Nina Fontana, CC BY-NC-ND

What Native-held lands in California can teach about resilience and the future of wildfire

Nina Fontana, University of California, Davis and Beth Rose Middleton Manning, University of California, Davis

It took decades, stacks of legal paperwork and countless phone calls, but, in the spring of 2025, a California Chuckchansi Native American woman and her daughter walked onto a 5-acre parcel of land, shaded by oaks and pines, for the first time.

This land near the foothills of the Sierra National Forest is part of an unusual category of land that has been largely left alone for more than a century. The parcel, like roughly 400 other parcels across the state totaling 16,000 acres in area, is held in trust by the federal government for the benefit of specific Indigenous people – such as a family member of the woman visiting the land with her daughter.

Largely inaccessible for more than a century, and therefore so far of little actual benefit to those it is meant for, this land provides an opportunity for Indigenous people to not only have recognized land rights but also to care for their land in traditional ways that could help reduce the threat of intensifying wildfires as part of a changing climate.

In collaboration with families who have long been connected to this land, our research team at the University of California, Davis is working to clarify ownership records, document ecological conditions and share information to help allottees access and use their allotments.

California’s unique historical situation

As European nations colonized the area that became the United States, they entered into treaties with Native nations. These treaties established tribal reservations and secured some Indigenous rights to resources and land.

Just after California became a state in 1850, the federal government negotiated 18 treaties with 134 tribes, reserving about 7.5 million acres, roughly 7.5% of the state, for tribes’ exclusive use.

However, land speculators and early state politicians considered the land too valuable to give away, so the U.S. Senate refused to ratify the treaties – while allowing the tribes to think they were valid and legally binding. As a result, most California Native Americans were left landless and subject to violent, state-sanctioned removals by incoming miners and settlers.

Then, in 1887, Congress passed the Dawes Act, which allowed Native people across the U.S. to be assigned or apply for land individually. Though it called the seized land – their former tribal homelands – the “public domain,” the Dawes Act presented a significant opportunity for the landless Native people in California to secure land rights that would be recognized by the government.

These land parcels, called allotments, are not private land, public land or reservation land – rather, they are individual parcels held in trust by the federal government for the benefit of allottees and their descendants.

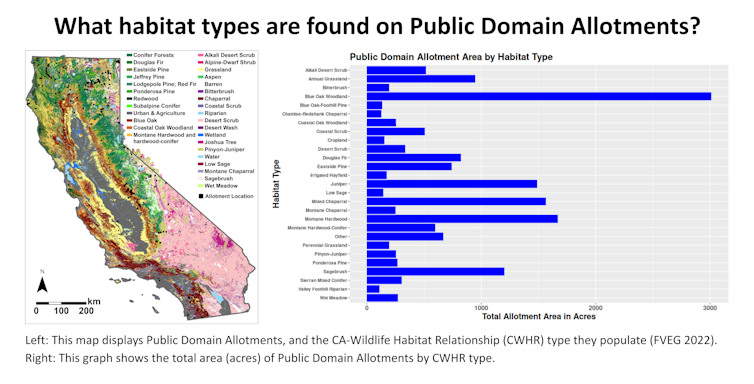

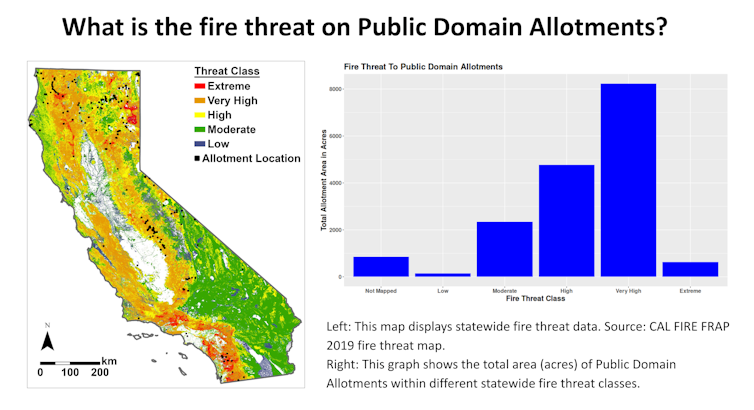

Images created by James Thorne, Ryan Boynton, Allan Hollander and Dave Waetjan.

Many of these allotments were remote – ecologically rich, yet hard to access. They were carved out of ancestral territories but often lacked access to infrastructure like roads, water or electricity. In some cases, allotments were separated from traditional village sites, ceremonial areas or vital water resources, cutting them off from broader ecosystems and community networks.

Federal officials often drew rough or incorrect maps and even lost track of which parcels had been allotted and to whom, especially as original allottees passed away. As a result, many allotments were claimed and occupied by others, coming into private hands without the full knowledge or consent of the Native families they were held in trust for.

