STM Blog

Vaccine mandates misinformation: 2 experts explain the true role of slavery and racism in the history of public health policy – and the growing threat ignorance poses today

Vaccine mandates misinformation: Florida’s vaccination rates decline as the state plans to eliminate mandates. Experts warn this could deepen health disparities, undermine public trust, and threaten community health, especially given the history of racism in vaccination practices.

Vaccine mandates misinformation:

Lauren MacIvor Thompson, Kennesaw State University and Stacie Kershner, Georgia State University

On Sept. 3, 2025, Florida announced its plans to be the first state to eliminate vaccine mandates for its citizens, including those for children to attend school.

Current Florida law and the state’s Department of Health require that children who attend day care or public school be immunized for polio, diphtheria, rubeola, rubella, pertussis and other communicable diseases. Dr. Joseph Ladapo, Florida’s surgeon general and a professor of medicine at the University of Florida, has stated that “every last one” of these decades-old vaccine requirements “is wrong and drips with disdain and slavery.”

As experts on the history of American medicine and vaccine law and policy, we took immediate note of Ladapo’s use of the word “slavery.”

There is certainly a complicated history of race and vaccines in the United States. But, in our view, invoking slavery as a way to justify the elimination of vaccines and vaccine mandates will accelerate mistrust and present a major threat to public health, especially given existing racial health disparities. It also erases Black Americans’ key work in centuries of American public health initiatives, including vaccination campaigns.

What’s clear: Vaccines and mandates save human lives

Evidence and data show that vaccines work, as do mandates, in keeping Americans healthy. The World Health Organization reported in a landmark 2024 study that vaccines have saved more than 154 million lives globally in just the past 50 years.

In the United States, vaccines for children are one of the top public health achievements of the 20th century. Rates of eight of the most common vaccine-preventable diseases in school-age children dropped by 97% or more from pre-vaccine levels, preventing an estimated 1,129,000 deaths and resulting in direct savings of US$540 billion and societal savings of $2.7 trillion.

History of vaccine mandates in the United States

Vaccine mandates in the United States date to the Colonial period and have a complex history. George Washington required his troops be inoculated, the predecessor of vaccination, against smallpox during the American Revolution.

To prevent outbreaks of this debilitating, disfiguring and deadly disease, state and local governments implemented smallpox inoculation and vaccination campaigns into the early 1900s. They targeted various groups, including enslaved people, immigrants, people living in tenement and other crowded housing conditions, manual laborers and others, forcibly vaccinating those who could not provide proof of prior vaccination.

Although religious exemptions were not recognized by law until the 1960s, some resisted these vaccination campaigns from the beginning, and 19th-century anti-vaccination societies urged the rollback of state laws requiring vaccination.

By the turn of the 20th century, however, the U.S. Supreme Court also began to intervene in matters of public health and vaccination. The court ultimately upheld vaccine mandates in Jacobson v. Massachusetts in 1905, in an effort to strike a balance between individual rights with the need to protect the public’s health. In Zucht v. King in 1922, the court also ruled in favor of vaccine mandates, this time for school attendance.

Vaccine mandates expanded by the middle of the 20th century to include vaccines for many dangerous childhood diseases, such as polio, measles, rubella and pertussis. When Jonas Salk’s polio vaccine became available, families waited in long lines for hours to receive it, hoping to prevent their children from having to experience paralysis or life in an iron lung.

Scientific studies in the 1970s demonstrated that state declines in measles cases were correlated with enforcement of school vaccine mandates. The federal Childhood Immunization Initiative launched in the late 1970s helped educate the public on the importance of vaccines and encouraged enforcement. All states had mandatory vaccine requirements for public school entry by 1980, and data over the past several decades continues to demonstrate the importance of these laws for public health.

Most parents also continue to support school mandates. A survey conducted in July and August 2025 by The Washington Post and the Kaiser Family Foundation finds that 81% of parents support laws requiring vaccines for school.

Black Americans’ long fight for public health equity

Despite the proven success of vaccines and the importance of vaccine mandates in maintaining high vaccination rates, there is a vocal anti-vaccine minority in the U.S. that has gained traction since the COVID-19 pandemic.

Misinformation proliferates both online and off. Some of the misinformation originates in the historical realities of vaccines and social policy in the United States.

