The Bridge

There’s a strange history of white journalists trying to better understand the Black experience by ‘becoming’ Black

The article critiques white journalists who try to experience Black life by pretending to be Black, arguing these efforts are superficial, reinforce stereotypes, and trivialize systemic racism and the Black experience.

Last Updated on September 21, 2024 by Daily News Staff

Alisha Gaines, Florida State University

A peculiar desire seems to still haunt some white people: “I wish I knew what it was like to be Black.”

This wish is different from wanting to cosplay the coolness of Blackness – mimicking style, aping music and parroting vernacular.

This is a presumptive, racially imaginative desire, one that covets not just the rhythm of Black life, but also its blues.

While he doesn’t want to admit it, Canadian-American journalist Sam Forster is one of those white people.

Three years after hearing George Floyd cry “Mama” so desperately that it brought a country out of quarantine, Forster donned a synthetic Afro wig and brown contacts, tinted his eyebrows and smeared his face with CVS-bought Maybelline liquid foundation in the shade of “Mocha.” Though Forster did not achieve a “movie-grade” transformation, he became, in his words, “Believably Black.”

He went on to attempt a racial experiment no one asked for, one that he wrote about in his recently published memoir, “Seven Shoulders: Taxonomizing Racism in Modern America.”

For two weeks in September 2023, Forster pretended to hitchhike on the shoulder of a highway in seven different U.S. cities: Nashville, Tennessee; Atlanta; Birmingham, Alabama; Los Angeles; Las Vegas; Chicago and Detroit. On the first day in town, he would stand on the side of the road as his white self, seeing who, if anyone, would stop and offer him a ride. On the second day, he stuck out his thumb on the same shoulder, but this time in what I’d describe as “mochaface.”

Since September is hot, he set a two-hour limit for his experiments. During his seven white days, he was offered, but did not take, seven rides. On seven subsequent Black days, he was offered, but did not take, one ride. He speculated that day was a fluke.

Forster is not the first white person to center themselves in the discussion of American racism by pretending to be Black.

His wish mirrors that of the white people featured in my 2017 book, “Black for a Day: White Fantasies of Race and Empathy.” The book tells the history of what I call “empathetic racial impersonation,” in which white people indulge in their fantasies of being Black under the guise of empathizing with the Black experience.

To me, these endeavors are futile. They end up reinforcing stereotypes and failing to address systemic racism, while conferring a false sense of racial authority.

Going undercover in the South

The genealogy begins in the late 1940s with Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Ray Sprigle.

Sprigle, a white reporter at the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, decided he wanted to experience postwar racism by “becoming” a Black man. After unsuccessfully trying to darken his skin beyond a tan, Sprigle shaved his head, put on giant glasses and traded his signature, 10-gallon hat for an unassuming cap. For four weeks beginning in May 1948, Sprigle navigated the Jim Crow South as a light-skinned Black man named James Rayel Crawford.

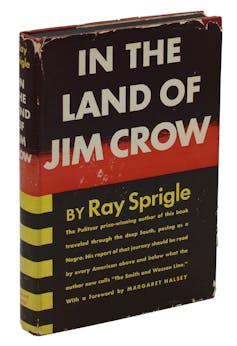

Sprigle documented dilapidated sharecropper’s cabins, segregated schools and women widowed by lynching. What he witnessed – but did not experience – informed his 21-part series of front page articles for the Post-Gazette. He followed up the series by publishing a widely panned 1949 memoir, “In the Land of Jim Crow.”

Sprigle never won that second Pulitzer.

Cosplaying as Black

Sprigle’s more famous successor, John Howard Griffin, published his memoir, “Black Like Me,” in 1961.

Like Sprigle, Griffin explored the South as a temporary Black man, darkening his skin with pills intended to treat vitiligo, a skin disease that causes splotchy losses of pigmentation. He also used stains to even his skin tone and spent time under a tanning lamp.

