Child Health

National Poll: Some parents may not be making the most of well child visits

While many parents regularly take children to checkups, some may consider more proactive steps to make them as productive as possible.

How parents prepare for children’s checkups

« National Poll: Some parents may not be making the most of well child visits

Newswise — While most parents and caregivers stay on top of scheduling regular checkups for their kids, they may not always be making the most of them, a national poll suggests.

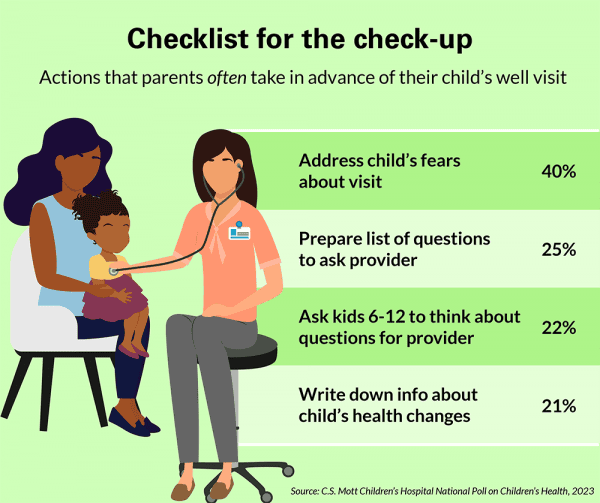

Most parents report their child has had a well visit in the past two years and two thirds say they always see the same provider, according to the C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital National Poll on Children’s Health at University of Michigan Health. However, fewer parents took all recommended steps to prepare themselves and their kids ahead of time.

“Regular well visits mean guaranteed face time with your child’s doctor and an opportunity to not only discuss specific concerns and questions about your child’s health but get their advice on general health topics like nutrition, sleep and behavior,” said Mott Poll co-director Sarah Clark, M.P.H. “We were pleased to see that the majority of parents regularly make these appointments and maintain relationships with a trusted provider. But they may not always be taking a proactive approach to ensuring they address all relevant health concerns impacting their child’s physical, emotional and behavioral health at every visit.”

In advance of well visits, a fourth of parents say they often prepare a list of questions to ask the provider, while a little over half said they sometimes wrote things down and about a fifth said they never do.

Meanwhile, about a fifth of parents say they often write down information about their child’s health changes while half say they sometimes take this step and three in 10 don’t do this at all.

“Well visits are busy, and in the moment, it’s easy for parents to forget to bring up questions or concerns with a doctor,” Clark said. “Writing them down ahead of time will help prioritize topics and help you get the most out of the appointment.”

Less than 15% of parents say they often research information online to discuss with the provider, while about half sometimes do and 38% never do.

“We are constantly learning new information that may impact children’s health and some recommendations may evolve or be updated,” Clark said. “Many pediatricians and care providers will bring these topics up themselves but not always. It’s always helpful for parents to do some homework ahead of time to make sure they’re aware of any timely topics affecting their child’s age group.”

Preparing children for the visit

Two in five parents say they often take steps to prepare their child for an upcoming well visit by addressing any fears they may have while slightly more than that sometimes do this while a little less than one in five never do this. A fourth of parents often also offer rewards for cooperating while less than half sometimes use such incentives.

For parents of children aged 6-12, a little more than one in five also regularly ask the child to think about questions for the provider.

“As kids approach puberty, their bodies begin changing. A well visit is a great opportunity to have the provider explain why these changes happen,” Clark said. “Having kids think about health topics themselves is also good practice for when they get older and parents become less involved with health visits. Preparing for this transition early will benefit them when they need to take more ownership of their health.”

Most parents also recall completing questionnaires and checklists about their child at well visits. Among these parents, the majority say they understand the purpose but just about three fourths say they receive feedback about how their child is doing.

“Children and their families are more often getting questionnaires at visits to help identify issues like sleep problems, challenges impacting emotional health and behavioral health concerns,” Clark said. “But when time is short, this may not come up during the actual visit. It’s important parents have conversations with providers about any issues that may surface from the child’s or family’s responses.”