When Ladapo, the Florida surgeon general, invoked the term “slavery” to refer to vaccine mandates, he may have been referring to the history of racism in the medical field, such as the U.S. Public Health Service Untreated Syphilis Study at Tuskegee. The study, which started in 1932 and spanned four decades, involved hundreds of Black men who were recruited without their knowledge or consent so that researchers could study the effects of untreated syphilis. Investigators misled the participants about the nature of the study and actively withheld treatment – including penicillin, which became the standard therapy in the late 1940s – in order to study the effects of untreated syphilis on the men’s bodies.

Today, the study is remembered as one of the most egregious instances of racism and unethical experimentation in American medicine. Its participants had enrolled in the study because it was advertised as a chance to receive expert medical care but, instead, were subjected to lies and painful “treatments.”

Despite these experiences in the medical system, Black Americans have long advocated for better health care, connecting it to the larger struggle for racial equality.

Vaccination is no exception. Despite the fact that they were often the subject of forced innoculation, enslaved people helped to lead the first American public health initiatives around epidemic disease. Historians’ research on smallpox and slavery, for example, has found that inoculation was widely accepted and practiced by West Africans by the early 1700s, and that enslaved people brought the practice to the Colonies.

Although his role is often downplayed, an African man known as Onesimus introduced his enslaver Cotton Mather to inoculation.

Throughout the next century, enslaved people often continued to inoculate each other to prevent smallpox outbreaks, and enslaved and free people of African descent played critical roles in keeping their own communities as healthy as possible in the face of violence, racism and brutality. The modern Civil Rights Movement explicitly drew on this history and centered health equity for Black Americans as one of its key tenets, including working to provide access to vaccines for preventable diseases.

In our view, Ladapo’s reference to vaccines as “slavery” ignores this important and nuanced history, especially Black Americans’ role in the history of preventing communicable disease with vaccines.

Lessons to learn from Tuskegee

Ladapo’s word choice also runs the risk of perpetuating the rightful mistrust that continues to exist in communities of color about vaccines and the American health system more broadly. Studies show that lingering effects of Tuskegee and other instances of medical racism have had real consequences for the health and vaccination rates of Black Americans.

A large body of evidence shows the existence of persistent health disparities for Black people in the United States compared with their white counterparts, leading to shorter lifespans, higher rates of maternal and infant mortality and higher rates of communicable and chronic diseases, with worse outcomes.

Eliminating vaccine mandates in Florida and expanding exemptions in other states will continue to widen these already existing disparities that stem from past public health wrongs.

There is an opportunity here, however, for health officials, not just in Florida but across the nation, to work together to learn from the past in making American public health better for everyone.

Rather than weakening vaccine mandates, national, state and local public health guidance can focus on expanding access and communicating trustworthy information about vaccines for all Americans. Policymakers can acknowledge the complicated history of vaccines, public health and race, while also recognizing how advancements in science and medicine have given us the opportunity to eradicate many of these diseases in the United States today.

Lauren MacIvor Thompson, Assistant Professor of History and Interdisciplinary Studies, Kennesaw State University and Stacie Kershner, Deputy Director of the Center for Law, Health & Society, Georgia State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The Bridge is a section of the STM Daily News Blog meant for diversity, offering real news stories about bona fide community efforts to perpetuate a greater good. The purpose of The Bridge is to connect the divides that separate us, fostering understanding and empathy among different groups. By highlighting positive initiatives and inspirational actions, The Bridge aims to create a sense of unity and shared purpose. This section brings to light stories of individuals and organizations working tirelessly to promote inclusivity, equality, and mutual respect. Through these narratives, readers are encouraged to appreciate the richness of diverse perspectives and to participate actively in building stronger, more cohesive communities.

https://stmdailynews.com/the-bridge

Discover more from Daily News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

unknown

Why people tend to believe UFOs are extraterrestrial

Last Updated on March 13, 2026 by Daily News Staff

Barry Markovsky, University of South Carolina

Most of us still call them UFOs – unidentified flying objects. NASA recently adopted the term “unidentified anomalous phenomena,” or UAP. Either way, every few years popular claims resurface that these things are not of our world, or that the U.S. government has some stored away.