During his weeks as “Joseph Franklin,” Griffin encountered racism on a number of occasions: White thugs chased him, bus drivers refused to let him disembark to pee, store managers denied him work, closeted, gay white men aggressively hit on him, and otherwise nice-seeming white people grilled him with what Griffin called the “hate stare.” Once Griffin resumed being white and news broke about his racial experiment, his white neighbors from his hometown in Mansfield, Texas, hanged him in effigy.

For his work, Griffin was lauded as an icon in empathy. Since, unlike Sprigle, he experienced racist incidents himself, Griffin showed skeptical white readers what they refused to believe: Racism was real. The book became a bestseller and a movie, and is still included in school curricula – at the expense, I might add, of African-American literature.

Griffin’s importance to this genealogy extends beyond middle-schoolers reading “Black Like Me,” to his successor and mentee, Grace Halsell.

Halsell, a freelance journalist and former staff writer for Lyndon B. Johnson’s administration, decided to “become” a Black woman – first in Harlem in New York City, and then in Mississippi.

Without consulting any Black woman before baking herself caramel in tropical suns and using Griffin’s doctors to administer vitiligo-corrective medication, Halsell initially planned to “be” Black for a year. But after alleging someone attempted to sexually assault her while she was working as a Black domestic worker, Halsell ended her stint as a Black woman early.

Although her experiment only lasted six months, she still claimed to be someone who could authentically represent her “darker sisters” in her 1969 memoir, “Soul Sister.”

Turn-of-the-century ‘race switching’

Forster writes that his 2024 memoir is the “fourth act” – after Sprigle, Griffin and Halsell – of what he calls “journalistic blackface.”

However, he is not, as he claims, “the first person to earnestly cross the color barrier in over half a century.”

In a 174-page book self-described as “gonzo” with only 17 citations, Forster failed to finish his homework.

In 1994, Joshua Solomon, a white college student, medically dyed his skin to “become” a Black man after reading “Black Like Me.” His originally planned, monthlong experiment in Georgia only lasted a few days. But he nonetheless detailed his experiences in an article for The Washington Post and netted an appearance on “The Oprah Winfrey Show.”

Then, in 2006, FX released, “Black. White.,” a six-part reality television series advertised as the “ultimate racial experiment.”

Two families – one white, the other Black – “switched” their races to perform versions of each-otherness while living together in Los Angeles. While the makeup team won a Primetime Emmy Award, the families said goodbye seething with resentment instead of understanding.

A masterclass of white arrogance

Believing it would distract from the findings of his experiment, Forster refuses to show readers his mochaface.

Even after confronting evidence forcing him to question his project’s appropriateness, like the multiple articles condemning “wearing makeup to imitate the appearance of a Black person,” he insists his insights into American racism justify his methods and are different from the harmful legacies of blackface. As he stands on the side of the road, sun and sweat compromising whatever care he took to paint his face, Forster concludes that racism can be divided into two broad taxonomies: institutional and interpersonal.

The former, he believes, “is effectively dead,” and the latter is most often experienced as “shoulder,” like the subtle refusal to pick up a mocha-faced hitchhiker.

Forster’s Amazon book description touts “Seven Shoulders” as “the most important book on American race relations that has ever been written.”

Indeed, it is a masterclass – but one on the arrogance of white assumptions about Blackness.

To believe that the richness of Black identity can be understood through a temporary costume trivializes the lifelong trauma of racism. It turns the complexity of Black life into a stunt.

Whether it’s Forster’s premise that Black people are ill-equipped to testify about their own experiences, his sketchy citations, the hubris of his caricature or the venom with which he speaks about the Black Lives Matter movement, Forster offers an important reminder that liberation can’t be bought at the drugstore.