Seeing providers familiar with your child’s history

Nearly half of parents say they schedule well visits with their child’s regular provider even if they have a long wait for an appointment. A third of parents also strongly agree their child is more likely to follow advice if it comes from a provider their child knows well.

For their child’s most recent well visit, more than half of parents also rate the provider as excellent for knowing the child’s health history, answering all their questions and giving recommendations that are realistic for the family.

A primary care physician familiar with a child and their specific health history will help them stay healthy, prevent disease and illness by identifying risk factors and taking the right steps to manage chronic disease care, Clark says.

“We know that continuity with the same provider has long term health benefits for children. Parents polled whose child always sees the same provider for well visits are also more likely to rate the provider as excellent,” Clark said. “Nurturing a relationship with a primary care provider means that the health professional who knows your child best is the one providing individualized care and helping your family navigate important decisions impacting their health.”

However, when well visits are scheduled with a different provider, either by choice or necessity, “parents may benefit from different explanations or perspectives on their child’s health,” Clark added.

The nationally representative report is based on responses from 1,331 parents with children aged 1 to 12 years who were polled in August-September 2022.

Five ways to ensure the most productive well child visit, according to Mott experts:

- Build a long-lasting trusted relationship with the same primary care provider who your child always sees for appointments, which may include a pediatrician, other family physician or nurse practitioner.

- Write down questions regarding your child’s physical, emotional and behavioral health in the same place as they come up to review again when a child is due for a well visit.

- Share input from teachers or daycare providers about the child’s behavior or school performance and ask the primary care provider for the need for further assessment or therapy.

- Prepare children for the visit. If there’s a physical exam, talk them through what to expect. For young children who need immunizations or blood draws, prepare them with books ahead of time, consider comfort positions and distractions like cartoons on screens during shots or give them something fun to look forward to after the visit like ice cream. Never promise them they won’t get a shot. More tips here.

- For older children, help them come up with a list of questions to ask the doctor themselves.

Source: Michigan Medicine – University of Michigan

Discover more from Daily News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Child Health

Recognizing the Signs of Pediatric Growth Hormone Deficiency: How Early Recognition and Advocacy Helped One Family Find Answers

Diane Benke noticed her son Alex’s height concerns starting at age 7, despite his pediatrician’s reassurances. After persistent worries, they consulted an endocrinologist, leading to a diagnosis of Pediatric Growth Hormone Deficiency (PGHD). Following treatment changes, including a switch to weekly hormone injections, Alex’s growth improved, allowing the family to focus on their well-being.

Last Updated on February 5, 2026 by Daily News Staff

(Family Features) “Our concerns about Alex’s growth began around the age of 7,” said his mother, Diane Benke.

Though Alex measured around the 50th percentile for weight, his height consistently hovered around the 20th percentile. Benke’s instincts told her something wasn’t quite right.

“I kept asking our pediatrician if this could mean something more,” she said. “Each time, I was reassured that everything was fine. After all, I’m only 5 feet tall myself.”

At first, Benke tried setting her worries aside. Alex was one of the youngest in his class, and she wondered if he could simply be a “late bloomer.”

However, as Alex progressed through elementary school, particularly in the 4th and 6th grades, his height percentile dropped into the single digits. The height difference between Alex and his peers became impossible to ignore.

Despite Benke’s growing concerns, their pediatrician continued to assure them Alex was fine.

“We were told as long as he was making some progress on the growth chart, there was no need to worry,” she said, “but we were never actually shown the charts.”

It wasn’t until one of Benke’s friends confided that her own daughter had recently been diagnosed with Pediatric Growth Hormone Deficiency (PGHD) that she decided to seek an endocrinologist.

“Although it took several months to get an appointment,” Benke said, “we were determined to get more answers.”

Navigating the Diagnosis Process

Getting a diagnosis for many medical conditions can be a long journey. However, early detection and diagnosis of PGHD is important. It can help minimize the impact on overall health and support optimal growth.

Once Alex was seen by a pediatric endocrinologist, he underwent a series of evaluations, including bloodwork, a bone age X-ray to compare his chronological age with his skeletal age and a growth hormone stimulation test, which measures the body’s ability to produce growth hormone. He also had a brain MRI to rule out the potential of any pituitary abnormalities.

