How many types of insects are there in the world? – Sawyer, age 8, Fuquay-Varina, North Carolina

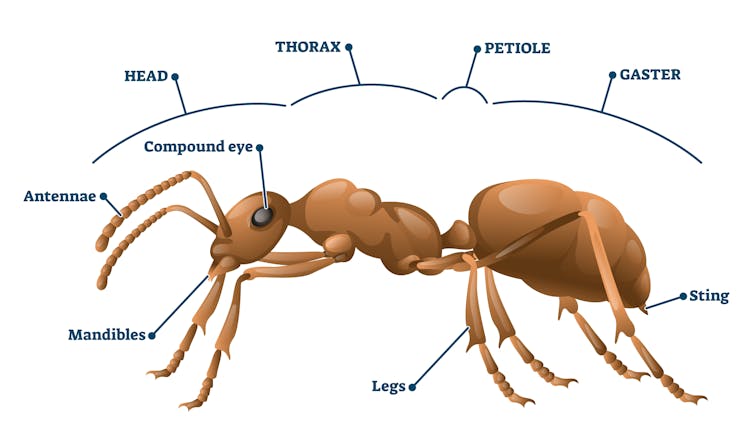

Exploring anywhere on Earth, look closely and you’ll find insects. Check your backyard and you may see ants, beetles, crickets, wasps, mosquitoes and more. There are more kinds of insects than there are mammals, birds and plants combined. This fact has fascinated scientists for centuries. One of the things biologists like me do is classify all living things into categories. Insects belong to a phylum called Arthropoda – animals with hard exoskeletons and jointed feet. All insects are arthropods, but not all arthropods are insects. For instance, spiders, lobsters and millipedes are arthropods, but they’re not insects. Instead, insects are a subgroup within Arthropoda, a class called “Insecta,” that is characterized by six legs, two antennae and three body segments – head, abdomen and the thorax, which is the part of the body between the head and abdomen.

What is a species?

All insects descend from a common ancestor that lived about about 480 million years ago. For context, that’s about 100 million years before any of our vertebrate ancestors – animals with a backbone – ever walked on land. A species is the most basic unit that biologists use to classify living things. When people use words like “ant” or “fly” or “butterfly” they are referring not to species, but to categories that may contain hundreds, thousands or tens of thousands of species. For example, about 18,000 species of butterfly exist – think monarch, zebra swallowtail or cabbage white. Basically, species are a group that can interbreed with each other, but not with other groups. One obvious example: bees can’t interbreed with ants. But brown-belted bumblebees and red-belted bumblebees can’t interbreed either, so they are different species of bumblebee. Each species has a unique scientific name – like Bombus griseocollis for the brown-belted bumblebee – so scientists can be sure which species they’re talking about.

Quadrillions of ants

Counting the exact number of insect species is probably impossible. Every year, some species go extinct, while some evolve anew. Even if we could magically freeze time and survey the entire Earth all at once, experts would disagree on the distinctiveness or identity of some species. So instead of counting, researchers use statistical analysis to make an estimate. One scientist did just that. He published his answer in a 2018 research paper. His calculations showed there are approximately 5.5 million insect species, with the correct number almost certainly between 2.6 and 7.2 million. Beetles alone account for almost one-third of the number, about 1.5 million species. By comparison, there are “only” an estimated 22,000 species of ants. This and other studies have also estimated about 3,500 species of mosquitoes, 120,000 species of flies and 30,000 species of grasshoppers and crickets. The estimate of 5.5 million species of insects is interesting. What’s even more remarkable is that because scientists have found only about 1 million species, that means more than 4.5 million species are still waiting for someone to discover them. In other words, over 80% of the Earth’s insect biodiversity is still unknown. Add up the total population and biomass of the insects, and the numbers are even more staggering. The 22,000 species of ants comprise about 20,000,000,000,000,000 individuals – that’s 20 quadrillion ants. And if a typical ant weighs about 0.0001 ounces (3 milligrams) – or one ten-thousandth of an ounce – that means all the ants on Earth together weigh more than 132 billion pounds (about 60 billion kilograms). That’s the equivalent of about 7 million school buses, 600 aircraft carriers or about 20% of the weight of all humans on Earth combined.Many insect species are going extinct

All of this has potentially huge implications for our own human species. Insects affect us in countless ways. People depend on them for crop pollination, industrial products and medicine. Other insects can harm us by transmitting disease or eating our crops. Most insects have little to no direct impact on people, but they are integral parts of their ecosystems. This is why entomologists – bug scientists – say we should leave insects alone as much as possible. Most of them are harmless to people, and they are critical to the environment. It is sobering to note that although millions of undiscovered insect species may be out there, many will go extinct before people have a chance to discover them. Largely due to human activity, a significant proportion of Earth’s biodiversity – including insects – may ultimately be forever lost.Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live. And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best. Nicholas Green, Assistant Professor of Biology, Kennesaw State University This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.