The Bridge

Federal judge rules that Louisiana shalt not require public schools to post the Ten Commandments

Charles J. Russo, University of Dayton

Do the Ten Commandments have a valid place in U.S. classrooms? Louisiana’s Legislature and governor insist the answer is “yes.” But on Nov. 12, 2024, a federal judge said “no.”

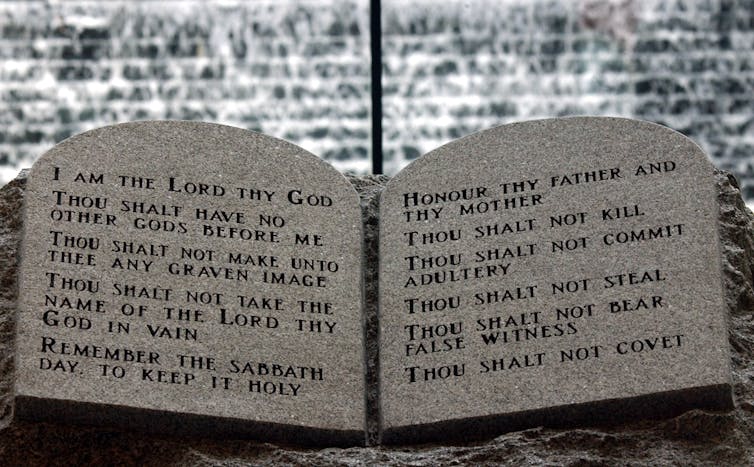

U.S. District Judge John W. deGravelles blocked the state’s controversial House Bill 71, which Gov. Jeff Landry had signed into law on June 19, 2024. The measure would have required all schools that receive public funding to post a specific version of the commandments, similar to the King James translation of the Bible used in many, but not all, Protestant churches. It is not the same version used by Catholics or Jews.

Officials were also supposed to post a context statement highlighting the role of the Ten Commandments in American history and could display the Pilgrims’ Mayflower Compact, the Declaration of Independence and the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, a federal enactment to settle the frontier – and the earliest congressional document encouraging the creation of schools.

The law’s defenders argued that its purpose was not only religious, but historical. Judge deGravelles, though, firmly rejected that argument, striking down HB 71 as “unconstitutional on its face and in all applications.” The law had an “overtly religious” purpose, he wrote, in violation of the First Amendment, according to which “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.”

Regardless of the Ten Commandments’ impact on civil law, there was a clear religious intent behind Louisiana’s law. During debate over its passage, for example, the bill’s author, state Rep. Dodie Horton said, “I’m not concerned with an atheist. I’m not concerned with a Muslim. I’m concerned with our children looking and seeing what God’s law is.”

Louisiana Attorney General Liz Murrill has said she intends to appeal the judge’s ruling.

As someone who teaches and researches law around religion and education, with an eye toward defending religious freedom, I believe this is an important test case at a time when the Supreme Court’s thinking on religion and public education is becoming more religion-friendly – perhaps the most it has ever been.

How SCOTUS has ruled before

Litigation over the Ten Commandments is not new. More than 40 years ago, in Stone v. Graham, the Supreme Court rejected a Kentucky statute that mandated displays of the Ten Commandments in classrooms.

The court reasoned that the underlying law violated the First Amendment’s establishment clause – “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion” – because the mandate lacked a secular purpose.

The justices were not persuaded by a small notation on posters that described the Ten Commandments as the “fundamental legal code of Western Civilization and the Common Law of the United States.”

Twenty-five years later, the Supreme Court again took up cases challenging public displays of the Ten Commandments, although not in schools. This time, the justices reached mixed results.

The first arose in Kentucky where officials had erected a county courthouse display of texts including the Ten Commandments, the Magna Carta, the Declaration of Independence and a biblical citation. In a 2005 ruling in McCreary County, Kentucky v. American Civil Liberties Union of Kentucky the five-member majority agreed that the display of the Ten Commandments violated the establishment clause, largely because it lacked a secular legislative purpose.

