Entertainment

Remembering Angela Lansbury (MSNBC)

Star of the screen and stage, Angela Lansbury has passed away at 96 years old.

Star of the screen and stage, Angela Lansbury has passed away at 96 years old. We take a look back at her decades in entertainment.

Dame Angela Brigid Lansbury DBE (16 October 1925 – 11 October 2022) was an Irish-British -American actress and singer who played various roles across film, stage, and television. Her career, one of the longest in the entertainment industry,[citation needed] spanned eight decades, much of it in the United States; her work also received much international attention. She was one of the last surviving stars from the Golden Age of Hollywood cinema at the time of her death. Throughout her life, she received an Honorary Oscar Award, 3 Oscar nominations, 18 Emmy nominations, 1 Grammy nomination, 6 Golden Globe Awards, and 5 Tony Awards, plus the Lifetime Achievement Tony Award in 2022.

Lansbury was born to an upper-middle-class family in central London, the daughter of Irish actress Moyna Macgill and English politician Edgar Lansbury. To escape the Blitz, she moved to the United States in 1940, studying acting in New York City. Proceeding to Hollywood in 1942, she signed to MGM and obtained her first film roles, in Gaslight (1944), National Velvet (1944), and The Picture of Dorian Gray (1945), earning her two Academy Award nominations and a Golden Globe Award. She appeared in eleven further MGM films, mostly in minor roles, and after her contract ended in 1952 she began supplementing her cinematic work with theatrical appearances. Although largely seen as a B-list star during this period, her role in the film The Manchurian Candidate (1962) received widespread acclaim and is often cited as one of her career-best performances, earning her a third Academy Award nomination. Moving into musical theatre, Lansbury finally gained stardom for playing the leading role in the Broadway musical Mame (1966), which won her her first Tony Award and established her as a gay icon.

Amidst difficulties in her personal life, Lansbury moved from California to County Cork, Ireland in 1970, and continued with a variety of theatrical and cinematic appearances throughout that decade. These included leading roles in the stage musicals Gypsy, Sweeney Todd, and The King and I, as well as in the hit Disney film Bedknobs and Broomsticks (1971). Moving into television in 1984, she achieved worldwide fame as fictional writer and sleuth Jessica Fletcher in the American whodunit series Murder, She Wrote, which ran for twelve seasons until 1996, becoming one of the longest-running and most popular detective drama series in television history. Through Corymore Productions, a company that she co-owned with her husband Peter Shaw, Lansbury assumed ownership of the series and was its executive producer for the final four seasons. She also moved into voice work, contributing to animated films like Disney’s Beauty and the Beast (1991) and Don Bluth‘s Anastasia (1997). She toured in a variety of international productions and continued to make occasional film appearances such as Nanny McPhee (2005) and Mary Poppins Returns (2018).

Lansbury received an Honorary Academy Award, a Lifetime Achievement Award from the BAFTA, a Lifetime Achievement Tony Award and five additional Tony Awards, six Golden Globes, and an Olivier Award. She also was nominated for numerous other industry awards, including the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress on three occasions, and various Primetime Emmy Awards on 18 occasions, and a Grammy Award. In 2014, Lansbury was made a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire by Queen Elizabeth II. She was the subject of three biographies. (wikipedia)

- Introducing the Newest Powerhouse in Pro Pickleball: The Columbus HotShots“Discover the excitement as the Columbus HotShots bring a new level of competition to pro pickleball, raising the stakes and igniting the courts! #Pickleball #ProPickleball”

- Limited-Time Offer: Dive into Fallout’s World with Grubhub’s Nuka-Blast Burger!“Grubhub debuts the Nuka-Blast Burger Meal to celebrate the series premiere of Fallout on Prime Video. Spice up your meal and join the Fallout universe!”

- SPACEMOB Expands Reach Into Sports Programming, Live EventsOVERLAND PARK, Kan., April 5, 2024 /PRNewswire/ — SPACEMOB, the global media company focused on distributing streaming content and FAST channels, is gearing up for an exhilarating year of sports entertainment. With an eye on the future, SPACEMOB is poised to revolutionize the streaming landscape with its pioneering approach to sports programming. In the coming year, SPACEMOB will… Read more: SPACEMOB Expands Reach Into Sports Programming, Live Events

- Angeline Pompei Releases Vocabulary Word Search Book for Portuguese SpeakersNew ‘Learn English Fast’ bilingual book engages Portuguese-speaking adults through activity-based methods.

