opinion

The rise of the autistic detective – why neurodivergent minds are at the heart of modern mysteries

The rise of the autistic detective – why neurodivergent minds are at the heart of modern mysteries

Dive into “The Knowledge,” where curiosity meets clarity. This playlist, in collaboration with STMDailyNews.com, is designed for viewers who value historical accuracy and insightful learning. Our short videos, ranging from 30 seconds to a minute and a half, make complex subjects easy to grasp in no time. Covering everything from historical events to contemporary processes and entertainment, “The Knowledge” bridges the past with the present. In a world where information is abundant yet often misused, our series aims to guide you through the noise, preserving vital knowledge and truths that shape our lives today. Perfect for curious minds eager to discover the ‘why’ and ‘how’ of everything around us. Subscribe and join in as we explore the facts that matter. https://stmdailynews.com/the-knowledge/

Discover more from Daily News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

unknown

Fact Check: Did Mike Rogers Admit the Travis Walton UFO Case Was a Hoax?

A fact check of viral claims that Mike Rogers admitted the Travis Walton UFO case was a hoax. We examine the evidence, the spotlight theory, and what the record actually shows.

Last Updated on February 6, 2026 by Daily News Staff

In recent years, viral YouTube videos and podcast commentary have revived claims that the 1975 Travis Walton UFO abduction case was an admitted hoax. One of the most widely repeated allegations asserts that Mike Rogers, the logging crew’s foreman, supposedly confessed that he and Walton staged the entire event using a spotlight from a ranger tower to fool their coworkers.

So, is there any truth to this claim?

After reviewing decades of interviews, skeptical investigations, and public records, the answer is clear:

There is no verified evidence that Mike Rogers ever admitted the Travis Walton incident was a hoax.

Where the Viral Claim Comes From

The “confession” story has circulated for years in online forums and was recently amplified by commentary-style YouTube and podcast content, including popular personality-driven shows. These versions often claim:

Rogers and Walton planned the incident in advance

A spotlight from a ranger or observation tower simulated the UFO

The rest of the crew was unaware of the hoax

Rogers later “admitted” this publicly

However, none of these claims are supported by primary documentation.

What the Documented Record Shows

No Recorded Confession Exists

There is no audio, video, affidavit, court record, or signed statement in which Mike Rogers admits staging the incident.

Rogers has repeatedly denied hoax allegations in interviews spanning decades.

Even prominent skeptical organizations do not cite any confession by Rogers.

If such an admission existed, it would be widely referenced in skeptical literature and would have effectively closed the case. It has not.

The “Ranger Tower Spotlight” Theory Lacks Evidence

No confirmed ranger tower or spotlight installation matching the claim has been documented at the location.

No ranger, third party, or equipment operator has ever come forward.

No physical evidence or corroborating testimony supports this explanation.

Even professional skeptics typically label this idea as speculative, not factual.

Why Skepticism Still Exists (Legitimately)

While the viral claim lacks evidence, skepticism about the Walton case is not unfounded. Common, well-documented critiques include:

Financial pressure tied to a logging contract

The limitations and inconsistency of polygraph testing

Walton’s later use of hypnosis, which is controversial in memory recall

Possible cultural influence from 1970s UFO media

Importantly, none of these critiques rely on a confession by Mike Rogers, because none exists.

Updates & Current Status of the Case

As of today:

No new witnesses have come forward to confirm a hoax

No participant has recanted their core testimony

No physical evidence has conclusively proven or disproven the event

Walton and Rogers have both continued to deny hoax allegations

The case remains unresolved, not debunked.

Why Viral Misinformation Persists

Online commentary formats often compress nuance into dramatic statements. Over time:

Speculation becomes repeated as “fact”

Hypothetical explanations are presented as admissions

Entertainment content is mistaken for investigative reporting

This is especially common with long-standing mysteries like the Walton case, where ambiguity invites exaggeration.

Viral Claims vs. Verified Facts

Viral Claim:

Mike Rogers admitted he and Travis Walton staged the UFO incident.

Verified Fact:

No documented confession exists. Rogers has consistently denied hoax claims.

Viral Claim:

A ranger tower spotlight was used to fake the UFO.

Verified Fact:

No evidence confirms a tower, spotlight, or third-party involvement.

Viral Claim:

The case was “officially debunked.”