Alisha Gaines, Associate Professor of English, Florida State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The Bridge is a section of the STM Daily News Blog meant for diversity, offering real news stories about bona fide community efforts to perpetuate a greater good. The purpose of The Bridge is to connect the divides that separate us, fostering understanding and empathy among different groups. By highlighting positive initiatives and inspirational actions, The Bridge aims to create a sense of unity and shared purpose. This section brings to light stories of individuals and organizations working tirelessly to promote inclusivity, equality, and mutual respect. Through these narratives, readers are encouraged to appreciate the richness of diverse perspectives and to participate actively in building stronger, more cohesive communities.

https://stmdailynews.com/category/the-bridge

Discover more from Daily News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Community

Chick-fil-A Awards $6 Million in True Inspiration Awards Grants to 56 Nonprofits

Chick-fil-A is awarding $6 million in 2026 True Inspiration Awards grants to 56 nonprofits, including a $350,000 honoree grant to San Antonio’s Faith Kitchen.

Chick-fil-A, Inc. is awarding $6 million in grants to 56 nonprofit organizations as part of its 2026 True Inspiration Awards® program, spotlighting groups the company says are making measurable, community-level impact.

The Feb. 10 announcement also marks a global milestone for the brand: Chick-fil-A is expanding the program’s footprint to include its first-ever Singapore-based grant recipient.

The big picture: a decade of community grants

Chick-fil-A launched the True Inspiration Awards in 2015 to honor the legacy of its founder, S. Truett Cathy. Since then, the company says it has awarded more than 400 grants totaling nearly $40 million to nonprofits across the U.S., Canada, Puerto Rico, the U.K. and now Singapore.

“Serving is at the heart of what we do, and the True Inspiration Awards reflect our belief that strong communities are built through consistent, caring action,” said Andrew T. Cathy, CEO of Chick-fil-A, Inc., in the release.

Faith Kitchen named 2026 S. Truett Cathy Honoree

This year’s S. Truett Cathy Honoree — the program’s top recognition and largest grant — went to Faith Kitchen, a San Antonio-based nonprofit focused on serving people experiencing homelessness.

Faith Kitchen received a $350,000 grant, which Chick-fil-A says will help:

- Support continued meal service

- Expand job training programs

- Increase operational capacity as demand rises

According to the release, Faith Kitchen serves more than 5,000 individuals each year and has operated with a mission of feeding those experiencing homelessness for 45 years, providing hot, nutritious meals three times per day.

Shared Table partnership: surplus food turned into meals

Chick-fil-A also highlighted its ongoing relationship with Faith Kitchen through the Chick-fil-A Shared Table®program, which donates surplus food from restaurants.

Since 2017, Chick-fil-A restaurants in San Antonio have partnered with Faith Kitchen to help create more than 200,000 meals, according to the company. The release also notes restaurants donate 500 boxed meals monthly to support Faith Kitchen clients.

Local Owner-Operator Greg Patterson said he nominated Faith Kitchen for the grant, citing the organization’s focus on dignity and dependable support.

Global expansion: first Singapore recipient

A notable headline for 2026 is the program’s first Singapore recipient: Fei Yue Community Services, which received $170,000 SGD.

Chick-fil-A says the organization supports socially withdrawn youth by connecting them with mental health resources and supportive relationships.

More nonprofits recognized across the U.S.

While Chick-fil-A’s full list of 2026 recipients is available through the company’s program page, the release highlights several additional grant recipients, including:

- Living and Learning Enrichment Center (Detroit, Michigan): $125,000 to support teens and young adults with disabilities transitioning to adulthood

- For Oak Cliff (North Texas): $200,000 to strengthen culturally responsive programs and expand access to education, workforce development, and community resources

- San Diego Rescue Mission (San Diego, California): $125,000 to provide trauma-informed support for individuals and families facing homelessness

- Capital City Youth Services (Tallahassee, Florida): selected to help expand emergency shelter and mental health support for at-risk youth

Chick-fil-A One members helped vote — nearly 700,000 ballots

Chick-fil-A says Chick-fil-A One® Members voted for Operator-nominated nonprofits in the Chick-fil-A App, and that voting plays a role in the final scoring. This year, the company reported a record nearly 700,000 votes cast.