The results of these tests confirmed the diagnosis of PGHD, a rare condition that occurs when the pituitary gland does not produce enough growth hormone. PGHD affects an estimated 1 in 4,000-10,000 children.

Some common signs parents might notice include: their child being significantly shorter than other kids their age, slower growth rate over time, delayed puberty, reduced muscle strength or lower energy levels, slower bone development and delayed physical milestones.

“Receiving Alex’s diagnosis was a relief,” Benke said. “It provided clarity and a path forward.”

Moving Forward with Treatment

“While the diagnosis process was exhausting, starting treatment made the process worthwhile,” Benke said.

For decades, daily injections of a drug called somatropin, which is similar to the growth hormone your body produces, have been the standard of care for PGHD. It wasn’t until 2015 that the Growth Hormone Research Society recognized the need for a long-acting growth hormone (LAGH), offering once-weekly dosing as an alternative to daily injections.

Benke explained navigating the insurance approval process was another challenge.

“Our insurance required us to try a daily medication before approving a weekly option,” she said.

Alex spent three months on daily medication, often missing doses, before he was approved to switch to a weekly treatment option.

“The weekly option made such a positive impact,” Benke said. “We now have minimal disruptions to our daily routine and Alex hasn’t missed a single dose since.”

Beyond a more convenient dosing option, the change gave Benke peace of mind.

“We could focus more on being a family again, without the daily worries of his next dose,” she said.

If you’re concerned about your child’s growth, talk to their doctor as soon as possible. Early diagnosis is important, as treatment becomes less effective once a child’s bones stop growing.

Benke’s advice to other parents: “Trust your instincts. If something feels wrong, seek out a specialist and push for answers and don’t give up, even when faced with hurdles… Stay hopeful and persistent – it’s a journey worth fighting for.”

Visit GHDinKids.com to download a doctor discussion guide to help prepare for your next appointment.

SOURCE:

Skytrofa

Discover more from Daily News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Lifestyle

How to reduce gift-giving stress with your kids – a child psychologist’s tips for making magic and avoiding tears

Reduce gift-giving stress with kids: A child psychologist shares practical rules for stress-free gift giving with kids—how many gifts to give, what holds attention, and how to avoid holiday tears.

Last Updated on January 9, 2026 by Daily News Staff

Dive into “The Knowledge,” where curiosity meets clarity. This playlist, in collaboration with STMDailyNews.com, is designed for viewers who value historical accuracy and insightful learning. Our short videos, ranging from 30 seconds to a minute and a half, make complex subjects easy to grasp in no time. Covering everything from historical events to contemporary processes and entertainment, “The Knowledge” bridges the past with the present. In a world where information is abundant yet often misused, our series aims to guide you through the noise, preserving vital knowledge and truths that shape our lives today. Perfect for curious minds eager to discover the ‘why’ and ‘how’ of everything around us. Subscribe and join in as we explore the facts that matter. https://stmdailynews.com/the-knowledge/

Discover more from Daily News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

health and wellness

Texas cities have some of the highest preterm birth rates in the US, highlighting maternal health crisis nationwide

Texas cities have some of the highest preterm birth rates in the US, highlighting maternal health crisis nationwide

Revealing disparities that drive preterm birth rates

The March of Dimes report scored the U.S. overall a D+ grade on preterm birth rate at 10.4%, but states differ dramatically in their scores. New Hampshire, for example, scored an A- with 7.9% of infants born prematurely, while Mississippi, where 15% of infants are born prematurely, scored an F. Texas’ rates aren’t the worst in the country, but it scores notably worse than the national rate of 10.4%, with 11.1% of babies – 43,344 in total – born prematurely in 2024. And Texas has an especially large effect on the low national score because 10 of the 46 cities that receive a D or F grade – defined in the report as a rate higher than the national rate of 10.4% – are located there. In 2023, Texas had the highest number of such cities in the U.S. That may be in part because access to maternal care in Texas is so limited. Close to half of all counties across the state completely lack access to maternity care providers and birthing facilities, compared with one-third of counties across the U.S. Moreover, more counties in Texas are designated as health professional shortage areas, meaning they lack enough doctors for the number of people living in these areas. Shortages exist in 257 areas in Texas for primary care doctors, 149 for dentists and 251 for mental health providers. But even against the backdrop of geographic differences in health care access, the starkest contribution to the state’s preterm birth rates comes from ethnic and racial disparities. Mothers of non-Hispanic Black (14.7%), American Indian/Alaskan Native (12.5%), Pacific Islander (12.3%) and Hispanic (10.1%) descent have babies prematurely much more often than do mothers who are non-Hispanic white (9.5%) or Asian (9.1%). These numbers reflect the broader landscape of maternal health in the U.S. Although nationwide maternal mortality rates decreased from 22.3 to 18.6 deaths per 100,000 live births from 2022 to 2023, Black women died during pregnancy or within one year after childbirth at almost three times the rate (50.3%) of white (14.5%), Hispanic (12.4%) and Asian (10.7%) women.