Verified Fact:

No authoritative body has conclusively debunked or confirmed the incident.

Viral Claim:

All skeptics agree it was a hoax.

Verified Fact:

Even skeptical researchers acknowledge the absence of definitive proof.

Viral Claim:

Hollywood exposed the truth in Fire in the Sky.

Verified Fact:

The film significantly fictionalized Walton’s testimony for dramatic effect.

Bottom Line

❌ There is no verified admission by Mike Rogers

❌ There is no evidence of a ranger tower spotlight hoax

✅ There are legitimate unanswered questions about the case

✅ The incident remains debated, not solved

The Travis Walton story persists not because it has been proven — but because it has never been conclusively explained.

Related External Reading

- Travis Walton UFO Incident – Wikipedia

- Travis Walton Interviews – Coast to Coast AM

- Fire in the Sky (1993) – IMDb

- MUFON – Mutual UFO Network Case Files

- NICAP – National Investigations Committee on Aerial Phenomena

- Skeptical Inquirer – Scientific Analysis of Paranormal Claims

- U.S. National Archives – UFO & Government Records

Dive into “The Knowledge,” where curiosity meets clarity. This playlist, in collaboration with STMDailyNews.com, is designed for viewers who value historical accuracy and insightful learning. Our short videos, ranging from 30 seconds to a minute and a half, make complex subjects easy to grasp in no time. Covering everything from historical events to contemporary processes and entertainment, “The Knowledge” bridges the past with the present. In a world where information is abundant yet often misused, our series aims to guide you through the noise, preserving vital knowledge and truths that shape our lives today. Perfect for curious minds eager to discover the ‘why’ and ‘how’ of everything around us. Subscribe and join in as we explore the facts that matter. https://stmdailynews.com/the-knowledge/

Discover more from Daily News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Blog

The Empty Promise: Lynwood’s Lost Downtown Dream

In the 1970s, Lynwood, CA, dreamed of a downtown mall anchored by Montgomery Ward. Decades later, the empty lots told a story of ambition, delay, and renewal.

Artistic Image: R Washington and AI

In the early 1970s, Lynwood, California, dreamed big.

City leaders envisioned a new, modern downtown — a sprawling shopping and auto mall that would bring jobs, shoppers, and a sense of pride back to this small but growing city in the southeast corner of Los Angeles County. At the heart of the plan stood a gleaming new Montgomery Ward department store, which opened around 1973 and promised to anchor a larger commercial center that never fully came.

But for those of us who grew up in Lynwood during that time, the promise never quite materialized.

Instead, we remember acres of empty lots, chain-link fences, and faded “Coming Soon” signs that sat for decades — silent witnesses to a dream deferred.

The Vision That Stalled

In 1973, Lynwood’s Redevelopment Agency launched what it called Project Area A — an ambitious plan to clear and rebuild much of the city’s downtown core. Small businesses and homes were bought out, land was assembled, and the city floated bonds to support new construction.

For a brief moment, it looked as if the plan might work. Montgomery Ward opened its doors, serving as a retail beacon for the area. Yet the rest of the mall — the shops, restaurants, and auto dealerships — never came.

By the mid-1970s, much of downtown had been bulldozed, but little replaced it. And by the time Ward closed its Lynwood location in 1986, the vast lots surrounding it had become symbols of frustration and unfulfilled potential.

What Happened?

Some longtime residents whispered about corruption or backroom deals — the kind of speculation that grows when visible progress stalls.

But newspaper archives and redevelopment records tell a more complex story.

Lynwood’s plans collided with a series of hard realities:

The construction of the Century Freeway (I-105) disrupted neighborhoods and depressed land values. Environmental cleanup and ownership disputes slowed development. Economic shifts in retail — as malls in nearby Downey, South Gate, and Paramount attracted anchor stores — drained the local market. And later, political infighting among city officials made sustained redevelopment almost impossible.

To this day, there’s no public record of proven corruption directly tied to the 1970s mall plan. What did exist was a tangle of bureaucracy, economic change, and missed opportunity — a perfect storm that left Lynwood’s heart half-built and half-forgotten.

Growing Up Among the Vacant Lots

For those of us who were kids in Lynwood during that era, the story is more personal.