2027 application window is open

Nonprofits interested in the next cycle can take note: Chick-fil-A says the 2027 True Inspiration Awards application period opens today and closes May 1.

For more information and the interactive release, visit: https://www.multivu.com/chick-fil-a/9376351-en-chick-fil-a-true-inspiration-awards-grants

Our Lifestyle section on STM Daily News is a hub of inspiration and practical information, offering a range of articles that touch on various aspects of daily life. From tips on family finances to guides for maintaining health and wellness, we strive to empower our readers with knowledge and resources to enhance their lifestyles. Whether you’re seeking outdoor activity ideas, fashion trends, or travel recommendations, our lifestyle section has got you covered. Visit us today at https://stmdailynews.com/category/lifestyle/ and embark on a journey of discovery and self-improvement.

Discover more from Daily News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Urbanism

The Building That Proved Los Angeles Could Go Vertical

Los Angeles once banned skyscrapers, yet City Hall broke the height limit and proved high-rise buildings could be engineered safely in an earthquake zone.

Last Updated on February 19, 2026 by Daily News Staff

How City Hall Quietly Undermined LA’s Own Height Limits

The Knowledge Series | STM Daily News

For more than half a century, Los Angeles enforced one of the strictest building height limits in the United States. Beginning in 1905, most buildings were capped at 150 feet, shaping a city that grew outward rather than upward.

The goal was clear: avoid the congestion, shadows, and fire dangers associated with dense Eastern cities. Los Angeles sold itself as open, sunlit, and horizontal — a place where growth spread across land, not into the sky.

And yet, in 1928, Los Angeles City Hall rose to 454 feet, towering over the city like a contradiction in concrete.

It wasn’t built to spark a commercial skyscraper boom.

But it ended up proving that Los Angeles could safely build one.

A Rule Designed to Prevent a Manhattan-Style City

The original height restriction was rooted in early 20th-century fears:

- Limited firefighting capabilities

- Concerns over blocked sunlight and airflow

- Anxiety about congestion and overcrowding

- A strong desire not to resemble New York or Chicago

Los Angeles wanted prosperity — just not vertical density.

The height cap reinforced a development model where:

- Office districts stayed low-rise

- Growth moved outward

- Automobiles became essential

- Downtown never consolidated into a dense core

This philosophy held firm even as other American cities raced upward.

Why City Hall Was Never Meant to Change the Rules

City Hall was intentionally exempt from the height limit because the law applied primarily to private commercial buildings, not civic monuments.

But city leaders were explicit about one thing:

City Hall was not a precedent.

It was designed to:

- Serve as a symbolic seat of government

- Stand alone as a civic landmark

- Represent stability, authority, and modern governance

- Avoid competing with private office buildings

In effect, Los Angeles wanted a skyline icon — without a skyline.

Innovation Hidden in Plain Sight

What made City Hall truly significant wasn’t just its height — it was how it was built.

At a time when seismic science was still developing, City Hall incorporated advanced structural ideas for its era:

- A steel-frame skeleton designed for flexibility

- Reinforced concrete shear walls for lateral strength

- A tapered tower to reduce wind and seismic stress

- Thick structural cores that distributed force instead of resisting it rigidly

These choices weren’t about aesthetics — they were about survival.

The Earthquake That Changed the Conversation

In 1933, the Long Beach earthquake struck Southern California, causing widespread damage and reshaping building codes statewide.

Los Angeles City Hall survived with minimal structural damage.

This moment quietly reshaped the debate:

- A tall building had endured a major earthquake

- Structural engineering had proven effective

- Height alone was no longer the enemy — poor design was

City Hall didn’t just survive — it validated a new approach to vertical construction in seismic regions.

Proof Without Permission

Despite this success, Los Angeles did not rush to repeal its height limits.

Cultural resistance to density remained strong, and developers continued to build outward rather than upward. But the technical argument had already been settled.