Preterm birth in context

Having a baby early is not the normal or expected outcome during pregnancy. It occurs due to complex genetic and environmental factors, which are exacerbated by inadequate prenatal care. According to the World Health Organization, women should have eight or more doctor visits during their pregnancy. Without adequate and quality prenatal care, the chances of reversing the preterm birth trends are slim. Yet in Texas, unequal access to prenatal care remains a huge cause for concern. As the March of Dimes report documents, women of color in Texas receive adequate prenatal care at vastly lower rates than do white women – a fact that holds true in several other states as well. In addition, Texas has the highest uninsured rate in the nation, with 17% of women uninsured for health coverage, compared with a national average of 8%. Nationwide, public health experts, community advocates and families are calling for comprehensive health insurance to help cover the costs of prenatal care, particularly for low-income families that primarily rely on Medicaid for childbirth. Cuts to funding for the Affordable Care Act and Medicaid outlined in the 2025 Budget Reconciliation Act make it likely that more Americans will lose access to care or see their health care costs balloon. But state-level action may help reduce access barriers. In Texas, for example, a set of laws passed in 2025 may help improve access to care before, during and after pregnancy. Texas legislators funded initiatives targeted at workforce development in rural areas – particularly for obstetrician-gynecologists, emergency physicians and nurses, women’s preventive safety net programs, and maternal safety and quality improvement initiatives. Rising rates of chronic diseases, such as hypertension, obesity and diabetes, also contribute to women giving birth prematurely. While working with the state maternal mortality and morbidity review committee, my team and I found that cardiovascular conditions contributed to the 85 pregnancy-related deaths that occurred in 2020. An upward trend in obesity, diabetes and hypertension before pregnancy are pressing issues in the state, posing a serious threat to fetal and maternal health.Learning from other countries

These statistics are grim. But proven strategies to reduce these and other causes of maternal mortality and morbidity are available. In Australia, for instance, maternal deaths have significantly declined from 12.7 per 100,000 live births in the early 1970s to 5.3 per 100,000 between 2021 and 2022. The reduction can be linked to several medical interventions that are based on equitable, safe, woman-centered and evidence-based maternal health services. In Texas, some of my colleagues at Texas A&M University use an equitable, woman-centered approach to develop culturally competent care centered on educational health promotion, preventive health care and community services. Utilizing nurses and nonmedical support roles such as community health workers and doulas, my colleagues’ initiatives complement existing state efforts and close critical gaps in health care access for rural and low-income Texas families. Across the country, researchers are using similar models, including the use of doulas, to address the Black maternal health crisis. Research shows the use of doulas can improve access to care during pregnancy and childbirth, particularly for women of color.

It’s all hands on deck

There isn’t one, single risk factor that leads to a preterm birth, nor is there a universal approach to its prevention. Results from my work with Black mothers who had a preterm birth aligns with what other experts are saying: Addressing the maternal health crisis in the U.S. requires more than policy interventions. It involves the dismantling of system-level and policy-driven inequities that lead to high rates of preterm births and negative pregnancy and childbirth outcomes, particularly for women of color, through funding, research, policy changes and community voices. Although I had my preterm birth in Nigeria, my story and those shared by the Black mothers I have worked with in the U.S. show eerily similar underlying challenges across different settings. Kobi V. Ajayi, Research Assistant Professor of Maternal and Child Health, Texas A&M University This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.Discover more from Daily News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.