We remember the sight of the Montgomery Ward building — modern and hopeful at first, then shuttered and fading by the mid-1980s.

We remember riding bikes past the empty dirt fields that were supposed to become shopping plazas. And we remember the quiet frustration of adults who had believed the city’s promises.

Those empty blocks became our playgrounds — but they also became symbols of the gap between what Lynwood was and what it wanted to be.

A New Chapter: Plaza México and Beyond

By the late 1990s and early 2000s, the dream finally resurfaced in a new form.

Developers transformed the long-idle site into Plaza México, a vibrant commercial and cultural hub that celebrates Mexican and Latin American heritage.

It took nearly 30 years for Lynwood’s downtown to come alive again.

The result is beautiful — but it’s also bittersweet for those who remember how long the land sat empty, and how many local businesses and residents were displaced in pursuit of a dream that took a generation to fulfill.

Looking Back

The story of Lynwood’s lost mall isn’t just about urban planning.

It’s about hope, change, and resilience. It’s about how a community tried to reinvent itself — and how the children who grew up watching that effort still carry its memory.

Sometimes, when I drive through that stretch of Imperial Highway and Long Beach Boulevard, I still imagine what might have been: the bustling mall that never was, and the voices of a neighborhood caught between ambition and uncertainty.

📚 Further Reading

Montgomery Ward will close its Lynwood store. (Jan 3 1986) — Los Angeles Times.

Montgomery Ward Won’t Confirm Deal: Lynwood Council Says Retailer to Stay Open. (Jan 16 1986) — Los Angeles Times.

“Las Plazas of South LA” — academic paper by J.N. Leal (2012), discussing retail and redevelopment challenges in the region including Lynwood.

Proposed Lynwood Development Draws Support and Criticism. (2007) — Los Angeles Sentinel.

Wikipedia page: Lynwood, California — overview of the city including mention of Plaza México redevelopment.

Dive into “The Knowledge,” where curiosity meets clarity. This playlist, in collaboration with STMDailyNews.com, is designed for viewers who value historical accuracy and insightful learning. Our short videos, ranging from 30 seconds to a minute and a half, make complex subjects easy to grasp in no time. Covering everything from historical events to contemporary processes and entertainment, “The Knowledge” bridges the past with the present. In a world where information is abundant yet often misused, our series aims to guide you through the noise, preserving vital knowledge and truths that shape our lives today. Perfect for curious minds eager to discover the ‘why’ and ‘how’ of everything around us. Subscribe and join in as we explore the facts that matter. https://stmdailynews.com/the-knowledge/

Discover more from Daily News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Entertainment

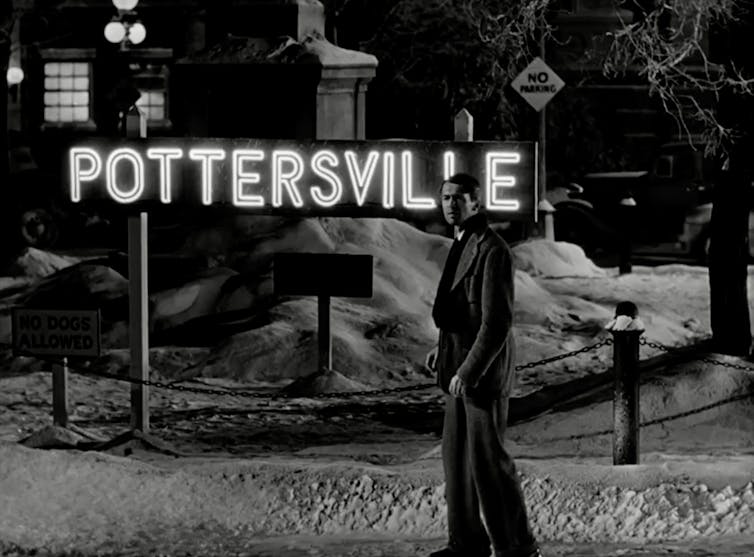

The dystopian Pottersville in ‘It’s a Wonderful Life’ is starting to feel less like fiction

A fresh look at It’s a Wonderful Life through the film’s darkest detour—Pottersville—and why its greed, corruption, and desensitization to cruelty feels uncomfortably familiar in America today.