City Hall stood as living proof that:

- High-rise buildings could be engineered safely in Los Angeles

- Earthquakes were a challenge, not a barrier

- Fire, structural, and seismic risks could be managed

The height restriction was no longer about safety — it was about philosophy.

The Ironic Legacy

When Los Angeles finally lifted its height limit in 1957, the city did not suddenly erupt into skyscrapers. The habit of building outward was already deeply entrenched.

The result:

- A skyline that arrived decades late

- Uneven density across the region

- Multiple business centers instead of one core

- Housing and transit challenges baked into the city’s growth pattern

City Hall never triggered a skyscraper boom — but it quietly made one possible.

Why This Still Matters

Today, Los Angeles continues to wrestle with:

- Housing shortages

- Transit-oriented development debates

- Height and zoning battles near rail corridors

- Resistance to density in a growing city

These debates didn’t begin recently.

They trace back to a single contradiction: a city that banned tall buildings — while proving they could be built safely all along.

Los Angeles City Hall wasn’t just a monument.

It was a test case — and it passed.

Further Reading & Sources

- Los Angeles Department of City Planning – History of Urban Planning in LA

- Los Angeles Conservancy – History & Architecture of LA City Hall

- Water and Power Associates – Early Los Angeles Buildings & Height Limits

- USGS – How Buildings Are Designed to Withstand Earthquakes

- Los Angeles Department of Building and Safety – Building Code History

More from The Knowledge Series on STM Daily News

Discover more from Daily News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Knowledge

How a 22-year-old George Washington learned how to lead, from a series of mistakes in the Pennsylvania wilderness

This Presidents Day, I’ve been thinking about George Washington − not at his finest hour, but possibly at his worst.

Christopher Magra, University of Tennessee

This Presidents Day, I’ve been thinking about George Washington − not at his finest hour, but possibly at his worst.

In 1754, a 22-year-old Washington marched into the wilderness surrounding Pittsburgh with more ambition than sense. He volunteered to travel to the Ohio Valley on a mission to deliver a letter from Robert Dinwiddie, governor of Virginia, to the commander of French troops in the Ohio territory. This military mission sparked an international war, cost him his first command and taught him lessons that would shape the American Revolution.

As a professor of early American history who has written two books on the American Revolution, I’ve learned that Washington’s time spent in the Fort Duquesne area taught him valuable lessons about frontier warfare, international diplomacy and personal resilience.

The mission to expel the French

In 1753, Dinwiddie decided to expel French fur trappers and military forces from the strategic confluence of three mighty waterways that crisscrossed the interior of the continent: the Allegheny, Monongahela and Ohio rivers. This confluence is where downtown Pittsburgh now stands, but at the time it was wilderness.

King George II authorized Dinwiddie to use force, if necessary, to secure lands that Virginia was claiming as its own.

As a major in the Virginia provincial militia, Washington wanted the assignment to deliver Dinwiddie’s demand that the French retreat. He believe the assignment would secure him a British army commission.

Washington received his marching orders on Oct. 31, 1753. He traveled to Fort Le Boeuf in northwestern Pennsylvania and returned a month later with a polite but firm “no” from the French.

Dinwiddie promoted Washington from major to lieutenant colonel and ordered him to return to the Ohio River Valley in April 1754 with 160 men. Washington quickly learned that French forces of about 500 men had already constructed the formidable Fort Duquesne at the forks of the Ohio. It was at this point that he faced his first major test as a military leader. Instead of falling back to gather more substantial reinforcements, he pushed forward. This decision reflected an aggressive, perhaps naive, brand of leadership characterized by a desire for action over caution.

Washington’s initial confidence was high. He famously wrote to his brother that there was “something charming” in the sound of whistling bullets.

The Jumonville affair and an international crisis

Perhaps the most controversial moment of Washington’s early leadership occurred on May 28, 1754, about 40 miles south of Fort Duquesne. Guided by the Seneca leader Tanacharison – known as the “Half King” – and 12 Seneca warriors, Washington and his detachment of 40 militiamen ambushed a party of 35 French Canadian militiamen led by Ensign Joseph Coulon de Jumonville. The Jumonville affair lasted only 15 minutes, but its repercussions were global.