On the same day, though, the Supreme Court reached the opposite result in Van Orden v. Perry, a case from Texas. The court upheld the constitutionality of a display of the Ten Commandments on the grounds of the state capitol as one of 17 monuments and 21 historical markers commemorating Texas’ history.

Unlike the fairly new display in Kentucky, the one in Texas, which had existed since the early 1960s, was erected using private funds. The court permitted the Ten Commandments to remain because, despite their religious significance, the Texas monument was a more passive display, not posted on the courthouse door.

Louisiana’s law

Louisiana’s law would have required public school officials to display framed copies of the Ten Commandments in all public school classrooms. Posters were supposed to be at least 11-by-14 inches and printed with a large, easily readable font. The legislation would have allowed, but did not require, officials to use state funds to purchase these posters. Displays could also be received as donations or purchased with gifted funds.

The bill’s author, Horton, previously sponsored Louisiana’s law mandating that “In God We Trust” be posted in public school classrooms.

In defending the Ten Commandments proposal, Horton said it honors the country’s origins.

“The Ten Commandments are the basis of all laws in Louisiana,” she told fellow lawmakers, “and given all the junk our children are exposed to in classrooms today, it’s imperative that we put the Ten Commandments back in a prominent position.”

Justifying the bill, Horton pointed to Kennedy v. Bremerton School District, a 2022 Supreme Court decision. Here, the justices held that educational officials could not prevent a football coach from praying on the field at the end of games because he engaged in personal religious observance protected by the First Amendment.

“The landscape has changed,” she said.

New frontier

Indeed it has.

For decades, the Supreme Court used a three-part measure called the Lemon v. Kurtzman test to assess whether a government action violated the establishment clause. Under this test, when a government action or policy intersects with religion, it had to meet three criteria. A policy had to have a secular legislative purpose; its principal or primary effect could neither advance nor inhibit religion; and it could not result in excessive entanglement between state and religious officials.

Another test the Supreme Court sometimes applied, stemming from Lynch v. Donnelly in 1984, invalidated governmental actions appearing to endorse religion.

The majority of the current court, though, abandoned both the Lemon and endorsement tests in Kennedy v. Bremerton. Writing for the court, Justice Neil Gorsuch ruled that “the Establishment Clause must be interpreted by ‘reference to historical practices and understandings.’” He added that the court “long ago abandoned Lemon and its endorsement test offshoot.”

What that new historical practices and understandings standard means remains to be seen.

More than 80 years ago, in West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette the Supreme Court decided in a 6-3 opinion that students cannot be compelled to salute the American flag, which includes reciting the words “under God” in the Pledge of Allegiance, if doing so goes against their religious beliefs. While H.B. 71 does not require students to recite the Ten Commandments, they would be constantly exposed to its presence in their classrooms, reducing them to what the judge described as a “captive audience” – violating their parents’ rights to the free exercise of religion.

In 1962’s Engel v. Vitale, the Supreme Court’s first case on prayer in public schools, the majority observed that “the Founders of our Constitution [recognized] that religion is too personal, too sacred, too holy,” to permit civil authorities to impose particular beliefs. I see no reason to abandon that view.

This is an updated version of an article originally published on June 4, 2024.

Charles J. Russo, Joseph Panzer Chair in Education and Research Professor of Law, University of Dayton

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

STM Daily News is a vibrant news blog dedicated to sharing the brighter side of human experiences. Emphasizing positive, uplifting stories, the site delivers inspiring, informative, and well-researched content. With a commitment to accurate, fair, and responsible journalism, STM Daily News aims to foster a community of readers passionate about positive change and engaged in meaningful conversations. Join the movement and explore stories that celebrate the positive impacts shaping our world.

Discover more from Daily News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Urbanism

The Building That Proved Los Angeles Could Go Vertical

Los Angeles once banned skyscrapers, yet City Hall broke the height limit and proved high-rise buildings could be engineered safely in an earthquake zone.