Last Updated on March 8, 2026 by Daily News Staff

The dystopian Pottersville in ‘It’s a Wonderful Life’ is starting to feel less like fiction

Nora Gilbert, University of North Texas Along with millions of others, I’ll soon be taking 2 hours and 10 minutes out of my busy holiday schedule to sit down and watch a movie I’ve seen countless times before: Frank Capra’s “It’s a Wonderful Life,” which tells the story of a man’s existential crisis one Christmas Eve in the fictional town of Bedford Falls. There are lots of reasons why this eight-decade-old film still resonates, from its nostalgic pleasures to its cultural critiques. But when I watch it this year, the sequence where Bedford Falls transforms into the dark and dystopian “Pottersville” will resonate the most. In the film, protagonist George Bailey, who’s played by Jimmy Stewart, is on the brink of suicide. He seems to have achieved the hallmarks of the American dream: He’s taken over his father’s loan business, married the love of his life and fathered four excessively adorable children. But George feels stifled and beaten down. His Uncle Billy has misplaced US$8,000 of the company’s money, and the town’s resident tyrant, Mr. Potter, is using the mishap to try to ruin George, who’s his last remaining business competitor. An angel named Clarence is tasked with pulling George back from the brink. To stop him from attempting suicide, Clarence decides to show George what life would have been like if he’d never been born. In this alternate reality, Bedford Falls is called Pottersville, a place Mr. Potter runs as a ruthless banker and slumlord.

Frank Capra, anti-fascist

In 1946, Capra was just returning to Hollywood filmmaking after serving for four years in the U.S. Army, where the Office of War Information had tasked him with producing a series of documentary films about World War II and the lead-up to it. Even though Capra hadn’t been on the front lines, he’d been immersed in the sounds and images of war for years on end, and he had become acutely familiar with Germany, Italy and Japan’s respective rises to fascism. When deciding on his first postwar film, Capra recalled in his autobiography that he specifically “knew one thing – it would not be about war.” Instead, he chose to adapt a short story by Philip Van Doren Stern, “The Greatest Gift,” that Stern had originally sent to friends and family as a Christmas card in 1943. Stern’s story is certainly not about war. But it’s not exactly about Christmas, either. As Stern writes in his opening lines:“The little town straggling up the hill was bright with colored Christmas lights. But George Pratt did not see them. He was leaning over the railing of the iron bridge, staring down moodily at the black water.”The protagonist contemplates suicide because he’s “sick of everything” in the small-town “mudhole” he’s stuck in – until, that is, a “strange little man” gives him the chance to see what life would be like if he’d never been born. It was Capra and his team of screenwriters who added the sinister Henry F. Potter to Stern’s short, simple tale. The Potter subplot encapsulates the film’s most trenchant, still-resonant themes: the unfairness of socioeconomic injustices; the pervasiveness of corporate and political corruption; the threat of monopolized power; the need for affordable housing. These themes had, of course, run through many of Capra’s prewar films as well: “Mr. Deeds Goes to Town,” “You Can’t Take It with You,” “Meet John Doe” and “Mr. Smith Goes to Washington,” the last of which also starred Jimmy Stewart. But they take on a different kind of weight in “It’s a Wonderful Life” – a weight that’s especially visible on the weathered face of Stewart, who himself had just returned from a harrowing four-year tour of duty as a bomber pilot in Europe. The idealistic vigor with which Stewart had fought crooked politicians and oligarchs as Mr. Smith is replaced by the bitterness, exhaustion, frustration and desperation with which he battles against Mr. Potter as George Bailey.

Life after Pottersville

By the time George has begged and pleaded his way out of Pottersville, the lost $8,000 is no longer top of mind. He’s mainly just relieved to find Bedford Falls as he had left it, warts and all. And yet, the Bedford Falls that George returns to isn’t quite the same as the one he left behind. In this Bedford Falls, the community rallies together to figure out a way to recoup George’s missing money. Their pre-digital version of a GoFundMe page saves George from what he’d feared most: bankruptcy, scandal and prison. And even though his wife, Mary, tries to attribute this sudden wave of collectivist, activist energy to some sort of divine intervention – “George, it’s a miracle; it’s a miracle!” – Uncle Billy points out that it really came about through more earthly organizing means: “Mary did it, George; Mary did it! She told some people you were in trouble, and they scattered all over town collecting money!”

Discover more from Daily News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.