Ten of the French, including Jumonville, were killed. Washington’s inability to control his Native American allies – the Seneca warriors executed Jumonville – exposed a critical gap in his early leadership. He lacked the ability to manage the volatile intercultural alliances necessary for frontier warfare.

Washington also allowed one enemy soldier to escape to warn Fort Duquesne. This skirmish effectively ignited the French and Indian War, and Washington found himself at the center of a burgeoning international crisis.

Defeat at Fort Necessity

Washington then made the fateful decision to dig in and call for reinforcements instead of retreating in the face of inevitable French retaliation. Reinforcements arrived: 200 Virginia militiamen and 100 British regulars. They brought news from Dinwiddie: congratulations on Washington’s victory and his promotion to colonel.

His inexperience showed in his design of Fort Necessity. He positioned the small, circular palisade in a meadow depression, where surrounding wooded high ground allowed enemy marksmen to fire down with impunity. Worse still, Tanacharison, disillusioned with Washington’s leadership and the British failure to follow through with promised support, had already departed with his warriors weeks earlier. When the French and their Native American allies finally attacked on July 3, heavy rains flooded the shallow trenches, soaking gunpowder and leaving Washington’s men vulnerable inside their poorly designed fortification.

The battle of Fort Necessity was a grueling, daylong engagement in the mud and rain. Approximately 700 French and Native American allies surrounded the combined force of 460 Virginian militiamen and British regulars. Despite being outnumbered and outmaneuvered, Washington maintained order among his demoralized troops. When French commander Louis Coulon de Villiers – Jumonville’s brother – offered a truce, Washington faced the most humbling moment of his young life: the necessity of surrender. His decision to capitulate was a pragmatic act of leadership that prioritized the survival of his men over personal honor.

The surrender also included a stinging lesson in the nuances of diplomacy. Because Washington could not read French, he signed a document that used the word “l’assassinat,” which translates to “assassination,” to describe Jumonville’s death. This inadvertent admission that he had ordered the assassination of a French diplomat became propaganda for the French, teaching Washington the vital importance of optics in international relations.

Lessons that forged a leader

The 1754 campaign ended in a full retreat to Virginia, and Washington resigned his commission shortly thereafter. Yet, this period was essential in transforming Washington from a man seeking personal glory into one who understood the weight of responsibility.

He learned that leadership required more than courage – it demanded understanding of terrain, cultural awareness of allies and enemies, and political acumen. The strategic importance of the Ohio River Valley, a gateway to the continental interior and vast fur-trading networks, made these lessons all the more significant.

Ultimately, the hard lessons Washington learned at the threshold of Fort Duquesne in 1754 provided the foundational experience for his later role as commander in chief of the Continental Army. The decisions he made in Pennsylvania and the Ohio wilderness, including the impulsive attack, the poor choice of defensive ground and the diplomatic oversight, were the very errors he would spend the rest of his military career correcting.

Though he did not capture Fort Duquesne in 1754, the young George Washington left the woods of Pennsylvania with a far more valuable prize: the tempered, resilient spirit of a leader who had learned from his mistakes.

Christopher Magra, Professor of American History, University of Tennessee

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Dive into “The Knowledge,” where curiosity meets clarity. This playlist, in collaboration with STMDailyNews.com, is designed for viewers who value historical accuracy and insightful learning. Our short videos, ranging from 30 seconds to a minute and a half, make complex subjects easy to grasp in no time. Covering everything from historical events to contemporary processes and entertainment, “The Knowledge” bridges the past with the present. In a world where information is abundant yet often misused, our series aims to guide you through the noise, preserving vital knowledge and truths that shape our lives today. Perfect for curious minds eager to discover the ‘why’ and ‘how’ of everything around us. Subscribe and join in as we explore the facts that matter. https://stmdailynews.com/the-knowledge/

Discover more from Daily News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.