Last Updated on February 19, 2026 by Daily News Staff

How City Hall Quietly Undermined LA’s Own Height Limits

The Knowledge Series | STM Daily News

For more than half a century, Los Angeles enforced one of the strictest building height limits in the United States. Beginning in 1905, most buildings were capped at 150 feet, shaping a city that grew outward rather than upward.

The goal was clear: avoid the congestion, shadows, and fire dangers associated with dense Eastern cities. Los Angeles sold itself as open, sunlit, and horizontal — a place where growth spread across land, not into the sky.

And yet, in 1928, Los Angeles City Hall rose to 454 feet, towering over the city like a contradiction in concrete.

It wasn’t built to spark a commercial skyscraper boom.

But it ended up proving that Los Angeles could safely build one.

A Rule Designed to Prevent a Manhattan-Style City

The original height restriction was rooted in early 20th-century fears:

- Limited firefighting capabilities

- Concerns over blocked sunlight and airflow

- Anxiety about congestion and overcrowding

- A strong desire not to resemble New York or Chicago

Los Angeles wanted prosperity — just not vertical density.

The height cap reinforced a development model where:

- Office districts stayed low-rise

- Growth moved outward

- Automobiles became essential

- Downtown never consolidated into a dense core

This philosophy held firm even as other American cities raced upward.

Why City Hall Was Never Meant to Change the Rules

City Hall was intentionally exempt from the height limit because the law applied primarily to private commercial buildings, not civic monuments.

But city leaders were explicit about one thing:

City Hall was not a precedent.

It was designed to:

- Serve as a symbolic seat of government

- Stand alone as a civic landmark

- Represent stability, authority, and modern governance

- Avoid competing with private office buildings

In effect, Los Angeles wanted a skyline icon — without a skyline.

Innovation Hidden in Plain Sight

What made City Hall truly significant wasn’t just its height — it was how it was built.

At a time when seismic science was still developing, City Hall incorporated advanced structural ideas for its era:

- A steel-frame skeleton designed for flexibility

- Reinforced concrete shear walls for lateral strength

- A tapered tower to reduce wind and seismic stress

- Thick structural cores that distributed force instead of resisting it rigidly

These choices weren’t about aesthetics — they were about survival.

The Earthquake That Changed the Conversation

In 1933, the Long Beach earthquake struck Southern California, causing widespread damage and reshaping building codes statewide.

Los Angeles City Hall survived with minimal structural damage.

This moment quietly reshaped the debate:

- A tall building had endured a major earthquake

- Structural engineering had proven effective

- Height alone was no longer the enemy — poor design was

City Hall didn’t just survive — it validated a new approach to vertical construction in seismic regions.

Proof Without Permission

Despite this success, Los Angeles did not rush to repeal its height limits.

Cultural resistance to density remained strong, and developers continued to build outward rather than upward. But the technical argument had already been settled.

City Hall stood as living proof that:

- High-rise buildings could be engineered safely in Los Angeles

- Earthquakes were a challenge, not a barrier

- Fire, structural, and seismic risks could be managed

The height restriction was no longer about safety — it was about philosophy.

The Ironic Legacy

When Los Angeles finally lifted its height limit in 1957, the city did not suddenly erupt into skyscrapers. The habit of building outward was already deeply entrenched.

The result:

- A skyline that arrived decades late

- Uneven density across the region

- Multiple business centers instead of one core

- Housing and transit challenges baked into the city’s growth pattern

City Hall never triggered a skyscraper boom — but it quietly made one possible.

Why This Still Matters

Today, Los Angeles continues to wrestle with:

- Housing shortages

- Transit-oriented development debates

- Height and zoning battles near rail corridors

- Resistance to density in a growing city

These debates didn’t begin recently.

They trace back to a single contradiction: a city that banned tall buildings — while proving they could be built safely all along.

Los Angeles City Hall wasn’t just a monument.

It was a test case — and it passed.