I’m a sociologist who focuses on the interplay between individuals and groups, especially concerning shared beliefs and misconceptions. As for why UFOs and their alleged occupants enthrall the public, I’ve found that normal human perceptual and social processes explain UFO buzz as much as anything up in the sky.

Historical context

Like political scandals and high-waisted jeans, UFOs trend in and out of collective awareness but never fully disappear. Thirty years of polling find that 25%-50% of surveyed Americans believe at least some UFOs are alien spacecraft. Today in the U.S., over 100 million adults think our galactic neighbors pay us visits.

It wasn’t always so. Linking objects in the sky with visiting extraterrestrials has risen in popularity only in the past 75 years. Some of this is probably market-driven. Early UFO stories boosted newspaper and magazine sales, and today they are reliable clickbait online.

In 1980, a popular book called “The Roswell Incident” by Charles Berlitz and William L. Moore described an alleged flying saucer crash and government cover-up 33 years prior near Roswell, New Mexico. The only evidence ever to emerge from this story was a small string of downed weather balloons. Nevertheless, the book coincided with a resurgence of interest in UFOs. From there, a steady stream of UFO-themed TV shows, films, and pseudo-documentaries has fueled public interest. Perhaps inevitably, conspiracy theories about government cover-ups have risen in parallel.

Some UFO cases inevitably remain unresolved. But despite the growing interest, multiple investigations have found no evidence that UFOs are of extraterrestrial origin – other than the occasional meteor or misidentification of Venus.

But the U.S. Navy’s 2017 Gimbal video continues to appear in the media. It shows strange objects filmed by fighter jets, often interpreted as evidence of alien spacecraft. And in June 2023, an otherwise credible Air Force veteran and former intelligence officer made the stunning claim that the U.S. government is storing numerous downed alien spacecraft and their dead occupants. https://www.youtube.com/embed/2TumprpOwHY?wmode=transparent&start=0 UFO videos released by the U.S. Navy, often taken as evidence of alien spaceships.

Human factors contributing to UFO beliefs

Only a small percentage of UFO believers are eyewitnesses. The rest base their opinions on eerie images and videos strewn across both social media and traditional mass media. There are astronomical and biological reasons to be skeptical of UFO claims. But less often discussed are the psychological and social factors that bring them to the popular forefront.

Many people would love to know whether or not we’re alone in the universe. But so far, the evidence on UFO origins is ambiguous at best. Being averse to ambiguity, people want answers. However, being highly motivated to find those answers can bias judgments. People are more likely to accept weak evidence or fall prey to optical illusions if they support preexisting beliefs.

For example, in the 2017 Navy video, the UFO appears as a cylindrical aircraft moving rapidly over the background, rotating and darting in a manner unlike any terrestrial machine. Science writer Mick West’s analysis challenged this interpretation using data displayed on the tracking screen and some basic geometry. He explained how the movements attributed to the blurry UFO are an illusion. They stem from the plane’s trajectory relative to the object, the quick adjustments of the belly-mounted camera, and misperceptions based on our tendency to assume cameras and backgrounds are stationary.

West found the UFO’s flight characteristics were more like a bird’s or a weather balloon’s than an acrobatic interstellar spacecraft. But the illusion is compelling, especially with the Navy’s still deeming the object unidentified.

West also addressed the former intelligence officer’s claim that the U.S. government possesses crashed UFOs and dead aliens. He emphasized caution, given the whistleblower’s only evidence was that people he trusted told him they’d seen the alien artifacts. West noted we’ve heard this sort of thing before, along with promises that the proof will soon be revealed. But it never comes.

Anyone, including pilots and intelligence officers, can be socially influenced to see things that aren’t there. Research shows that hearing from others who claim to have seen something extraordinary is enough to induce similar judgments. The effect is heightened when the influencers are numerous or higher in status. Even recognized experts aren’t immune from misjudging unfamiliar images obtained under unusual conditions.

