is celebrated globally on March 8th to honor women’s achievements and promote gender equality, originating from a 1908 march in New York for better rights.

Last Updated on March 7, 2026 by Daily News Staff

International Women’s Day is a global celebration that honors the achievements of women and highlights the progress still to be made in the fight for gender equality. On this day, people around the world come together to recognize the amazing contributions of women everywhere and to rally for greater gender equity in all areas of life.

The origins of International Women’s Day can be traced back to 1908, when 15,000 women marched through the streets of New York City to demand better working conditions and the right to vote. Since then, the celebration has grown to be an international event, with more than 100 countries recognizing the day. The United Nations even declared March 8th as International Women’s Day in 1975, to honor the struggles of women around the world.

This year’s International Women’s Day theme is #ChooseToChallenge, meaning that everyone is encouraged to call out gender bias and inequality when they see it. We’re also encouraged to celebrate women’s achievements, support each other, and take action for equality.

It’s important to recognize the progress we’ve made in terms of gender equality, but we still have a long way to go. International Women’s Day serves as a reminder that we must continue to fight for gender equality in all areas of life. Let’s use this day to honor the contributions of women around the world, and to continue the fight for a more equitable world.

https://www.internationalwomensday.com/

https://stmdailynews.com/category/science/

Discover more from Daily News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.