Why don’t humans have hair all over their bodies like other animals? – Murilo, age 5, Brazil

Have you ever wondered why you don’t have thick hair covering your whole body like a dog, cat or gorilla does? Humans aren’t the only mammals with sparse hair. Elephants, rhinos and naked mole rats also have very little hair. It’s true for some marine mammals, such as whales and dolphins, too. Scientists think the earliest mammals, which lived at the time of the dinosaurs, were quite hairy. But over hundreds of millions of years, a small handful of mammals, including humans, evolved to have less hair. What’s the advantage of not growing your own fur coat? I’m a biologist who studies the genes that control hairiness in mammals. Why humans and a small number of other mammals are relatively hairless is an interesting question. It all comes down to whether certain genes are turned on or off.

Hair benefits

Hair and fur have many important jobs. They keep animals warm, protect their skin from the sun and injuries and help them blend into their surroundings. They even assist animals in sensing their environment. Ever felt a tickle when something almost touches you? That’s your hair helping you detect things nearby. Humans do have hair all over their bodies, but it is generally sparser and finer than that of our hairier relatives. A notable exception is the hair on our heads, which likely serves to protect the scalp from the sun. In human adults, the thicker hair that develops under the arms and between the legs likely reduces skin friction and aids in cooling by dispersing sweat. So hair can be pretty beneficial. There must have been a strong evolutionary reason for people to lose so much of it.Why humans lost their hair

The story begins about 7 million years ago, when humans and chimpanzees took different evolutionary paths. Although scientists can’t be sure why humans became less hairy, we have some strong theories that involve sweat. Humans have far more sweat glands than chimps and other mammals do. Sweating keeps you cool. As sweat evaporates from your skin, heat energy is carried away from your body. This cooling system was likely crucial for early human ancestors, who lived in the hot African savanna. Of course, there are plenty of mammals living in hot climates right now that are covered with fur. Early humans were able to hunt those kinds of animals by tiring them out over long chases in the heat – a strategy known as persistence hunting. Humans didn’t need to be faster than the animals they hunted. They just needed to keep going until their prey got too hot and tired to flee. Being able to sweat a lot, without a thick coat of hair, made this endurance possible.Genes that control hairiness

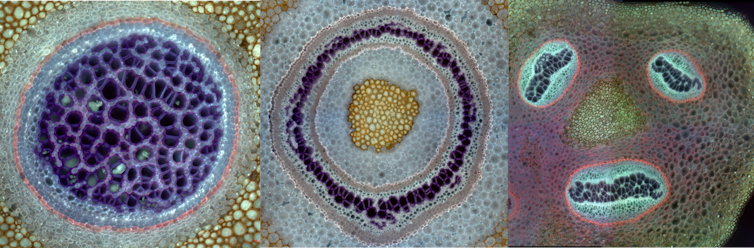

To better understand hairiness in mammals, my research team compared the genetic information of 62 different mammals, from humans to armadillos to dogs and squirrels. By lining up the DNA of all these different species, we were able to zero in on the genes linked to keeping or losing body hair. Among the many discoveries we made, we learned humans still carry all the genes needed for a full coat of hair – they are just muted or switched off. In the story of “Beauty and the Beast,” the Beast is covered in thick fur, which might seem like pure fantasy. But in real life some rare conditions can cause people to grow a lot of hair all over their bodies. This condition, called hypertrichosis, is very unusual and has been called “werewolf syndrome” because of how people who have it look.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live. And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.

The science section of our news blog STM Daily News provides readers with captivating and up-to-date information on the latest scientific discoveries, breakthroughs, and innovations across various fields. We offer engaging and accessible content, ensuring that readers with different levels of scientific knowledge can stay informed. Whether it’s exploring advancements in medicine, astronomy, technology, or environmental sciences, our science section strives to shed light on the intriguing world of scientific exploration and its profound impact on our daily lives. From thought-provoking articles to informative interviews with experts in the field, STM Daily News Science offers a harmonious blend of factual reporting, analysis, and exploration, making it a go-to source for science enthusiasts and curious minds alike. https://stmdailynews.com/category/science/