Further Reading & Sources

- Los Angeles Department of City Planning – History of Urban Planning in LA

- Los Angeles Conservancy – History & Architecture of LA City Hall

- Water and Power Associates – Early Los Angeles Buildings & Height Limits

- USGS – How Buildings Are Designed to Withstand Earthquakes

- Los Angeles Department of Building and Safety – Building Code History

More from The Knowledge Series on STM Daily News

Discover more from Daily News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The Knowledge

How a 22-year-old George Washington learned how to lead, from a series of mistakes in the Pennsylvania wilderness

This Presidents Day, I’ve been thinking about George Washington − not at his finest hour, but possibly at his worst.

Christopher Magra, University of Tennessee

This Presidents Day, I’ve been thinking about George Washington − not at his finest hour, but possibly at his worst.

In 1754, a 22-year-old Washington marched into the wilderness surrounding Pittsburgh with more ambition than sense. He volunteered to travel to the Ohio Valley on a mission to deliver a letter from Robert Dinwiddie, governor of Virginia, to the commander of French troops in the Ohio territory. This military mission sparked an international war, cost him his first command and taught him lessons that would shape the American Revolution.

As a professor of early American history who has written two books on the American Revolution, I’ve learned that Washington’s time spent in the Fort Duquesne area taught him valuable lessons about frontier warfare, international diplomacy and personal resilience.

The mission to expel the French

In 1753, Dinwiddie decided to expel French fur trappers and military forces from the strategic confluence of three mighty waterways that crisscrossed the interior of the continent: the Allegheny, Monongahela and Ohio rivers. This confluence is where downtown Pittsburgh now stands, but at the time it was wilderness.

King George II authorized Dinwiddie to use force, if necessary, to secure lands that Virginia was claiming as its own.

As a major in the Virginia provincial militia, Washington wanted the assignment to deliver Dinwiddie’s demand that the French retreat. He believe the assignment would secure him a British army commission.

Washington received his marching orders on Oct. 31, 1753. He traveled to Fort Le Boeuf in northwestern Pennsylvania and returned a month later with a polite but firm “no” from the French.

Dinwiddie promoted Washington from major to lieutenant colonel and ordered him to return to the Ohio River Valley in April 1754 with 160 men. Washington quickly learned that French forces of about 500 men had already constructed the formidable Fort Duquesne at the forks of the Ohio. It was at this point that he faced his first major test as a military leader. Instead of falling back to gather more substantial reinforcements, he pushed forward. This decision reflected an aggressive, perhaps naive, brand of leadership characterized by a desire for action over caution.

Washington’s initial confidence was high. He famously wrote to his brother that there was “something charming” in the sound of whistling bullets.

The Jumonville affair and an international crisis

Perhaps the most controversial moment of Washington’s early leadership occurred on May 28, 1754, about 40 miles south of Fort Duquesne. Guided by the Seneca leader Tanacharison – known as the “Half King” – and 12 Seneca warriors, Washington and his detachment of 40 militiamen ambushed a party of 35 French Canadian militiamen led by Ensign Joseph Coulon de Jumonville. The Jumonville affair lasted only 15 minutes, but its repercussions were global.

Ten of the French, including Jumonville, were killed. Washington’s inability to control his Native American allies – the Seneca warriors executed Jumonville – exposed a critical gap in his early leadership. He lacked the ability to manage the volatile intercultural alliances necessary for frontier warfare.

Washington also allowed one enemy soldier to escape to warn Fort Duquesne. This skirmish effectively ignited the French and Indian War, and Washington found himself at the center of a burgeoning international crisis.

Defeat at Fort Necessity

Washington then made the fateful decision to dig in and call for reinforcements instead of retreating in the face of inevitable French retaliation. Reinforcements arrived: 200 Virginia militiamen and 100 British regulars. They brought news from Dinwiddie: congratulations on Washington’s victory and his promotion to colonel.