- City Hunter Live-Action Trailer: A Thrilling Adaptation of the Legendary Manga Sets the Stage“Get ready for the eagerly awaited live-action adaptation of City Hunter! The newly released trailer showcases adventure, danger, and an unlikely bond. Don’t miss out on the excitement!”

Senior Pickleball Report

Introducing the Newest Powerhouse in Pro Pickleball: The Columbus HotShots

“Discover the excitement as the Columbus HotShots bring a new level of competition to pro pickleball, raising the stakes and igniting the courts! #Pickleball #ProPickleball”

In the latest episode of Sleeve’s Senior Pickleball Report’s podcast, “People of Pickleball,” host Mike “Sleeves” Sliwa sits down with Jeff McKnight, co-owner of the recently established Columbus HotShots in the National Pickleball League. This intriguing conversation uncovers the unique journey and vision behind the formation of the team. Although this brief highlight leaves much to the imagination, it certainly sparks anticipation and curiosity. Tune in to the episode to delve deeper into the world of pickleball and discover the fascinating stories of the People of Pickleball.

Columbus HotShots

Instagram:

@columbushotshots

Facebook:

https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=61556078372038

Sleeve’s SPR on the web:

https://stmdailynews.com/sleeves-senior-pickleball-report/

Sign up for the SPR Newsletter and get news and episode release info right into your inbox: https://stmdailynews.com/sleeves-senior-pickleball-report/sleeves-spr-newsletter-sign-up/

Merch links and affiliate links…

Looking for great deals on the products we’ve reviewed? Head over to our affiliates and partner page now and take advantage of the amazing discounts we’ve secured for you. Don’t miss out on this opportunity to save big! https://stm-store.online/spr-affiliates-and-partners/

Crown Pickleball: Get 15% off your purchase by using my discount code: MICHAELSLIWA15

https://crownpickleball.store/michaelsliwa

GOSleeves Kinesiology Sleeves

https://gokinesiologysleeves.com

Promo Code: SLEEVESSPR for 15% off

Brioti Eyewear

Promo Code:SLEEVES10 for 10% off

Hesacore Grips

https://shop.hesacore.com/discount/SLEEVES10?ref=tvolvibq

Promo Code: SLEEVES10 for 10% off

Luxe PB

https://luxepickleball.com/?ref=napvyzwo

promo code: MICHAELJSLIWA

for 15% off

Aethos PB

Promo code: SLEEVES for 10% off

GoSleeves

https://gokinesiologysleeves.com

Promo code: SLEEVESSPR for 15% off

https://www.ethospickleball.com

SLEEVES 20 for 20% off

Wowlly PB

WOWLLYSPR for 10% off

TMPR SPORTS

DISCOUNT CODE: SPR20 for $20 off+ FREE SHIPPING

OM Pickleball

promo code: OMxSLEEVES for 10% off + Free shipping

Wickle Elite 1: A Game-Changing Pickleball Paddle

Describing the paddle as a game-changer, Sliwa went as far as suggesting that the sport itself should consider rebranding to “Wickleball” in honor of this groundbreaking equipment. With a low price tag that won’t leave your wallet in a pickle, the Wickle Elite 1 promises to elevate your pickleball experience without breaking the bank.

Check out the Wickle product line and get 10% off your purchase ( use the code sleeves10): https://wicklesports.com?sca_ref=4259414.aeWn90ZVTe

Visit Miles Jane and get $15 off by using code SLEEVES15OFF when you make a purchase.

MilesJane on Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/milesjane_pickleball/

#PickleballFashion

Discover the newest apparel and accessories for the Senior Pickleball Report by SLEEVES, now available through Santa Barbara Happy! Use the discount code: Sleeve10 for 10% off.

PiklNation: We believe that pickleball is not just a game, but a lifestyle. Our mission is to add joy, style, and humor to the pickleball community. https://www.piklnation.com/

Check out the Bread & Butter Filth and get 10% off your purchase ( use the code SleevesPBR):

https://breadbutterpickleballco.sjv.io/213j6A

Picklin is revolutionizing pickleball practice with The Dink Net! Improve your dink game and revolutionize your practice with this portable net that sets up in under 60 seconds. Perfect for practicing your skills anywhere, The Dink Net enhances muscle memory and helps you become an expert player faster. Picklin is dedicated to enhancing your game with innovative products, ensuring your transition into pickleball is smooth and enjoyable.