Group factors contributing to UFO beliefs

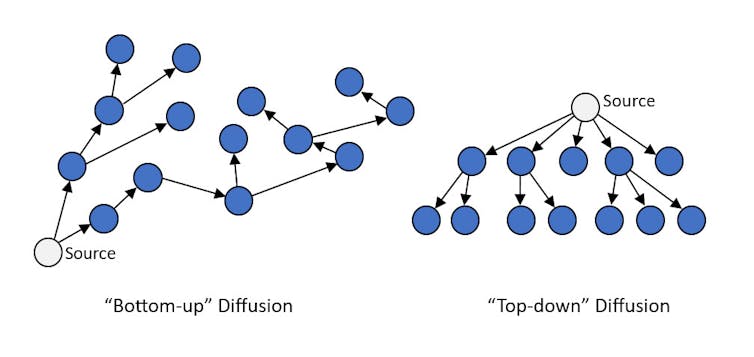

“Pics or it didn’t happen” is a popular expression on social media. True to form, users are posting countless shaky images and videos of UFOs. Usually they’re nondescript lights in the sky captured on cellphone cameras. But they can go viral on social media and reach millions of users. With no higher authority or organization propelling the content, social scientists call this a bottom-up social diffusion process.

In contrast, top-down diffusion occurs when information emanates from centralized agents or organizations. In the case of UFOs, sources have included social institutions like the military, individuals with large public platforms like U.S. senators, and major media outlets like CBS.

Amateur organizations also promote active personal involvement for many thousands of members, the Mutual UFO Network being among the oldest and largest. But as Sharon A. Hill points out in her book “Scientifical Americans,” these groups apply questionable standards, spread misinformation and garner little respect within mainstream scientific communities.

Top-down and bottom-up diffusion processes can combine into self-reinforcing loops. Mass media spreads UFO content and piques worldwide interest in UFOs. More people aim their cameras at the skies, creating more opportunities to capture and share odd-looking content. Poorly documented UFO pics and videos spread on social media, leading media outlets to grab and republish the most intriguing. Whistleblowers emerge periodically, fanning the flames with claims of secret evidence.

Despite the hoopla, nothing ever comes of it.

For a scientist familiar with the issues, skepticism that UFOs carry alien beings is wholly separate from the prospect of intelligent life elsewhere in the universe. Scientists engaged in the search for extraterrestrial intelligence have a number of ongoing research projects designed to detect signs of extraterrestrial life. If intelligent life is out there, they’ll likely be the first to know.

As astronomer Carl Sagan wrote, “The universe is a pretty big place. If it’s just us, seems like an awful waste of space.”

Barry Markovsky, Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Sociology, University of South Carolina

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The science section of our news blog STM Daily News provides readers with captivating and up-to-date information on the latest scientific discoveries, breakthroughs, and innovations across various fields. We offer engaging and accessible content, ensuring that readers with different levels of scientific knowledge can stay informed. Whether it’s exploring advancements in medicine, astronomy, technology, or environmental sciences, our science section strives to shed light on the intriguing world of scientific exploration and its profound impact on our daily lives. From thought-provoking articles to informative interviews with experts in the field, STM Daily News Science offers a harmonious blend of factual reporting, analysis, and exploration, making it a go-to source for science enthusiasts and curious minds alike. https://stmdailynews.com/category/science/

Discover more from Daily News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Knowledge

How Water Towers Work: The Simple System That Keeps Water Flowing in American Cities

Learn how water towers work in the United States, why they are so tall, and how gravity helps cities maintain water pressure and emergency water supplies.

How Water Towers Work

Water towers are one of the most recognizable pieces of infrastructure across the United States. Rising above towns, suburbs, and cities, these elevated tanks quietly perform a vital function every day: maintaining water pressure and storing emergency water for local communities.

Although they may look simple, water towers are an essential part of modern municipal water systems and remain one of the most reliable ways to deliver water to homes and businesses.

The Basic Science Behind Water Towers

Water towers work using a simple principle of physics: gravity.

Water from treatment plants or underground wells is pumped into a storage tank located high above the ground—typically between 100 and 200 feet tall. Because the tank is elevated, gravity naturally pushes the water downward through the city’s pipeline network.

This gravitational force creates the water pressure needed to supply homes, businesses, irrigation systems, and fire hydrants throughout the community.

Most residential plumbing systems in the United States operate best at 40 to 60 PSI (pounds per square inch), which water towers can easily provide through elevation alone.

Why Water Towers Are Built So Tall

The height of a water tower determines how much pressure it can create. Engineers use a common rule:

For example, a water tower standing 120 feet tall can generate roughly 50 PSI of pressure—perfect for delivering water throughout a residential neighborhood.