His inexperience showed in his design of Fort Necessity. He positioned the small, circular palisade in a meadow depression, where surrounding wooded high ground allowed enemy marksmen to fire down with impunity. Worse still, Tanacharison, disillusioned with Washington’s leadership and the British failure to follow through with promised support, had already departed with his warriors weeks earlier. When the French and their Native American allies finally attacked on July 3, heavy rains flooded the shallow trenches, soaking gunpowder and leaving Washington’s men vulnerable inside their poorly designed fortification.

The battle of Fort Necessity was a grueling, daylong engagement in the mud and rain. Approximately 700 French and Native American allies surrounded the combined force of 460 Virginian militiamen and British regulars. Despite being outnumbered and outmaneuvered, Washington maintained order among his demoralized troops. When French commander Louis Coulon de Villiers – Jumonville’s brother – offered a truce, Washington faced the most humbling moment of his young life: the necessity of surrender. His decision to capitulate was a pragmatic act of leadership that prioritized the survival of his men over personal honor.

The surrender also included a stinging lesson in the nuances of diplomacy. Because Washington could not read French, he signed a document that used the word “l’assassinat,” which translates to “assassination,” to describe Jumonville’s death. This inadvertent admission that he had ordered the assassination of a French diplomat became propaganda for the French, teaching Washington the vital importance of optics in international relations.

Lessons that forged a leader

The 1754 campaign ended in a full retreat to Virginia, and Washington resigned his commission shortly thereafter. Yet, this period was essential in transforming Washington from a man seeking personal glory into one who understood the weight of responsibility.

He learned that leadership required more than courage – it demanded understanding of terrain, cultural awareness of allies and enemies, and political acumen. The strategic importance of the Ohio River Valley, a gateway to the continental interior and vast fur-trading networks, made these lessons all the more significant.

Ultimately, the hard lessons Washington learned at the threshold of Fort Duquesne in 1754 provided the foundational experience for his later role as commander in chief of the Continental Army. The decisions he made in Pennsylvania and the Ohio wilderness, including the impulsive attack, the poor choice of defensive ground and the diplomatic oversight, were the very errors he would spend the rest of his military career correcting.

Though he did not capture Fort Duquesne in 1754, the young George Washington left the woods of Pennsylvania with a far more valuable prize: the tempered, resilient spirit of a leader who had learned from his mistakes.

Christopher Magra, Professor of American History, University of Tennessee

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Dive into “The Knowledge,” where curiosity meets clarity. This playlist, in collaboration with STMDailyNews.com, is designed for viewers who value historical accuracy and insightful learning. Our short videos, ranging from 30 seconds to a minute and a half, make complex subjects easy to grasp in no time. Covering everything from historical events to contemporary processes and entertainment, “The Knowledge” bridges the past with the present. In a world where information is abundant yet often misused, our series aims to guide you through the noise, preserving vital knowledge and truths that shape our lives today. Perfect for curious minds eager to discover the ‘why’ and ‘how’ of everything around us. Subscribe and join in as we explore the facts that matter. https://stmdailynews.com/the-knowledge/

Discover more from Daily News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Community

Local governments provide proof that polarization is not inevitable

Local politics help mitigate national polarization by focusing on concrete issues like infrastructure and community needs rather than divisive symbolic debates. A survey indicates that local officials experience less partisanship, as interpersonal connections foster recognition of shared interests. This suggests that reducing polarization is possible through collaboration and changes in election laws.

Lauren Hall, Rochester Institute of Technology

When it comes to national politics, Americans are fiercely divided across a range of issues, including gun control, election security and vaccines. It’s not new for Republicans and Democrats to be at odds over issues, but things have reached a point where even the idea of compromising appears to be anathema, making it more difficult to solve thorny problems.

But things are much less heated at the local level. A survey of more than 1,400 local officials by the Carnegie Corporation and CivicPulse found that local governments are “largely insulated from the harshest effects of polarization.” Communities with fewer than 50,000 residents proved especially resilient to partisan dysfunction.

