Jacob S. Suissa, CC BY-ND

Fern Stems Reveal How Evolutionary Constraints Create New Forms in Nature

Jacob S. Suissa, University of Tennessee

There are few forms of the botanical world as readily identifiable as fern leaves. These often large, lacy fronds lend themselves nicely to watercolor paintings and tricep tattoos alike. Thoreau said it best: “Nature made ferns for pure leaves, to show what she could do in that line.”

But ferns are not just for art and gardens. While fern leaves are the most iconic part of their body, these plants are whole organisms, with stems and roots that are often underground or creeping along the soil surface. With over 400 million years of evolutionary history, ferns can teach us a lot about how the diversity of planet Earth came to be. Specifically, examining their inner anatomy can reveal some of the intricacies of evolution.

Sums of parts or an integrated whole?

When one structure cannot change without altering the other, researchers consider them constrained by each other. In biology, this linkage between traits is called a developmental constraint. It explains the limits of what possible forms organisms can take. For instance, why there aren’t square trees or mammals with wheels.

However, constraint does not always limit form. In my recently published research, I examined the fern vascular system to highlight how changes in one part of the organism can lead to changes in another, which can generate new forms.

Jacob S. Suissa, CC BY-ND

Before Charles Darwin proposed his theory of evolution by natural selection, many scientists believed in creationism – the idea that all living things were created by a god. Among these believers was the 19th-century naturalist Georges Cuvier, who is lauded as the father of paleontology. His argument against evolution was not exclusively based in faith but on a theory he called the correlation of parts.

Cuvier proposed that because each part of an organism is developmentally linked to every other part, changes in one part would result in changes to another. With this theory, he argued that a single tooth or bone could be used to reconstruct an entire organism.

He used this theory to make a larger claim: If organisms are truly integrated wholes and not merely sums of individual parts, how could evolution fashion specific traits? Since changes in one part of an organism would necessitate changes in others, he argued, small modifications would require restructuring every other part. If the individual parts of an organism are all fully integrated, evolution of particular traits could not proceed.

However, not all of the parts of an organism are tethered together so tightly. Indeed, some parts can evolve at different rates and under different selection pressures. This idea was solidified as the concept of quasi-independence in the 1970s by evolutionary biologist Richard Lewontin. The idea of organisms as collections of individually evolving parts remains today, influencing how researchers and students think about evolution.

Fern vasculature and the process of evolution

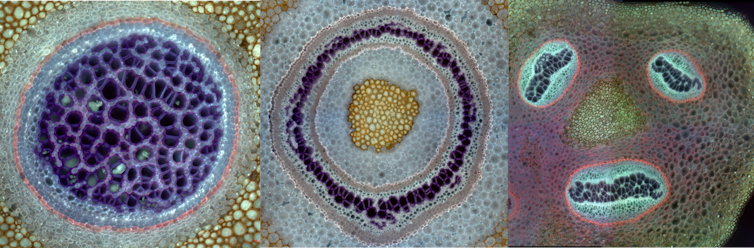

Ferns are one of four lineages of land plants that have vascular tissues – specialized sets of tubes that move water and nutrients through their bodies. These tissues are composed of vascular bundles – clusters of cells that conduct water through the stem.

How vascular bundles are arranged in fern stems varies substantially. Some have as many as three to eight or more vascular bundles scattered throughout their stem. Some are arranged symmetrically, while others such as the tobacco fern – Mickelia nicotianifolia – have bundles arranged in a whimsical, smiley-face pattern.

Jacob S. Suissa, CC BY-ND

For much of the 20th century, scientists studying the pattern and arrangement of vascular bundles in fern stems thought these broad patterns may be adaptive to environmental conditions. I set out in my own research to test whether certain types of arrangements were more resistant to drought. But contrary to my initial hypotheses – and my desire for a relationship between form and function – the arrangement of vascular bundles in the stem did not seem to correlate with drought tolerance.

This may sound counterintuitive, but it turns out the ability of a fern to move water through its body has more to do with the size and shape of the water-conducting cells rather than how they’re arranged as a whole in the stem. This finding is analogous to looking at road maps to understand traffic patterns. The patterning of roads on a map (how cells are arranged) may be less important in determining traffic patterns than the number and size of lanes (cell size and number).

This observation hinted at something deeper about the evolution of the vascular systems of ferns. It sent me on a journey to uncover exactly what gave rise to the varying vascular patterns of ferns.

Simple observations and insights into evolution

I wondered how this variation in the number and arrangement of vascular bundles relates to leaf placement around the stem. So I quantified this variation in vascular patterning for 27 ferns representing roughly 30% of all fern species.

I found a striking correlation between the number of rows of leaves and the number of vascular bundles within the stem. This relationship was almost 1-to-1 in some cases. For instance, if there were three rows of leaves along the stem, there were three vascular bundles in the stem.

What’s more, how leaves were arranged around the stem determined the spatial arrangement of bundles. If the leaves were arranged spirally (on all sides of the stem), the vascular bundles were arranged in a radial pattern. If the leaves were shifted to the dorsal side of the stem, the smiley-face pattern emerged.

Importantly, based on our understanding of plant development, there was a directionality here. Specifically, the placement of leaves determines the arrangement of bundles, not the other way around.

Jacob S. Suissa, CC BY-ND

This may not sound all that surprising – it seems logical that vasculature should link up between leaves and stems. But it runs counter to how scientists have viewed the fern vascular system for over 100 years. Many studies on fern vascular patterning have tended to focus on individual parts of the plant, removing vascular architecture from the context of the plant as a whole and viewing it as an independently evolving pattern.

However, this new work suggests that the arrangement of vascular bundles in fern stems is not able to change in isolation. Rather, like Cuvier’s idealized organisms, vascular patterning is linked to and explicitly determined by the number and placement of leaves along the stem. This is not to say that vascular patterns could not be adaptive to environmental conditions, but it means that the handle of evolutionary change in the number and arrangement of vascular bundles is likely changes to leaf number and placement.

From parochial to existential

While this study on ferns and their vascular system may seem parochial, it speaks to the broader question of how variation – the fuel of evolution – arises, and how evolution can proceed.

While not all parts of an organism are so tightly linked, considering the individual as a whole – or at least sets of parts as a unit – can help researchers better understand how, and if, observable patterns can evolve in isolation. This insight takes scientists one step closer to understanding the minutia of how evolution works to generate the immense biodiversity on Earth.

Understanding these processes is also important for industry. In agricultural settings, plant and animal breeders attempt to increase one aspect of an organism without changing another. By taking a holistic approach and understanding which parts of an organism are developmentally or genetically linked and which are more quasi-independent, breeders may be able to more effectively create organisms with desired traits.

Jacob S. Suissa, CC BY-ND

Constraint is often viewed as restricting, but it may not always be so. The Polish nuclear physicist Stanisław Ulam noted that rhymes “compel one to find the unobvious because of the necessity of finding a word which rhymes,” paradoxically acting as an “automatic mechanism of originality.” Whether from the literary rules of a haiku or the development of ferns, constraint can be a generator of form.![]()

Fern stems reveal secrets of evolution – how constraints in development can lead to new forms

Jacob S. Suissa, Assistant Professor of Plant Evolutionary Biology, University of Tennessee

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.