Why Cities Still Use Water Towers

While modern pumping systems could theoretically move water through pipes continuously, water towers provide several major advantages that make them a preferred design in many municipal systems.

- Stable Water Pressure – Water towers maintain consistent pressure even during peak usage times.

- Energy Efficiency – Pumps can refill towers overnight when electricity demand is lower.

- Emergency Water Supply – If power fails, gravity can continue delivering water.

- Fire Protection – Fire hydrants depend on strong, immediate water pressure.

The Daily Fill-and-Use Cycle

Water towers typically operate on a daily cycle based on community demand.

- Night: Pumps refill the tower while water demand is low.

- Morning: Water levels drop as residents shower and prepare for the day.

- Daytime: Businesses and homes continue drawing water from the tower.

- Evening: The system begins refilling the tank for the next day.

How Much Water Can a Tower Store?

Water towers come in many sizes depending on the population they serve.

- Small towns: 50,000–300,000 gallons

- Suburban communities: 500,000–1 million gallons

- Larger urban systems: up to 2 million gallons or more

Even a single tower holding one million gallons can supply thousands of homes for several hours during peak demand or emergencies.

Modern Technology Inside Water Towers

Today’s water towers are equipped with advanced monitoring systems that help utilities maintain safe and reliable water supplies.

- Digital water level sensors

- Automated pump controls

- Water quality monitoring

- Protective interior coatings

- Regular inspections and maintenance

Landmarks in the American Skyline

Many cities turn their water towers into local landmarks by painting them with city names, mascots, or community slogans. Some towns even design towers shaped like giant objects such as fruit, coffee cups, or sports balls.

Despite their distinctive appearance, water towers remain one of the simplest and most reliable engineering solutions for delivering clean water to millions of Americans every day.

Next time you see a water tower rising above a town skyline, remember: it’s not just a landmark—it’s the gravity-powered system that keeps water flowing.

Related External Coverage

For more information about how water towers and municipal water systems work, explore the following resources:

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency – Drinking Water Regulations

- American Water Works Association – Water Storage and Water Towers

- HowStuffWorks – How Water Distribution Systems Work

- U.S. Geological Survey – Drinking Water and Groundwater Basics

- U.S. Department of Energy – How Water Towers Work

Dive into “The Knowledge,” where curiosity meets clarity. This playlist, in collaboration with STMDailyNews.com, is designed for viewers who value historical accuracy and insightful learning. Our short videos, ranging from 30 seconds to a minute and a half, make complex subjects easy to grasp in no time. Covering everything from historical events to contemporary processes and entertainment, “The Knowledge” bridges the past with the present. In a world where information is abundant yet often misused, our series aims to guide you through the noise, preserving vital knowledge and truths that shape our lives today. Perfect for curious minds eager to discover the ‘why’ and ‘how’ of everything around us. Subscribe and join in as we explore the facts that matter. https://stmdailynews.com/the-knowledge/

Discover more from Daily News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

unknown

The Unfavorable Semicircle Mystery: The YouTube Channel That Uploaded Tens of Thousands of Cryptic Videos

In 2015, the YouTube channel Unfavorable Semicircle gained attention for its enigmatic and abundant video uploads, totaling over 70,000 before its deletion in 2016. Theories about its purpose vary, from automated content generation to digital art experimentation, leaving its intent unresolved.

In the vast digital landscape of the internet, strange phenomena occasionally emerge that leave investigators, tech enthusiasts, and everyday viewers scratching their heads. One of the most puzzling cases appeared in 2015, when a mysterious YouTube channel called Unfavorable Semicircle began uploading an astonishing number of cryptic videos.

Within months, the channel had published tens of thousands of bizarre clips, many of which seemed random, incomprehensible, and visually chaotic. But as internet detectives began analyzing the content more closely, they discovered that these videos might not have been random at all.

The Sudden Appearance of an Internet Mystery

The Unfavorable Semicircle channel reportedly appeared in March 2015, with its first uploads arriving in early April.

Almost immediately, the channel began publishing videos at an incredible pace. Observers estimated that the account uploaded thousands of videos per week, sometimes multiple videos per minute. By the time the channel disappeared in early 2016, researchers believed it had uploaded well over 70,000 videos, possibly far more.