Why this difference? As a political scientist, I believe that lessons from the local level not only open a window onto how polarization works but also the dynamics and tools that can help reduce it.

Problems are more concrete

Local governments deal with concrete issues – sometimes literally, when it comes to paving roads and fixing potholes. In general, cities and counties handle day-to-day functions, such as garbage pickup, running schools and enforcing zoning rules. Addressing tangible needs keeps local leaders’ attention fixed on specific problems that call out for specific solutions, not lengthy ideological debates.

By contrast, a lot of national political conflict in the U.S. involves symbolic issues, such as debates about identity and values on topics such as race, abortion and transgender rights. These battles are often divisive, even more so than purely ideological disagreements, because they can activate tribal differences and prove more resistant to compromise.

Such arguments at the national level, or on social media, can lead to wildly inaccurate stereotypes about people with opposing views. Today’s partisans often perceive their opponents as far more extreme than they actually are, or they may stereotype them – imagining that all Republicans are wealthy, evangelical culture warriors, for instance, or conversely being convinced that all Democrats are radical urban activists. In terms of ideology, the median members of both parties, in fact, look similar.

These kinds of misperceptions can fuel hostility.

Local officials, however, live among the human beings they represent, whose complexity defies caricature. Living and interacting in the same communities leads to greater recognition of shared interests and values, according to the Carnegie/CivicPulse survey.

Meaningful interaction with others, including partisans of the opposing party, reduces prejudice about them. Local government provides a natural space where identities overlap.

People are complicated

In national U.S. politics today, large groups of individuals are divided not only by party but a variety of other factors, including race, religion, geography and social networks. When these differences align with ideology, political disagreement can feel like an existential threat.

Such differences are not always as pronounced at the local level. A neighbor who disagrees about property taxes could be the coach of your child’s soccer team. Your fellow school board member might share your concerns about curriculum but vote differently in presidential elections.

These cross-cutting connections remind us that political opponents are not a monolithic enemy but complex individuals. When people discover they have commonalities outside of politics with others holding opposing views, polarization can decrease significantly.

Finally, most local elections are technically nonpartisan. Keeping party labels off ballots allows voters to judge candidates as individuals and not merely as Republicans or Democrats.

National implications

None of this means local politics are utopian.

Like water, polarization tends to run downhill, from the national level to local contests, particularly in major cities where candidates for mayor and other office are more likely to run as partisans. Local governments also see culture war debates, notably in the area of public school instruction.

Nevertheless, the relative partisan calm of local governance suggests that polarization is not inevitable. It emerges from specific conditions that can be altered.

Polarization might be reduced by creating more opportunities for cross-partisan collaboration around concrete problems. Philanthropists and even states might invest in local journalism that covers pragmatic governance rather than partisan conflict. More cities and counties could adopt changes in election law that would de-emphasize party labels where they add little information for voters.

Aside from structural changes, individual Americans can strive to recognize that their neighbors are not the cardboard cutouts they might imagine when thinking about “the other side.” Instead, Americans can recognize that even political opponents are navigating similar landscapes of community, personal challenges and time constraints, with often similar desires to see their roads paved and their children well educated.

The conditions shaping our interactions matter enormously. If conditions change, perhaps less partisan rancor will be the result.

Lauren Hall, Associate professor of Political Science, Rochester Institute of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The Bridge is a section of the STM Daily News Blog meant for diversity, offering real news stories about bona fide community efforts to perpetuate a greater good. The purpose of The Bridge is to connect the divides that separate us, fostering understanding and empathy among different groups. By highlighting positive initiatives and inspirational actions, The Bridge aims to create a sense of unity and shared purpose. This section brings to light stories of individuals and organizations working tirelessly to promote inclusivity, equality, and mutual respect. Through these narratives, readers are encouraged to appreciate the richness of diverse perspectives and to participate actively in building stronger, more cohesive communities.

https://stmdailynews.com/the-bridge

Discover more from Daily News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.