Use code SENIORPICKLEBALLREPORT for 10% off your entire order. Elevate your pickleball experience with Picklin! https://startpicklin.com/seniorpickleballreport

Fitville is offering a discount to you, the viewers of Sleeve’s SPR… Use this code to get 30% off: SPR30

https://shareasale.com/r.cfm?b=2368754&u=3121769&m=100007&urllink=&afftrack=

Check out PCKL’s paddle lineup: PCKL IS OFFERING A DISCOUNT TO YOU, THE VIEWERS OF SLEEVE’S SPR… USE CODE PBREPORT15 FOR 15% OFF! HTTPS://SDQK.ME/EFKFEIAN/2KWQYP23

Learn about the R.A.W. (Reign and Win) Excluder 1, a fantastic paddle that supports non-profit bee farmers and contributes to preserving bees. Use the promo code “Reign10” to get a 10% discount on your purchase. Let’s work together to save the bees, who play a vital role in sustaining life on our planet. Click the link below to find out more about this product.

SPR Shirts and merch: https://stm-store.online/spr-merchand…

Just Paddles https://www.justpaddles.com/?rfsn=660…

#pickleball

#seniorpickleball

#pickleballislife

Social Links:

SPR on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?…

SPR on WEB https://stmdailynews.com/sleeves-seni…

SPR on Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/seniorpickl…

SPR on TikTok

twitter: https://twitter.com/SeniorPBReport

Space and Tech

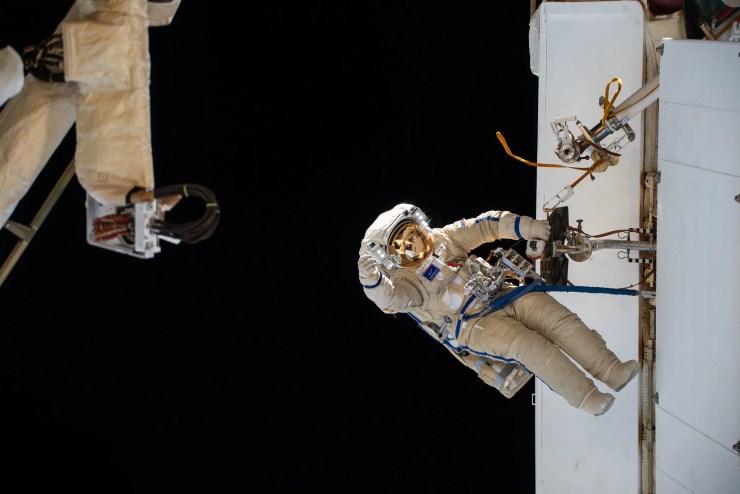

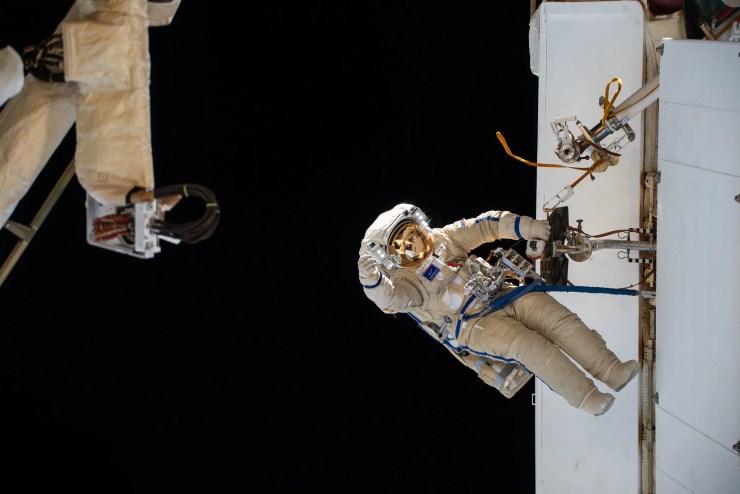

Exciting News: NASA Live Coverage of Roscosmos Cosmonauts on a Spacewalk!

Don’t miss NASA’s live coverage of Roscosmos cosmonauts on a spacewalk outside the International Space Station! #SpaceExploration

Get ready to witness a truly incredible event – a spacewalk outside the International Space Station conducted by two Roscosmos cosmonauts! NASA will be providing live coverage of this historic moment on Thursday, April 25, starting at 10:30 a.m. EDT. You definitely don’t want to miss this!

The spacewalk, expected to begin at 10:55 a.m. EDT, could last up to an impressive seven hours. So make sure to clear your schedule and prepare yourself for some out-of-this-world action!