The scale alone made the project seem impossible for a human to manage manually.

Strange Visuals and Cryptic Titles

Most of the videos shared similar characteristics:

- Extremely short or very long runtime

- Abstract visuals such as flashing colors, static, or distorted imagery

- Little or no audio, or heavily distorted sounds

- Titles made of random characters, symbols, or numbers

To casual viewers, the videos looked like pure digital noise. However, online investigators suspected something more deliberate was happening.

Hidden Images Discovered

The mystery deepened when researchers began extracting individual frames from some videos.

When thousands of frames from certain clips were stitched together, the results sometimes formed coherent images. One of the most famous examples involved a video titled “LOCK.” While the footage appeared chaotic at first, combining the frames revealed a recognizable composite image.

This discovery suggested the videos were carefully constructed rather than random uploads.

Theories About the Channel’s Purpose

Because the creator never explained the project, several theories emerged across Reddit, YouTube, and internet forums.

Automated Experiment

Many believe the channel was created using automated software that generated and uploaded content at scale.

Alternate Reality Game (ARG)

Some viewers suspected the channel might be part of a hidden puzzle or digital scavenger hunt.

Encrypted Communication

Others compared the channel to Cold War “numbers stations,” suggesting the videos could contain coded messages.

Digital Art Project

Another theory suggests the channel was an experimental art project exploring algorithms, data, and visual noise.

Despite years of investigation, no single explanation has been confirmed.

Why the Channel Disappeared

In February 2016, YouTube removed the channel, reportedly due to spam or automated activity violations.

By that time, the channel had already become a minor internet legend. Fortunately, some researchers managed to archive a large portion of the videos before they disappeared.

Even today, archived clips continue to circulate online as investigators attempt to decode them.

Other Mysterious YouTube Channels

The Unfavorable Semicircle mystery is not the only strange case on YouTube.

One well-known example is Webdriver Torso, a channel that uploaded hundreds of thousands of videos showing red and blue rectangles with simple beeping sounds. Internet speculation ran wild before Google eventually confirmed it was an internal YouTube testing account.

Another example is AETBX, which posts distorted visuals and unusual audio that some viewers believe contain hidden patterns or encoded information.

These cases highlight how automation, experimentation, and creativity can sometimes blur the line between technology and mystery.

A Digital Mystery That Remains Unsolved

Nearly a decade later, the true purpose behind Unfavorable Semicircle remains unknown.

Was it a sophisticated experiment? A piece of algorithmic art? Or simply an automated test that accidentally captured the internet’s imagination?

Whatever the explanation, the channel stands as a reminder that even in a world filled with billions of videos and endless information, the internet can still produce mysteries that challenge our understanding of technology.

Why Internet Mysteries Still Fascinate Us

Stories like Unfavorable Semicircle capture attention because they combine technology, creativity, and the unknown. They invite people from around the world to collaborate, analyze patterns, and search for meaning hidden in the noise.

And sometimes, the most intriguing part of the mystery is that the answer may never fully be known.

Related Coverage & Further Reading

- Atlas Obscura – The Unsettling Mystery of the Creepiest Channel on YouTube

- Her Campus – Top 5 Most Obscure Internet Mysteries

- Medium – Unfavorable Semicircle: The YouTube Mystery No One Can Solve

- Gazette Review – Top 10 Strangest YouTube Channels Ever

- Decoding the Unknown – Unfavorable Semicircle YouTube Mystery Archive

- Wikipedia – Unfavorable Semicircle

Dive into “The Knowledge,” where curiosity meets clarity. This playlist, in collaboration with STMDailyNews.com, is designed for viewers who value historical accuracy and insightful learning. Our short videos, ranging from 30 seconds to a minute and a half, make complex subjects easy to grasp in no time. Covering everything from historical events to contemporary processes and entertainment, “The Knowledge” bridges the past with the present. In a world where information is abundant yet often misused, our series aims to guide you through the noise, preserving vital knowledge and truths that shape our lives today. Perfect for curious minds eager to discover the ‘why’ and ‘how’ of everything around us. Subscribe and join in as we explore the facts that matter. https://stmdailynews.com/the-knowledge/

Discover more from Daily News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.