There were once 2,522 public domain allotments in California totaling 336,409 acres. In 2025, approximately 400 of these allotments remain, encompassing just over 16,000 acres. They are some of the only remaining, legally recognized tracts of land where California Native American families can maintain ties to place, which make them uniquely significant for cultural survival, sovereignty and ecological stewardship.

The allotments today

Because of their remoteness, many of these lands remained relatively undisturbed by human activity and are home to diverse habitats, native plants and traditional gathering places. And because they are held in trust for Native people, they present an opportunity to exercise Indigenous practices of land and resource management, which have sustained people and ecosystems through millennia of climate shifts.

We and our UC Davis research team partner with allottee families; legal advocates including California Indian Legal Services, a Native-led legal nonprofit; and California Public Domain Allottee Association, an allottee-led nonprofit that supports allottees to access and care for their lands. Together, we are studying various aspects of the remaining allotments, including seeking to understand how vulnerable they are to wildfire and drought, and identifying options for managing the land to reduce those vulnerabilities.

Images created by James Thorne, Ryan Boynton, Allan Hollander and Dave Waetjan.

An opportunity for learning

So far, our surveys of the vegetation on these lands suggest that they could serve as places that sustain both flora and fauna as the climate changes.

Many of these parcels are located in remote, less-developed foothills or steep terrain where they have remained relatively intact, retaining more native species and diverse habitats than surrounding lands. Many of these parcels have elements like oak woodlands, meadows, brooks and rivers that create cooler, wetter areas that help plants and animals endure wildfires or periods of extreme heat or drought.

Allotment lands also offer the potential for the return of stewardship methods that – before European colonization – sustained and improved these lands for generations. For example, Indigenous communities have long used fire to tend plants, reduce overgrowth, restore water tables and generally keep ecosystems healthy.

Guided by Indigenous knowledge and rooted in the specific cultures and ecologies of place, this practice, often called cultural burning, reduces dry materials that could fuel future wildfires, making landscapes more fire-resilient and lowering both ecological and economic damage when wildfires occur. At the same time, it brings back plants for food, medicine, fiber and basketry for California Native communities.

Challenges on allotments

The Chuckchansi family who reached their land for the first time in the spring of 2025 would like to move onto the land. However, the parcel is surrounded by private property, and they need to seek permission from neighboring landowners to even walk onto their own parcel.

In addition, a small number of employees at the Bureau of Indian Affairs are responsible for allotments, and they must also deal with issues on larger reservations and other tribal lands.

Further, because the lands are held in federal trust, allottees’ ability to engage in traditional management practices like cultural burning often face more stringent federal permitting processes than state or private landowners – including restrictions under the Clean Air Act and the National Environmental Policy Act.

To our knowledge, no fire management plans have been approved by the Bureau of Indian Affairs on California Native American public domain allotments. Nonetheless, many families are interested in following traditional practices to manage their land. These efforts were a key topic at the most recent California Public Domain Allottees Conference, which included about 100 participants, including many allottee families.

Nina Fontana, CC BY-NC-ND

Why it matters

As California searches for ideas to help its people adapt to climate change, the allotment lands offer what we believe is a meaningful opportunity to elevate Indigenous leadership in climate adaptation. Indigenous land stewardship strategies have shown they can reduce wildfire risk, restoring ecosystems and sustaining culturally important plants and foods. Though the parcels are small, the practices applied there – such as cultural burning, selective gathering and water stewardship – are often low-cost, community-based and potentially adaptable to larger parcels elsewhere around the state.

One option could be to shift some of the regulatory authority from the Bureau of Indian Affairs to the allottees themselves. Shifting authority to Indigenous peoples has improved forest health elsewhere, as found in a collaborative study between University of California Extension foresters and Hoopa Tribal Forestry. That research found that when the Hoopa Tribe gained control of forestry on their reservation along the Trinity River in northern California, tribal leaders moved toward more restorative forestry practices. They decreased allowable logging amounts, created buffers around streams and protected species that were culturally important, while still reducing the buildup of downed or dead wood that can fuel wildfires.

At a time when California faces record-breaking wildfires and intensifying climate extremes, allotments offer rare pockets of intact habitat with the potential to be managed with cultural knowledge and ecological care. They show that adapting to change is not just about infrastructure or technology, but also about relationships – between people and place, culture and ecology, past and future.

Kristin Ruppel from Montana State University, author of “Unearthing Indian Land, and Jay Petersen from California Indian Legal Services also contributed to the drafting of this article.

Nina Fontana, Researcher in Native American Studies, University of California, Davis and Beth Rose Middleton Manning, Professor of Native American Studies, University of California, Davis

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Sinking Cities: Why Parts of Phoenix—and Much of Urban America—Are Slowly Dropping