But don’t worry if you can’t be near a TV, because NASA has got you covered. They will be streaming the spacewalk on various platforms including NASA+, NASA Television, the NASA app, YouTube, and their very own website. How convenient is that?

If you’re wondering how to catch this incredible event, fret not! NASA has made it super easy for everyone to enjoy the live coverage. You can stream NASA TV through numerous platforms, including social media. Just follow the instructions provided and you’ll be all set to witness history!

During this captivating spacewalk, Expedition 71 crewmates Oleg Kononenko and Nikolai Chub will embark on their mission. Their primary objective is to complete the deployment of a panel on a synthetic radar system located on the Nauka module. They will also be installing equipment and experiments on the Poisk module, which will be used to analyze the level of corrosion on various surfaces and modules of the space station. Science at its finest!

This noteworthy spacewalk will mark the 270th in support of the International Space Station. For Kononenko, this will be his seventh spacewalk, and he will be wearing the distinguished Orlan spacesuit with the red stripes. Chub, on the other hand, will be going on his second spacewalk and will be wearing the awe-inspiring spacesuit with the blue stripes. Talk about a fashionable space adventure!

So grab your popcorn, gather your friends and family, and get ready for an exhilarating experience. This upcoming spacewalk promises to be an event that will leave you in awe of the immense accomplishments and ongoing science conducted aboard the International Space Station.

Remember, you can catch all the action on NASA+, NASA Television, the NASA app, YouTube, and their website. Don’t miss out on this thrilling live coverage. Be a part of history and witness the wonders of space exploration firsthand. See you there!

Get breaking news, images, and features from the space station on the station blog, Instagram, Facebook, and X.

Learn more about International Space Station research and operations at:

Foodie News

Limited-Time Offer: Dive into Fallout’s World with Grubhub’s Nuka-Blast Burger!

“Grubhub debuts the Nuka-Blast Burger Meal to celebrate the series premiere of Fallout on Prime Video. Spice up your meal and join the Fallout universe!”

Calling all Fallout fans! Get ready to immerse yourself in the post-apocalyptic universe like never before. Grubhub is delighted to announce the launch of the limited-edition Nuka-Blast Burger Meal to coincide with the highly-anticipated series premiere of Fallout on Prime Video. This exclusive dining experience offers a unique blend of spice and flavor, allowing fans to indulge in the Fallout atmosphere while enjoying a delicious meal. Read on to discover all the exciting details!

The Nuka-Blast Burger Meal:

Prepare your taste buds for an explosive burst of flavor with the Nuka-Blast Burger Meal. This special package includes the Nuka-Blast Burger, a side of fries, and the iconic Nuka-Cola Victory SPECIAL RELEASE from Jones Soda. Designed to pay homage to the Nuka-World theme park before the Great War, Grubhub has crafted a meal that captures the essence of the Fallout universe.

The Nuka-Blast Burger itself is a mouth-watering creation filled with zest and heat. Featuring Calabrian chilis, fire-roasted jalapeño peppers, cayenne spices, and a specially crafted spicy dipping sauce made with ghost chili peppers, this burger guarantees to bring the heat. Accompanied by a serving of perfectly cooked fries, this meal balances the spice with a classic favorite. Wash it all down with the refreshing Nuka-Cola Victory SPECIAL RELEASE peach mango soda, the ultimate thirst-quencher for any Fallout fanatic.

“Tune In & Takeout” Series:

The Nuka-Blast Burger Meal is an integral part of Prime Video and Grubhub’s ongoing “Tune In & Takeout” series. This collaboration enhances your viewing experience by offering food pairings and promos that perfectly complement your favorite shows and movies on Prime Video. Over the years, Grubhub has delivered exclusive experiences for its subscribers, including popular titles such as The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel, The Summer I Turned Pretty, Candy Cane Lane, and Shotgun Wedding. Now, they’re bringing the Fallout universe to the table, giving fans an extraordinary way to engage with their favorite series.

Ordering Details:

To get your hands on the Nuka-Blast Burger Meal, simply place your order through Grubhub. Priced at $12 (before taxes, tips, and fees), this exclusive meal will be available for delivery on April 11 until supplies last. Please note that orders are limited to select areas in New York City and Los Angeles, and there is a limit of one meal per customer. Don’t miss out on this unforgettable dining experience!

Grubhub+ Trial Membership:

Prime members in the U.S. can enjoy additional benefits and rewards by signing up for a Grubhub+ trial membership, free for one year, through amazon.com/grubhub. In addition to $0 delivery fees on eligible orders, Grubhub+ members gain access to member-only perks and rewards from thousands of participating restaurants nationwide. Upgrade your dining experience and take advantage of this exciting opportunity.

Full terms and conditions can be found here.

Prime members in the U.S. enjoy savings, convenience and entertainment, all in one single membership. Members in the U.S. can sign up for a Grubhub+ trial membership, free for one year, by visiting amazon.com/grubhub. In addition to $0 delivery fees on eligible orders, Grubhub+ members get access to member-only perks and rewards from thousands of participating restaurants across the country, additional fees apply. For more Grubhub+ details and terms see here.

Grubhub’s partnership with Prime Video has resulted in another extraordinary dining experience with the Nuka-Blast Burger Meal. Celebrate the series premiere of Fallout and transport yourself to the post-apocalyptic world while savoring an incredible meal. The limited-edition Nuka-Blast Burger Meal offers fans a chance to embark on a culinary journey in a way that only Grubhub and Prime Video can deliver. Don’t miss your opportunity to be a part of this explosive adventure!

https://stmdailynews.com/category/food-and-beverage/

About Grubhub

Grubhub is part of Just Eat Takeaway.com (LSE: JET, AMS: TKWY), and is a leading U.S. food ordering and delivery marketplace. Dedicated to connecting diners with the food they love from their favorite local restaurants, Grubhub elevates food ordering through innovative restaurant technology, easy-to-use platforms and an improved delivery experience. Grubhub features more than 365,000 restaurant partners in over 4,000 U.S. cities.

About Fallout

Based on one of the greatest video game series of all time from acclaimed developer Bethesda Game Studios, Fallout is the story of haves and have-nots in a world in which there’s almost nothing left to have. Two hundred years after the apocalypse, the gentle denizens of luxury fallout shelters are forced to return to the irradiated hellscape their ancestors left behind—and are shocked to discover an incredibly complex, gleefully weird, and highly violent universe waiting for them. The series comes from Kilter Films and executive producers Jonathan Nolan and Lisa Joy. Nolan directed the first three episodes. Geneva Robertson-Dworet and Graham Wagner serve as executive producers, writers and co-showrunners. The series stars Ella Purnell, Aaron Moten, and Walton Goggins. Fallout will be available in more than 240 countries and territories around the world.

About Prime Video

Prime Video is a one-stop entertainment destination offering customers a vast collection of premium programming in one application available across thousands of devices. On Prime Video, customers can find their favorite movies, series, documentaries, and live sports – including Amazon MGM Studios-produced series and movies Saltburn, The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power, Reacher, The Boys, and AIR; licensed fan favorites Dawson’s Creek and M3GAN; Prime member exclusive Thursday Night Football; and programming from partners such as Max, Crunchyroll and MGM+ via Prime Video Channels add-on subscriptions, as well as more than 450 free ad-supported (FAST) Channels. Prime members in the U.S. can share a variety of benefits, including Prime Video, by using Amazon Household. Prime Video is one benefit among many that provides savings, convenience, and entertainment as part of the Prime membership. All customers, regardless of whether they have a Prime membership or not, can rent or buy titles, including blockbusters such as Barbie and Oppenheimer, via the Prime Video Store, and can enjoy content such as Jury Duty and Bosch: Legacy free with ads on Freevee. Customers can also go behind the scenes of their favorite movies and series with exclusive X-Ray access.

For more info visit www.amazon.com/primevideo.

SOURCE Grubhub

-

Community1 year ago

Community1 year agoDiana Gregory Talks to us about Diana Gregory’s Outreach Services

-

Senior Pickleball Report1 year ago

Senior Pickleball Report1 year agoACE PICKLEBALL CLUB TO DEBUT THEIR HIGHLY ANTICIPATED INDOOR PICKLEBALL FRANCHISES IN THE US, IN EARLY 2023

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year agoThe Absolute Most Comfortable Pickleball Shoe I’ve Ever Worn!

-

Automotive1 year ago

Automotive1 year ago2023 Nissan Sentra pricing starts at $19,950

-

Blog1 year ago

Blog1 year agoUnique Experiences at the CitizenM

-

Senior Pickleball Report1 year ago

Senior Pickleball Report1 year ago“THE PEOPLE’S CHOICE AWARDS OF PICKLEBALL” – VOTING OPEN

-

Blog1 year ago

Blog1 year agoAssistory Showing Support on Senior Assist Day

-

influencers1 year ago

influencers1 year agoKeeping Pickleball WEIRD, INEXPENSIVE and FUN? These GUYS are!